‘Old’ Ladies in New Spaces: Cinderella and Little Red in Modern Cities

Dalila Forni

Roberto Innocenti is an Italian self-taught artist who has gained worldwide success illustrating many classic fairy tales and adapting them to his peculiar style. The artist often chooses to set his illustrations in contemporary times: ‘For Innocenti, magic and mystery do not belong to a far-away realm but rather form an integral part of the world in which we live’ (Myers, 2008).

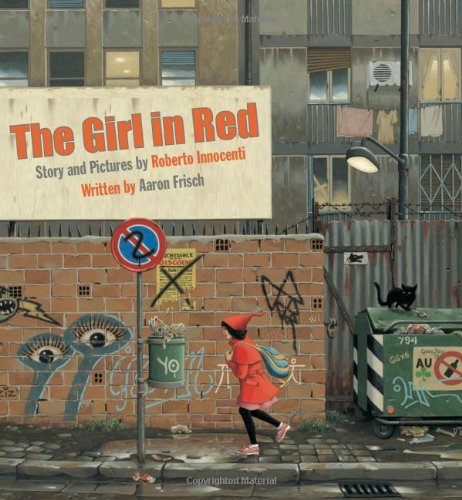

The Girl in Red with text by Aaron Frisch (2012) is a contemporary retelling of Perrault’s ‘Little Red Riding Hood’. Marshall (2015: 163) defines it a ‘fusion text’, that is, a text with characteristics from the graphic novel, the comic and the picture book. Indeed, the format of the work clearly goes back to the picture book, but the panels structured by the artist are typical of the comic.

Sophia, the protagonist, is a young girl who lives with her single mother and her little sister in a bleak, high-rise building. The interior of her flat is colourful and apparently safe: the kitchen – the only room depicted – is furnished with a small table, a cupboard with cartoon-like stickers, a fridge decorated with some flowers and a TV where some cartoons are broadcast. Sophia leaves her home to visit her sick grandmother. Her mother warns her that she should be careful.

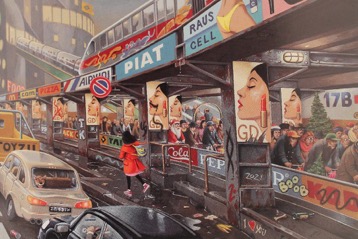

In Innocenti’s version of the fairy tale, the forest is turned into a contemporary city, possibly New York, while the wood is replaced by a shopping mall called ‘Il bosco’ [The wood]. Thus, Sophia walks through a crowded and dirty city in order to reach her granny’s house and bring her some food. Although the little girl is the main character of the story, it is usually difficult to detect her in the wide and hyper-realistic city represented by Innocenti. The girl is often walking in the streets, lost in a huge crowd or hidden in a wall full of graffiti. This particular choice creates an interesting ‘Where’s Waldo?’ effect (Marshall and Gilmor, 2015: 99). As Sophia penetrates in the depths of the city, she becomes smaller and smaller in an urban space that gobbles her up in its filthy and threatening streets. The reader can clearly perceive her vulnerability and disorientation: Sophia is absorbed in a dangerous world and misses the right way, the path she had to follow to stay out ofdanger.

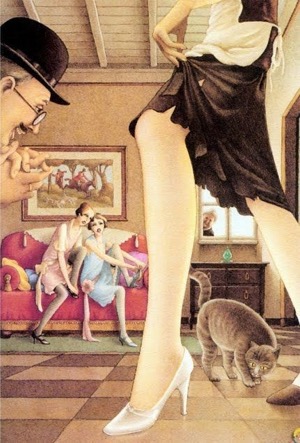

What is interesting about the new setting depicted by Innocenti is the continual reference to adulthood. The artist provides the reader (and viewer) a ‘sexed-up imagery of adult entertainment districts’ (Marshall and Gilmore, 2015). As Sophia gets smaller and smaller, sexual overtones – such as hypersexualised girls, fragmented parts of female bodies and risqué advertisements – get more and more prominent. For instance, the walls are covered by images where lips, feet in high heels, female bottoms and underwear are clearly represented. Innocenti captures a (soft) ‘pornosphere’ or ‘striptease culture’ (McNair, 2002: 81) that is now extremely common in our streetscapes. Thus, the artist depicts Western society in an apparently old fairy tale: the woods are now chaotic cities and contemporary dangers are hidden in misogynist and hypersexualised posters, usually visible to children and influential in their perception of gender identity. As argued by Leena-Maija Rossi (2007): ‘Images do not function as a “mere” reflection of the world. They play an essential part in the societal production of meaning, knowledge and power, thereby shaping the realities we live in. As an example of this, advertising constantly produces knowledge on both sexuality and the gendered idea of beauty, fixed as a presupposition onto women and female femininity.’

Furthermore, Innocenti chooses a common visual tactic used in contemporary advertisements, where adult women are portrayed as naïve and childish, while younger girls are shown as self-confident and mature. Marshall notes that the choice of putting sexualised women in a picture book makes it unsuitable for children. However, these are ‘the images that children and adults see every day on the street, on subways, in magazines and newspapers, and on television’ (2015: 167), a context where sexualisation is not thought to be controversial for younger audiences. The contrast between the format – the picture book, usually addressed to young readers – and the issues presented in the work were emphasised by many critics and reviewers. In addition, Sophia gets lost not just because of the chaos of the city, but also because her attention is caught by shop windows. She desires objects of consumption and loses her way: Innocenti also presents a clear critique of consumerism and materialism.

