Wandering in the Landscape of Magical Reality – Exploring David Almond’s Archive

Elizabeth Byrne

David Almond is the renowned author of fiction for children and young adults, including Skellig (1998), Kit’s Wilderness (1999), The Fire-Eaters (2003), The Savage (2008), My Name is Mina (2010), A Song for Ella Grey (2014) and most recently The Colour of the Sun (2018).

In his writing for children Almond explores the extraordinary that exists within the seemingly ordinary, the wondrous and strange possibilities in the everyday. His strange, lyrical and fantastical stories are earthed in the North East, in the landscape, nature and language of his childhood – both real and reimagined – especially his home town of Felling in Gateshead. But his explorations of this landscape take place in a hinterland somewhere between its physical geography, remembered by an adult recalling hours of childhood wandering, and the dreams and imaginings of childhood.

The north-east that I write about is a real north-east, I could take you to the places, but it was also like a fictional north-east that has been kind of reimagined so that it works inside stories. It seems to me now what I’m doing is kind of taking that wandering that I did as a child, and it’s almost like the page becomes a place in which I can wander again and wander through these landscapes and again to see them anew, to recreate them. I use the language and the pencil and pen to move through a landscape and to discover stories in it.

This knife edge between what is real and what is magical is the country of all childhood imagination, dreams, fears and creativity – for children there is only ever a porous border between the two. A shimmer of possibility illuminates his stories; turn the lump of clay in your hand this way and it is a crude figure of a man, turn it another and it appears to move and breathe with a life of its own. Steel yourself to walk down a dark tunnel that could be simply be part of a building site, or could lead to a journey to the Underworld itself.

Without needing to hear from Homer’s ghost, it is evident that in writing about the North East, Almond taps into something deeply resonant to a wide range of readers – not only have his books been widely translated and earned international success, including the rare feat of both the Whitbread Children’s Award and the Carnegie Medal for Skellig (1998), a second Whitbread in 2003 for The Fire Eaters, the hugely prestigious Hans Christian Andersen Medal for writing in 2010 and the Guardian Children’s Fiction Prize for A Song for Ella Grey in 2014; they have also frequently been ‘made into something new’ in the form of plays, movies and even opera.

But when I met him in June of this year, I learned that at the very beginning of his writing career, he feared that only by rejecting his Northernness could he hope to find broader success.

When I first tried to get published some people were resistant to the fact that I was Northern, they said ‘hmm, you write in a kind of Northern working class voice and we’ve got some of those, so we don’t need you’. I thought ‘Am I going to have to kind of imagine I’m from somewhere else? Maybe there’s some kind of literary language out there somewhere, that I’ll be able to find and kind of attach to meself.’ But of course that’s nonsense, you know, your own language that is in your bones and your blood and in your history and in your memory is where your language comes from. I hope one of the things that I’ve done is to discover the kind of true poetry in what we think of as ordinary language, and to transform it into something that can be read around the world, which itis.

Almond uses language linked to earth, to blood, to clay, bones, grass, trees, birds in flight, darkness, food, water and fire; elementals rooted in the somatic, yet also made ethereal and even spiritual in his writing.

Last year Almond donated his personal archive to Seven Stories, the National Centre for Children’s Books, in Newcastle. As part of a Northern Bridge AHRC placement at Seven Stories I’ve had the opportunity to explore his archives, including manuscripts, artwork, letters from editors and the very first notebook which contains the ideas which eventually became the extraordinary Skellig.

The most profound help this has given to me in writing my first novel as part of my PhD in Creative Writing, is incoming to understand more about how Almond creates stories in which the reader is immersed in an illusionary, fantastical, yet sensate and substantial world. My own science fiction novel is about a young woman trying to find a place in which to belong and survive in a landscape catastrophically transformed by climate change, where boundaries and structures of every kind have been blurred and erased, including languageitself.

I’ve learned that one of the underpinnings of Almond’s work is the way in which he sets about the physical act of writing. He embraces mess, scrappy notes, teases out half- formed and nascent ideas across the pages of his notebooks with ideas using colour, drawings, diagrams and scribbles. These are not limited to early thoughts or draft notes – they are the building blocks of his novels right through the writing process. And he believes it is this process which allows him to tap into and rediscover the magic that lies within reality.

For me, more and more, I use colour and pictures, creating images is central to me as a writer. I use colour to help me to imagine. I think it’s a way of releasing what might be in my mind and helping me to discover what the story might be. And a lot of times when I’m doing this I’m staring into space, I’ll be chewing me pencils, I’ll be wondering, I’ll be dreaming. Central to it is this vast scribbling and it’s almost like the movement of the hand is really important; writing is a physical thing.

It seems to me now what I’m doing is kind of taking that wandering that I did as a child, and it’s almost like the page becomes a place in which I can wander again and wander through these landscapes and again to see them anew, to recreate them. I use the language and the pencil and pen to move through a landscape and to discover stories in it.

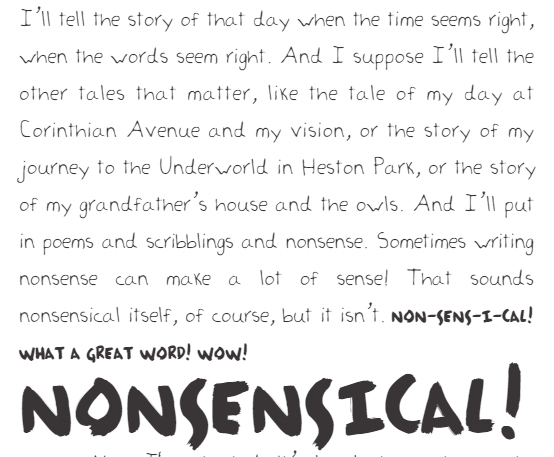

This is echoed and amplified in the physical format of the book itself, which uses many different fonts and formats to convey Mina’s ideas, and her emotional state. It plays with white space on the pages and experiments with a variety of styles. It is, in fact, the finished book which most explicitly resembles one of Almond’s own notebooks. And Mina is perhaps the character who most closely resembles Almond, or at least the part of Almond who always inhabits those borderlands between.

Writing will be like a journey, every word a footstep that takes me further into an undiscovered land. (My Name is Mina, p.16, Hodder Children’s Books 2010)

Cited works of David Almond

(1998) Skellig. London: Hodder Children’s Books.

(1999) Kit’s Wilderness. London: Hodder & Stoughton.

(2003) The Fire Eaters. London: Hodder Children’s Books.

(illus. David McKean) (2008) The Savage. London: Walker Books.

(2010) My Name is Mina. London: Hodder Children’s Books.

(illus. Karen Radford) (2014) A Song for Ella Grey. London: Hodder Children’s Books.

(2018) The Colour of Sun. London: Hodder Children’s Books.