Framing Families in Fiction

Frank Cottrell Boyce

Traditionally in children’s fiction the adventure only gets going when the parents get lost.

I’ve always admired the dismissiveswagger with which Dahl dispatched James Trotter’s parents in James and the Giant Peach (‘killed by a rhinoceros’), and of course I love the way the father in Swallows and Amazons dismisses himself from responsibility with that telegram – ‘If not duffers won’t drown, if duffers better drowned.’ I’m mesmerised by the father in Eleanor Graham’s The Children who Lived in a Barn. When his wife is invited to speak at an international conference he says she can’t be expected to go on an aeroplane all by herself, so he and his wife leave their kids behind in rented accommodation (as it happens they’ve forgotten to pay the rent). Of course if the parents aren’t eaten by a rhinoceros or don’t abandon their children through demented sexism, then the children can always leave home to seek their fortune. Maybe they’ll get the Hogwarts letter[1], be summoned to Olympus[2], or shipwrecked on Kensuke’s island[3].

But I’m writing this in the middle of the pandemic lockdown, when most families are spending a lot more time together than they normally would. Families are often separated by absences – a parent has left, or is dead or works long hours or is away at sea. Now all of a sudden everyone is in the house. All. The. Time. Like in a hostage situation. Can you have an adventure with all the whole family? As a child reader I was always slightly wary of books that dismissed the grown-ups, because I really liked the grown-ups in my own life. If I’d met ET I would not have hidden him in my bedroom, I would have said, ‘Mum come and look at this!’ I was always suspicious of authors who pushed the idea that they somehow understood you but most grown-ups wouldn’t. It always made them sound to me a bit like those flaky uncles who turn up in Just William stories and announce that they are ‘good with boys’. ‘Who says so?’ wonders William ‘not boys I bet.’ One of the things I loved about the William stories was that his dad, his mum and siblings were all part of the cast. The same went for my favourite comic strip – The Broons.[4]

This idea that the family prevents the adventure is a relatively recent one. If you look back at fairy stories, family WAS the adventure. We can barely imagine now how grinding and dull the lives of European peasantry were. How short they were of time, food and space. How mind-bendingly tempting a house made of gingerbread would be. We often talk now as if these have complicated psychological subtexts but there’s nothing complicated or hidden about the early versions. In the early versions of Beauty and the Beast (tale type 433) the beast eats a series of failed brides.[5] In the French Mother Goose there’s a story called ‘Ma mère m’a tué, Mon père m’a mangé’ which does exactly what it says on the tin. A mother cooks her son and lets her daughter serve him to her father as a sausage. Food is not a metaphor for sex. Food is food. There is not enough of it and youngest sons and foster children can get lost or get eaten.

Victorian fiction is obsessed with money but by and large people don’t go out and earn it. They inherit it. The children in these stories often have a price on their heads because they are often the legitimate heirs, hidden away in orphanages, or lofts, adopted by apparently kindly uncles who are conniving to get them to sign everything over to them before arranging to have them – as in the case of Davey Balfour – kidnapped and sold into slavery.[6] A Series of Unfortunate Events is a brilliant modern reworking of this idea.

One book that appalled me as a child was Matilda. I still find its snobbery detestable but I can see now that the thing that upset me about it was how it seems to deny that family is relevant at all. She’s not like the bad children in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, whose flaws are the result of over-indulgent parenting. Matilda is a kind of changeling. Her parents have had no impact on her whatsoever. She speaks with a different accent from her parents. She becomes what she is despite them, and in fact to spite them. I find this interesting because Dahl also wrote the screenplay for Chitty Chitty Bang Bang which is one of the great and true family adventures, thanks in no small part to a genius creation that is all Dahl – the Child Catcher.[7] The Child Catcher is one of the most truly terrifying villains in fiction. Voldemort is just a poor misunderstood soul by comparison. Yet the Child Catcher is only on screen for a few minutes. I’ve thought long and hard about how he has so much impact. It’s because he is the public policy aspect of the weirdly perverted Bombursts. The baroness wants the baron to be her little baby so she bans real children. The Child Catcher is the weapon this creepy perversion of family life launches against the lovely wholesome family in the magical motor car. This is how all the great children’s stories work. They offer you something beautiful and enviable – a loving family with a great car, or a school that teaches you magic – and then threaten to destroy it. It’s worth remembering during these days of cancel culture that Dahl wrote two such contradictory works, that people are complicated and binary questions are useful for programming computers, not people.