When the girl gets lost, she is suddenly surrounded by a gang of men that follow her in a narrow and deserted street. The girl is rescued by another man, ‘a smiling hunter’, a stranger ‘dark and strong and perfect in his timing’ (Frisch, 2012).

The man’s portrayal focuses on his physical, psychological and symbolic strength, opposed to the vulnerability and innocence that characterise the girl. In Marshall and Gilmore’s opinion (2015), the story turns from the possible gang rape to the participatory experience: Sophia is seduced by the ‘romantic brute’ and immediately trusts him.

The man gives the girl a ride to her grandmother’s house and the atmosphere turns grey, with a storm slowly approaching. The reader sees the man entering Sophie’s grandmother’s house, while Sophia seems completely unaware of her fate.

Then the story is interrupted by an ellipsis. Readers perceive, rather than see, the rape, and its omission strengthens this possibility. Trauma is addressed as something unknown, that cannot be represented or spoken. Frisch and Innocenti prefer to depict the moment through silence, in the gutters: it possibly represents the silence of women, both victims and witnesses of such a brutal act, women who do not dare to speak about it. Therefore, the reader, a silent witness, ‘must draw on a larger repertoire of graphic knowledge about girls’ bodies, public spaces, and sexual vulnerability, to imagine it’ (Marshall, 2015: 167).

Finally, the authors offer two different endings: in the first one – inspired by Perrault’s version – the girl is not found and is probably murdered; in the second – like in the Brothers Grimm’s fairy tale – Sophia is rescued. In both cases, rape is not represented but clearly hinted.

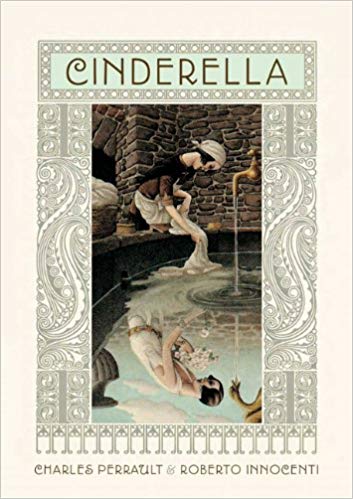

Similarly, Innocenti also focuses on the figure of the stepmother, who is explored in depth and plays a central role in the development of the plot. She is a mysterious character who is often portrayed while drinking alcohol and smoking cigarettes, characteristics that would not be likely in Perrault’s time. These elements help the reader to label the stepmother as the villain of the story: she is a character with a mean personality and despicable habits. On the other hand, an attentive reader might consider her a problematic woman and might wonder why she was given such an evil personality and bad vices.

What is particularly curious in Innocenti’s version of ‘Cinderella’ is the happy ending. In the last pages, we can admire Cinderella’s wedding. The two stepsisters are finally sorry for their behaviour and they are given partners as well. However, the last page of the book contrasts with the happy ending: Innocenti illustrates a concerned stepmother looking out of the window while holding a book, Cinderella by Roberto Innocenti. The book is opened on the page depicting Cinderella’s wedding, while the stepmother is, again, smoking cigarettes and drinking alcohol – there are many empty bottles on the floor. Although the stepmother is presented as the main villain of the story by Innocenti too, this final page creates contrasting emotions: the reader may think she deserved that fate, or may feel pity for the woman, now completely alone in the world. Consequently, readers are not provided with a totally happy ending since the story closes focusing on the stepmother’s misfortunes (Hennard Dutheil de la Rochère, 2016).

To conclude, inThe Girl in Red, the illustrator depicts modern cities and their contemporary dangers: media and their sexualisation and objectification of women’s body. In Cinderella, new spaces give the possibility to underline particular aspects of some of the characters, giving the reader new perspectives on the interpretation of the text. Therefore, the artist does not simply recontextualise the two stories, but clearly shows that fairy tales are possible in different eras and places, they prevail on time and are always contemporary. Innocenti demonstrates that archetypes can easily transcend space and time.

Works cited

Hennard Dutheil de la Rochère, Martine, Gillian Lathey and Monika Woźniak (eds), 2016, Cinderella across Cultures: New Directions and Interdisciplinary Perspectives. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press.

Frisch, Aaron (illus. Roberto Innocenti), 2012, The Girl in Red. Mankato, MN: Creative Editions.

Perrault, Charles (illus. Roberto Innocenti), 2013, Cinderella, Mankato, MN: Creative Paperbacks.

Marshall, Elizabeth, 2015, Fear and strangeness in picturebooks: Fractured fairy tales, graphic knowledge, and teachers’ concerns. In Janet Evans (ed.) Challenging and Controversial Picture books: Creative and Critical Responses to Visual Texts.

Abingdon and New York: Routledge, Part II, Paper 8.

Marshall, Elizabeth and Leigh Gilmor, 2015, Girlhood in the gutter. Feminist graphic knowledge and the visualisation of sexual precarity. Women’s Studies Quarterly 43.1,2, pp.95–114.

McNair, Brian, 2002, Striptease Culture: Sex, Media and the Democratization of Desire. London: Routledge.

Myers, Lindsay, 2008, Roberto Innocenti: HCA Illustrator Medallist 2008. Bookbird: A Journal of International Children’s Literature, 46.4, pp.31–37.

Rossi, Leena-Maija, 2007, Outdoor Pornification: Advertising heterosexuality in the streets. In S. Paasonen, K. Nikunen and L. Saarenmaa (eds) Pornification: Sex and Sexuality in Media Culture. Oxford: Berg, pp.127–138.