Two Great People I Met along the Way: Two Stories of Publishing in the 80s

Jon Agee

My publishing life began in 1981 with Frances Foster. She was my editor – my first editor ever! – at Pantheon Books, in the sleek Random House building on 50th Street in New York City.

Frances was an angel, that is, when I think of her I’m reminded of her gentle spirit, which I associate with an angel. But, not to be fooled, she was bright and clever, and she had a droll sense of humour. These qualities just happened to be hidden by a layer of reserve or modesty, or maybe it was just some deeper wisdom.

When I first walked into Frances’ office, I was an inexperienced, overconfident, uninformed, insecure, recent college grad. All I knew was that a standard children’s picture book was 32 pages, and that Frances published the great Leo Lionni. Frances took my youthful energies in stride. She was an ideal editor; genuinely supportive, and able to instruct or share her point of view in ways that almost seemed deferential.

She would go on to publish my first two books, the first of what I thought might be many, many more, until the day I brought her the dummy for a new book idea, titled Ludlow Laughs.

Ludlow was the story of a grump, born with a perpetual scowl. He grumbles off to work each day, conveniently enough, at a Complaint Department. One night, Ludlow has a dream which causes him to laugh in his sleep. His laughter, it turns out, is as contagious as our global pandemic. It travels all over the world – until the sleeping Ludlow wakes up in the morning, opens his window, and tells everybody to ‘Shaddupp!’, before grumbling off to work.

Frances looked at it and seemed amused, and then asked for some time to look at it more closely. Weeks passed. Then, one day, on a visit to her office, she told me that the artist Leonard Baskin had recently stopped by. He was illustrating a book for her, and apparently, he’d seen the dummy for Ludlow Laughs on her desk, and asked to look at it. ‘He absolutely loved it,’ said Frances. It was very generous of her to tell me this story, particularly because, as it turns out, she didn’t feel the same way as Baskin. Her feeling – she finally expressed it! – was that the subject matter and the humour were too grown-up for kids. Frances didn’t expect me to agree, nor did she expect me to let the dummy gather dust in a drawer. In fact, she knew that I’d take it to another publisher, and that, very likely, it would be published. And she was right.

Stephen Roxburgh, the children’s editor at Farrar, Straus, Giroux, was charmed by Ludlow, and agreed to publish it. I was delighted, naturally, but what I learned, is that moving to another publisher is not a one-book affair. This business model may have changed today, but in 1984, if a publisher was committed to an author, the author was expected to remain loyal to a publisher. Stephen was certainly committed to me, and I would go on to do many books with him. Alas, my relationship with lovely Frances Foster, was over.

••••••••••

In the 1980s – in the United States – a lot of children’s picture books were printed and bound just across the river from New York City, in New Jersey, at the Horowitz/Rae Company. Because of its proximity to publishers, it was not uncommon for authors, like me, to accompany a production manager and oversee the printing of the book.

We would arrive in the morning. A company rep would lead us through the factory, past the enormous, noisy printing presses, to a quiet, sealed-off room. There, we’d relax, sip coffee, and wait for the press manager to bring – directly off the press – the first good printed sheets. Using the original art, we would try and match up the colours.

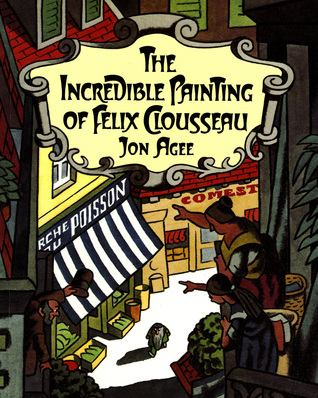

One morning, as we stepped into the room, the press sheet of my fourth book, The Incredible Painting of Felix Clousseau, along with the original art, was already laid out on the table. The pressman was there, chatting with another production manager. There was also a third person, leaning over the table, examining my art. It was Maurice Sendak.

Maurice had come to check on the printing of a poster. His book, Dear Mili, had been published earlier in the year – to his customary acclaim – and soon the art would be displayed at the Pierpont Morgan Library. Introductions were made, and Maurice, in his brusque New York tone, said: ‘I love your art. So, why have I never heard of you?’

I explained that I’d stumbled into publishing seven years earlier, just out of college. My first three picture books had received very little notice. In fact, my third book – Ludlow – had such poor early sales that my publisher – Stephen Roxburgh – quickly managed to shift the printing to paperback.

Maurice turned back to Felix Clousseau. ‘So,’ he said, ‘you must be a fan of André Hellé!’. I’d never heard of him. ‘How about Edy Legrand?’ I hadn’t heard of him either.

A couple of weeks later, I drove up to Maurice’s place in Connecticut for lunch. He’d invited me expressly to show off his vast picture-book collection, which included rare editions of LeGrand and Hellé, among other great early twentieth-century book illustrators. When I arrived, he was in a good mood. He’d just finished watching his favourite daytime soap opera.