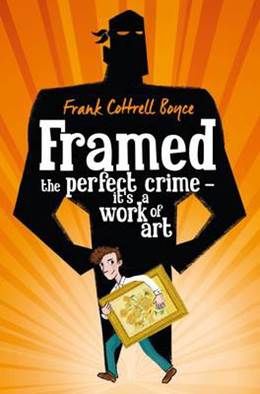

I imagine the emphasis on ditching your family that was such a strong thread in children’s writing in the 1970s was something to do with social mobility and the fact that many writers really had moved away from their families. I wonder if now that social mobility is by and large a thing of the past, and now that everyone has had this lockdown experience, the family will once again be seen as a setting for adventure. I’ve always tried to place family in the centre of my own stories partly because my family is the centre of my life and I believe in putting as much of yourself as possible into your writing. But also because I see a lot of children in schools for whom family is a troubled, complicated and sometimes dangerous place. I think one thing that children’s fiction can do powerfully is say this is how good life can be, this is what you deserve. By that I don’t mean that every parent has to be like Mrs. March faultlessly shepherding her girls through their choices and dilemmas.[8] I hope the mums and dads I’ve written are endearingly flawed as well as always loving. I think one of the things I’m most proud of writing is the moment when Dylan’s dad unwittingly drinks a mug of espresso in Framed. Because I want to say that it’s not boring to love or be loved. That’s what I took from, for instance, the brilliant Family From One End Street. I loved the Ruggles because they were, for all their differences, in it together. Family life for them was a project – a work of art – whose aim was to make the most of the little they had. The other great family for me was Tove Jansson’s Moomin family. Jansson’s picture of the family is the opposite of the one in Matilda. The Moomins’ door is always open. The ‘family’ includes a lot of frankly added and incomprehensible waifs and strays. Not everyone in the Moomin family leads the same life – Snufkin migrates for the winter while the others hibernate. Come to think of it, they’re not all the same species. Family is where tolerance is forged. Indeed if you’re inclined to make room for two tiny, double-talking ruby thieves to your table, then toleration itself will be an adventure.

One of the most powerful lines in all literature is Bobby’s cry of ‘Oh, my Daddy, my Daddy!’ at the end of The Railway Children. I don’t mean to boast but Jenny Agutter herself once left that phrase as a voicemail on my phone and I played it to everyone. It’s another one of those small moments of incredible power. It works because for the length of the book the children have been given this gift of a wild, fresh air careless childhood. Bobby loses that when she finds out the truth about her father. She’s forced to become an adult. When she sees her father emerging from the steam on the station platform, she is given back her childhood. The cry ‘Oh, my Daddy, my Daddy!’ is the cry of someone forced to have grown up, becoming a child again. That’s what the best children’s writing does for all of us. It gives us a chance to be as little children once again.

Notes

1 Letter of acceptance to the Hogwarts school of witchcraft and wizardry in J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (illus. Thomas Taylor) (1997), London: Bloomsbury.

2 Rick Riordan’s the Percy Jackson series.

3 A boy Michael is shipwrecked on an island in Michael Morpurgo’s Kensuke’s Kingdom (illus. Michael Foreman) (1999), London: Egmont.

4 The Broons. A cartoon strip published by DC Thomson Media. https://www.dctmedia.co.uk/brands/the-broons/.

5 Type 433. See Aarne–Thompson–Uther Index. http://oaks.nvg.org/folktale-types.html#300.

6 David Balfour is the main character in Robert Louis Stevenson’s Kidnapped (1886), London: Cassell & Co,

7 Chitty Chitty Bang Bang. Film (1968), screenplay by Roald Dahl, based on the book Chitty Chitty Bang Bang: The Magical Car (London: Jonathan Cape, 1964) by Ian Fleming.

8 Mrs March, called Marmee by her four daughters in Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women (1860), Boston, MA: Roberts Brothers.

Works cited

Boyce, Frank Cottrell (2008) Framed. London: Macmillan Children’s Books.

Crompton, Richmal (illus. Thomas Henry) (1922) Just William. London: George Newnes.

Dahl, Roald (illus. Jacques Faith) (1964) Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Dahl, Roald (illus. Nancy Ekholm Burkert) (1961) James and the Giant Peach. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Dahl, Roald (illus. Quentin Blake) (1967) Matilda. London: Jonathan Cape.

Garnet, Eve (illus. Eve Garnett) (1937) The Family from One End Street. London: Frederick Muller.

Graham, Eleanor (1938) The Children who Lived in a Barn. London: G. Routledge & Sons.

Jansson, Tove (illus. Tove Jansson) (trans. Elizabeth Portch) (1950) Finn Family Moomintroll. London: Ernest Benn.

Nesbit, E. (illus. C.E. Brock) (1906) The Railway Children. London: Wells Gardener & Co.

Ransome, Arthur (cover illus. Steven Spurrier) (1930) Swallows and Amazons. London: Jonathan Cape.

Snicket, Lemony (illus. Brett Helquist) (2006) A Series of Unfortunate Events. London: Egmont.

Villeneuve, Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot de Gallon de (1740) Beauty and the Beast (La Belle et la Bête). Published in La Jeune Américaine, et les Contes Marins.

Frank Cottrell Boyce is the award-winning author of Millions, Sputnik’s Guide to Life on Earth, Runaway Robot, Framed, Cosmic, The Astounding Broccoli Boy and the Chitty Chitty Bang Bang sequels. Frank Cottrell Boyce’s first book, Millions, won the CILIP Carnegie Medal in 2004 and he also won the Guardian Children’s Fiction Prize for The Unforgettable Coat (Walker Books). Frank Cottrell Boyce is a highly successful British screenwriter whose credits include The Railway Man, Millions and Goodbye Christopher Robin. He is also a judge for the BBC Radio 2 500 Words competition. He resides in Merseyside with his family.

Instagram: @frank_cottrell_boyce Twitter: @frankcottrell_b.