Summer 2020

Issue 58

Families in Children’s Literature: It Takes All Sorts

![]()

Families in Children’s Literature: It Takes All Sorts

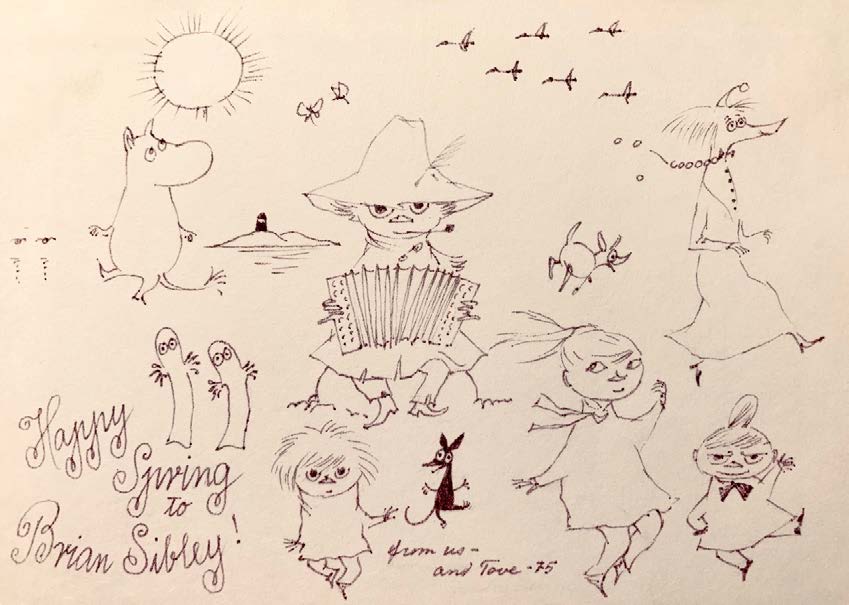

It is perhaps a truism that you can always choose your friends – but not your family. Luckily most families, while they may have moments of trauma or difference, are on the whole the most important group in your life and relationships are happy or at least tolerant of idiosyncrasies. How do families fare when in the hands (or under the pen) of an author? If current young adult books are to be believed, dysfunction is the norm – or seems to be. However, there are other more positive depictions as Brian Sibley records in his homage to the Moomin family. Frank Cottrell Boyce however looks back with a certain pleasurable frisson to the many varied – and sometimes downright – strange families to be met in books for children. There is surely nothing cosy about the parents in the French tale ‘Ma mère m’a tué, Mon père m’a mangé’! Here is a real contrast to the comforting presence of Moominmamma for whom no addition to the family home is too much and who can always be relied on to rise to the occasion. Moominpappa is, of course, a rather different proposition. But that is what makes a family interesting and memorable because the reader can recognise elements from their own experience.

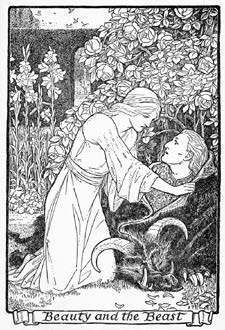

Or can they? Patrice Lawrence reminds us that for her growing up, this was far from the case. Though the unit – and perhaps the relationships, might have struck a chord, they did not portray her family since the only books she saw reflected an exclusively white British society. Where were the diverse families she knew through her lived experience? It has taken a long time for this to change and it is still a long way from a norm where all children will be able to find themselves and their families as well as others in the books they read. Patrice Lawrence, of course, is very much in the vanguard of this movement.

The Moomins are, it is true, not human. Nor are the Mennyms; they are a family of life–size rag dolls who, through the imagination of the author Sylvia Waugh, are living their lives quite happily (or not) among their human neighbours; Joshua indeed has a job as a night watchman for Sydenham’s Electrical Warehouse. Susan Bailes introduces us to this meticulously crafted series that charts the fortunes of the Mennym family, the tensions, the joys, the woes, the successes, failures, hopes and ambitions. Under the pen of the writer their characters step off the page to become a family that could be living next door, quietly and unobtrusively. It is extraordinary that they seem to have slipped into the shadowy limbo – though living in the shadows was always an important part of their existence.

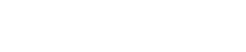

But what about real human families? There are plenty of celebrated literary families – the Farjeons, or the Brontes for example. Then there are the Gattys. This extraordinary family is brought to our attention by Sarah Jardine-Willoughby. It was not just the matriarch Margaret Gatty who was talented – she not only wrote for children to support the family but was also an expert on seaweeds – her ten children also wrote stories and poems, composed, drew – or even painted. They all contributed to Aunt Judy’s magazine which ran from 1866 to 1885, at one time or another. It was created by Margaret and named after her second daughter, Juliana, who became its editor and a major contributor for almost the whole of its existence.

Families . . ., it takes all sorts!

Ferelith Hordon

The Gatty Family – Close and Talented

An exploration of the Gatty family by Sarah Jardine-Willoughby.

The Mennym Family

A study of the Mennym family by Susan Bailes.

Framing Families in Fiction

Frank Cottrell Boyce examines how families are represented in children’s fiction.

From a Mountain to a Rocket: Diversity and Family Representation in Children’s Books in the UK

Patrice Lawrence discusses the issue of diversity in children’s books, drawing on her own personal experience.

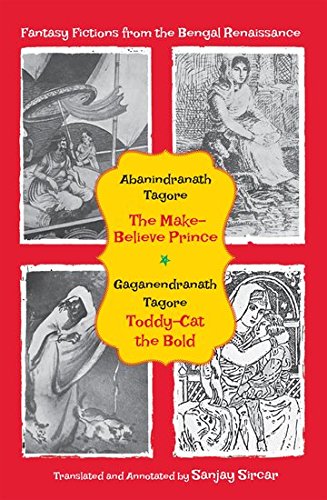

Book Review: Fantasy Fictions from the Bengali Renaissance

Pat Pinsent reviews Fantasy Fictions From The Bengal Renaissance

My Family – The Moomins

Brian Sibley discusses his love of the Moomins.