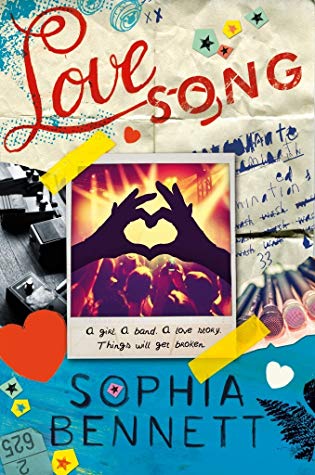

On Music – The Making of Love Song

Sophia Bennett

I am listening to Led Zeppelin with my seven-year-old son. Thanks to an earlier book about a girl band, I have taken up bass guitar and am trying to find new songs for my playlist.

In the way of these things, one track to another, and we go down a musical rabbit hole until, in the gathering darkness of the early evening a stand-out guitar riff pulls us both in . . . and we look at each other and know we’ll always have this moment.

The track is ‘Kashmir’. I know its iconic da-da-dah, da-da-dah opening chord sequence by osmosis, but could not have named the song. This evening, in the dying light, my son and I get lost in its poetic sense of mystery; the ethereal wail of Robert Plant suggests infinite adventures in far-off lands. We are bonded by this strange experience of music from a time when I was little, decades before he was born.

Later, I’ll write the moment in Love Song. Same track, same sense of discovery. But not for a mother and son this time: for a girl and a bad boy rock star. Of course, I amped it up to 11. There is a storm outside. They are almost alone in a huge, crumbling house in Northumberland. He is one of the most famous musicians on the planet. In honour of Public Image Ltd, the title of the book was originally going to be This Is Not a Love Song – and it isn’t a proper love story, really. The boy and girl may well not end up together. But it’s a true love letter to music, and what it can do to you.

In around 2014 I set out to write a book about the dying days of the pop boy band One Direction. Much of my readership was obsessed, and when it came to Harry Styles I could perfectly understand why. But I watched those boys on tour after tour and thought how very exhausted they must be; how they must long to step out of the limelight for a while; how the joy of seeing new cities must have palled. That was the band I wanted to explore – the one the fans never get to see.

Researching Love Song was a series of pinch-me moments. The idea came from a boy band, but the more I researched the more I was inspired by the groups from my early days who were experiencing the madness for the first time in history: the Beatles, the Rolling Stones and later, Duran Duran.

I devoured Hunter Davies’s account of the Beatles’ rocket-speed ascent to fame, when they let him travel along like a fifth member of the band (1968). I could legitimately and tax-deductably lie on the sofa reading John Taylor’s entertaining autobiography In the Pleasure Groove (2013), about being a worldwide sex symbol in the 1980s. The crowd at Madison Square Garden in Love Song – like pixels on a massive screen – is based entirely on Taylor’s account. So is one of the characters, and if you know him you probably won’t find it too hard to guess who.

My father was, and is, a Rolling Stones fan. One of the high points of his life was getting to hang out with the band after a concert in Berlin. I devoured Keith Richards’ autobiography Life (2010), which is just as geeky about reel-to-reel recording and open-chord tuning as it is about how and where to find high quality heroin on the road. (He approached it with the care and precision of a professional chemist, and that is possibly why he’s still alive.)

For many years the Rolling Stones used a recording bus they’d had built for them, which they could park outside whichever mansion they happened to be writing songs in. Known as Rolling Stones Mobile Studio, it looked like a Portakabin on wheels, but inside it was magic. Sticky Fingers (1971) was largely mixed here and it was later used by bands from Led Zeppelin to Queen and Patti Smith. It’s immortalised in Deep Purple’s ‘Smoke on the Water’ (1972) – the song with perhaps the most iconic guitar riff of all time – because they were using it to record their album Machine Head (1972) in Switzerland, and it was rescued just in time from a nearby fire.

