I Want to Be an . . . Air Stewardess: The Careers Comics of GIRL (1951–1964)

Louise Johnson

I was always going to read GIRL. Was there ever any other choice for somebody who grew up in the eighties reading the weekly Twinkle (1968–1999) and began to collect books in the nineties, driven by the republishing of the Chalet School books by Elinor M. Brent-Dyer?

It was a heady period for anybody, let alone one who had an intimate knowledge of their local Waterstones and capable of grimly hoarding their pocket money for weeks on end.

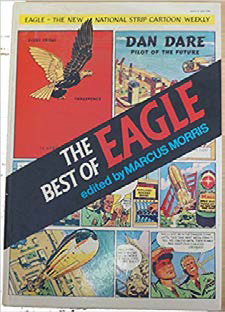

Twinkle and the Chalet School books set me on the way towards GIRL, but I needed a compilation of The Best of EAGLE – bought by an elder brother and left behind when he moved out – to give me that final push. It was here that I found comics that were unlike anything I’d ever seen before, devoid of that rather rounded sweetness that pervaded every page of Twinkle. Instead of having bouncy ponytails of impeccable quality, the characters of EAGLE went to Mars. The difference was remarkable. These were comics that spoke to me. They offered a mode of storytelling that the eighties and nineties – for all their strange brilliance – simply could not offer.

And so I found my way towards GIRL, a weekly comic published between 1951 to 1964 by Hulton Press. Hulton Press was the home of EAGLE, an established title on the shelves at that point, and GIRL came from the same creative team. The editor of EAGLE, Marcus Morris, had sought to create a periodical that was especially for girls and went so far as to directly ask readers for help in ‘getting to know for certain what sort of things you like’. At first, the circulation was poor and Morris decided that this was due to the ‘mistake of not taking sufficiently into account the difference between the masculine and the feminine psychological make-up. The difference is a very real one’ (Morris and Hallwood, 1998: 164). Things had to change: more girls were reading EAGLE than GIRL and so Morris adopted a new editorial stance:

[W]e had made Girl too masculine. We therefore made it more romantic in its approach, more feminine. I worked on the theory that you should be a good deal more personal in your motivation in a girls’ paper. (p.164)

A rebranding occurred and alongside the introduction of iconic – and suitably ‘feminine’! – strips such as Belle of the Ballet by George Beardmore and John Worsley and the redesign of the logo, GIRL saw its circulation figures increase from 500,000 (p.163) to a steady 650,000 (p.164). It was well on its way to becoming a ‘watershed’ publication within British comics, not just for its quality of storytelling but also for the rich production values (Gibson, 2015: 43).

What Children Think of Their Comics (Pumphrey, 1964) provides an interesting reading of this new periodical on the block. The author, George Pumphrey, carried out a small-scale quantitative survey of children and their reading habits in the 1950s and published both his findings from this survey and his thoughts on British comics in general. He writes with a certain acerbic appeal that a particular issue of GIRL has

‘2 quite good’ written stories alongside some useful occupations: ‘Patterns. Quiz’, several special features: ‘Film – Tommy Steele. Pop music material. Pin-up of Joe Brown. Good Discussion’

before giving it the overall rating of C+ (pp.38–39). It may seem a somewhat hard rating, but only three comics in his wide-ranging survey receive an A:

Animals possesses ‘excellent pictures and features on animals’ (pp.40–41), Knowledge has ‘material of great educational interest’, and Understanding Science has ‘great deal of interesting authentic information’ (pp.44–45).

In direct contrast to this, Elvis Monthly and Billy Fury Monthly receive a D, alongside Superman and Superboy, which both suggest ‘success through magical powers and physical strength’ (pp.43–45). Even from this brief reading, it’s clear to see that, for Pumphrey, comics must be educational, preferably non-fiction and scientifically orientated – and the fewer photographs of teen pop idols, the better. Elsewhere he devotes time towards examining the ‘What’s Your Worry’ letter column in GIRL and in commenting favourably on how it seeks to support readers through complex personal problems – yet the C+ rating remains. It’s perhaps redundant here to wonder if a teenage girl’s opinion would have differed from that of an adult man . . ..

GIRL was more than what many people made of it. It did not shy away from the real world, and concerned itself with exploring both the fictional and non-fictional experiences of girlhood and the transition into young womanhood. It is in this latter space that we find the ‘I want to Be’ strips, a repeating series of comics that explored the careers available to a young woman and how to achieve them.