While his assistant Lynn got lunch ready, he took me on a tour of his sprawling stone cottage. The place was like a museum. From a shelf, among several antiques, he pulled down an object that looked like a thick, old leather wallet. He opened it up to reveal delicate pages of tiny, densely printed text. It was one of the earliest editions of Grimms’ Fairy Tales. Next to it was Beatrix Potter’s original pen-and ink-case (with pen and inkwell inside). Next to that, on the wall, was a drawing of Babar, by Jean du Brunhoff. Every room seemed to be cluttered with treasures from his boundless Mickey Mouse collection – dolls, tin toys, puzzles, games.

Recently, Maurice had become obsessed with antique wind-up music boxes. He had been searching specifically for something from eighteenth-century Vienna. Since most of them existed in museums, he’d located, in Germany, a luthier, who made music boxes that perfectly mimicked the originals. He took one off the shelf and wound it up. ‘Listen to that,’ he said as the tinny music played. ‘It’s exactly what Mozart must have heard when he was a child!’.

Adjacent to his house, was a small climate-controlled cottage devoted to his larger illustrated book collection. Bookcases stacked with hundreds of picture books lined the walls. Larger books were stored in file cabinets, lying flat to protect their bindings. We leafed through first editions of Hellé and LeGrand, and I was able to see the connection to Felix Clousseau: bold shapes, strong lines, saturated colour. He showed me a beautiful, over-sized book illustrated with lithographs by Ferdinand Leger. Maurice had bought most of these from rare-book dealers, paying for some of the pricier ones in instalments, long before he’d made any money in publishing. It was clear that he was not just a book creator. He was a voracious, expert book collector.

We had lunch, and he asked about Felix Clousseau. If I wasn’t influenced by Hellé or LeGrand, what were my sources? ‘You, for one,’ I replied. ‘And Tomi Ungerer, Leo Lionni, Peter Arno, Ludwig Bemelmans’. And a relatively obscure Belgian cartoonist named Edgar P. Jacobs. I was also spending time at the New York Public Library, sketching from photographs of turn-of-the-century Paris: pictures by Atget, Lartrigue, Brassai.

Felix Clousseau was an odyssey. As I worked on it, I moved four times, from one borough of New York City to another. Luckily, in the mid 80’s, it was still possible to thrive with not much income. My parents, however – like good, concerned parents – worried about how long the book was taking. My publisher, Stephen, was more patient. He assured me that I would finish it ‘all in the fullness of time’. He might have regretted that statement. It took three years before I did.

Maurice understood. He’d had his share of epic book projects. He also knew how, in the end, when you put the last brush stroke to the final picture of a book, there is no applause – nothing. There’s just you, alone in your studio, and maybe your dog, wondering if you’re going to take him out for a walk.

Fittingly, as the afternoon wound down, we took his dog out for a walk, through the woods near his house. When it came time to go, Maurice walked me to the front door and threw out his arms: big hug. We were from different generations, and upbringings, with very different temperaments, but we genuinely hit it off.

Several months later, The Incredible Painting of Felix Clousseau was published, and I sent Maurice a copy. He called me. He was over the moon. ‘It should win the Caldecott Medal!’. Then he paused and said: ‘Well, to be honest, I want Dear Mili to win, but if it doesn’t, I hope it’s Felix’. I couldn’t argue with that.

For the next decade or so, we’d see each other every year, in Connecticut or New York City or at a book event on the east coast. Then I moved to California and my visits were less frequent. In the fall of 2011, he called me and said that I should think about visiting him before he ‘kicked the bucket’. That winter, my wife and I flew back to New York and drove up to see him. He was frail, and less agile, but his mind and spirit were still in great form, he was full of wit and wisdom. In fact, almost in anticipation of his imminent demise, he’d recently given a triumphant interview on radio (Fresh Air) and another on TV with Steven Colbert. Maurice was ready to die, he said, but he was also going to miss life terribly. The following spring he passed away. I miss him terribly, too.

Works cited

Grimm, Wilhelm (illus. Maurice Sendak) (2004) Dear Mili. New York: Michael Di Capua Books.

The following books are by Jon Agee.

(1985) Ludlow Laughs. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

(1988) The Incredible Painting of Felix Clousseau. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

(1991) Go Hang a Salami! I’m a Lasagna Hog! and Other Palindromes. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

(1994) I’m a Lasagna Hog, and Other Palindromes. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux. (First published in 1991 by Trumpet Club.)

(2017) Life on Mars. New York: Dial Books.

(2018) The Wall in the Middle of the Book. New York: Dial Books.

Jon Agee is the author and illustrator of many acclaimed books for children, including, The Wall in the Middle of the Book, Life on Mars and The Incredible Painting of Felix Clousseau. He is also the creator of many books of wordplay, most notably Go Hang a Salami! I’m a Lasagna Hog, and Other Palindromes. He lives in California.