In real life, the bus lives in retirement in Canada, but in fiction it came back for one last hurrah in Love Song, and was parked outside Heatherwick Hall for the benefit of The Point. I like to think that Windy, the band’s eccentric manager, would have had it flown over at reckless rock expense for the boys.

The Hall is inspired partly by Headley Grange in Hampshire, where Led Zeppelin recorded ‘Kashmir’. Knowing I was writing the book, Barry Cunningham, my publisher (who has a 1970s rock history of his own) gave me Hammer of the Gods (1985), the unauthorised biography by Stephen Davis. The madness of their tours in the US was fascinating. A couple of lines about The Point’s early days, driving through snowstorms to make gigs where five people showed up, pay homage to their beginnings. But just as beguiling is the account of their friendly, laid-back recording days, living like hippie country gents in the English countryside (apart from John Bonham, the drummer, who spent much of the time in an alcoholic stupor) and creating songs that would become the soundtrack to a generation.

Love Song is infused with music. There’s a playlist at the back, with a QR code that links to Spotify, so readers can listen as they go along. It references the Beatles, the Cure, Blondie, Muddy Waters, Jimi Hendrix, David Bowie, Mark Ronson and many more. There was a worry that a teenage audience wouldn’t identify with ‘old’ music – but teenage audiences today are the most music-literate we’ve ever had. Thanks to internet streaming they have access to most of the music in the world, and teenagers are curious. They click on links and make connections. They discover a vintage riff they love and sample it and share. They make no music hierarchy; they know it’s personal. This makes writing about life-changing music for them a joy.

However, when you write about music you quickly learn that though you can quote from books in satisfying chunks, you cannot safely quote from a song, however much you long to share what its lyrics mean to you. Not unless you want to pay a fortune. Instead, I had to write my own. It’s a totally different mental process from writing a story, or even pure poetry. I became fascinated by songwriters from Paul McCartney to David Bowie and Leonard Cohen talking about jotting down iconic lyrics on a napkin, or an envelope. That’s all it takes: inspiration and a handy pen.

Then comes the chemical experiment by the band to create a mood and sound and a hook. All those rock biographies captured the joy in the early days of jointly creating something iconic, followed by the fallings out, the rivalries and recriminations. If you want to write young adult literature all the highs and lows are there. Just add some misplaced desire and wait for fireworks to happen.

It was that chemistry that caught me in the end. Being in a band is ultimately about enduring creative friendship – one that often starts in early adolescence and has to survive whatever comes next. No wonder it goes wrong so often. But I can’t think of anything more fascinating and wonderful while it lasts. And sexy. It wasn’t sleekly styled boys staring out at the cameras I wanted to see, it was young men fresh from sleep, stuck in a crummy room together, using each other’s ideas and some old-fashioned technology to make something that filled them with wonder and joy. From silence and frustration, those opening chords that build to a song that will become the soundtrack to a million lives.

In my book, my girl and her boys break up, make up, listen to some of the greatest pop and rock of the late twentieth century, and go on to create their own. I was astonished when – as a young adult novel – Love Song won the Romantic Novel of the Year in 2017. I’m pretty sure it was the music scenes that did it.

Oh, and my husband plays and makes guitars. Not sure that’s obvious from the way I write about music and love, and the boys in the band. But possibly.

Works cited

Bennett, Sophia (2016) Love Song. Frome: Chicken House Books.

Davies, Hunter (1968) The Beatles: The Authorised Biography. London: Ebury Press.

Davis, Stephen (1985) Hammer of the Gods. New York: William Morrow and Co.

Richards, Keith (2010) Life. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Taylor, John (2013) In the Pleasure Groove: Love, Death, and Duran Duran. London: Random House.

Sophia Bennett is the author of Threads (2015), The Look (2016), Love Song (2016) and several other books for teens. The Times has called her ‘the queen of teen dreams’. Her latest book, The Bigger Picture: Women Who Changed the Art World (2019) is an illustrated guide to great women artists, old and new, with works in the Tate’s collection. Sophia teaches Writing for Children at City University.