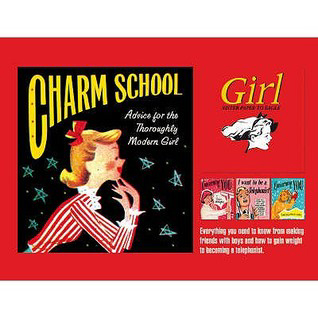

Notably, gathered and sold in a standalone volume, I Want to Be

. . . A Girl Book of Careers (1957), due to their fierce popularity, were republished nearly 50 years later in Charm School: Advice for the Thoroughly Modern Girl (2006). They are fascinating and somewhat compulsive reading, indicative not only of an early form of careers education but also of societal views about the figure of the girl herself. Each comic is introduced with a brief precis of the girl and her skill. Ruby ‘likes working with her hands’ and wants to be a plastics designer (p.75); Linda is ‘very observant’ with ‘a good memory’ and wishes to be a continuity girl (p.51). Alice is a ‘modern young woman’ and yearns to be a ‘steno-typist’ (p.63). For a modern reader, it’s easy to find humour here. Jane, who wishes to be a chiropodist does not directly touch a foot (p.69); Felicity, a personnel officer, spends more time playing table tennis and having lunch than she does doing paperwork (p.37), and Jill, a policewoman, receives a uniform that is made to her own measurements and ends her panel dancing in the arms of a fellow officer (p.47).

Yet, placing amusement aside, these are clearly comics of ‘ambition and achievement’ intended to ‘introduce girls to the new possibilities that the post-war reconstruction offered women’ (Philips, 2000: 78). The careers presented are diverse, albeit a diversity that locates itself squarely within the remit of careers available to middle-class girls of a predominantly white and European background, and embrace some unusual and creative options. Lois wants to demonstrate domestic appliances (Russell, Charm School, 2006: 71), Anita wants to be a radio technician

(p.74), and Peggy wishes to be an architect – having been inspired by designing her own dolls’ house as a child (p.53). However it’s noticeable that though all careers are available, some are – to paraphrase Orwell – more available than others. The I Want to Be . . . offers long-form descriptions of careers such as teaching (p.16), librarianship (p.12) and midwifery (p.24) but stays away from elaborating further on how to enter architecture, become a radio technician or how to demonstrate domestic appliances. It’s perhaps of interest at this point to mention that the most dominant adverts in the I Want to Be . . . come from established high-street financial institutions including: Barclays Bank: ‘agreeable work in congenial company, with a good salary and excellent prospects of promotion’ (p.61); Lloyds Bank: ‘Marriage need not interrupt a successful career’ (p.5); and Midland Bank: ‘You really feel you’re someone when you join the staff of the Midland Bank’ (p.55). The presence of these reinforces the inevitability that a vast amount of GIRL’s readership would work for one of these – or a similar – institution.

The reader of the I Want to Be . . . strips is asked to inhabit a strange position. She is to be both a contradiction and an expectation (Philips, 2000: 77), to know her place in the world and yet exert considerable effort to exceed and improve upon it. The ‘brilliant’ Sylvia must spend ten years training, alongside an initial expenditure of £200 – the equivalent of £4,700+ today, to qualify as a barrister and earn ‘about a thousand pounds a year’ (Russell, Charm School, 2006: 59). The emphasis on this initial payment of £200 is marked: ‘this is a commitment for people with only the financial ability to do so’. Jane, a chiropodist, needs financial support from her father to set up her private practice and ‘hopes to increase her clientele in time, so that she can earn her living by her own efforts’ (p.69). She’s clearly not earning enough to support herself at this point. Sue, a kennel-maid, also requires paternal assistance and ends up owning a small kennels in Sussex with her father where they breed and show cocker spaniels (p.25). A girl requires financial support, parental permission and a certain amount of privilege in order to have a career, it seems.

The artwork of the I Want to Be . . . strips is also revealing at this juncture; this is no space for the vibrant panelling of Dan Dare which stretch to fully express the magnitude of alien landscapes (Morris, 1977: 32) or to fall away entirely (pp.28, 29, 31), nor the dynamic speech of ‘Storm Nelson – Sea Adventurer’ which breaks panel boundaries with exuberant freedom (pp.113,119, 120). This is a comic that thrives on regularity, precision and fixed, impenetrable frames. Each comic is of a standard six panels – only on rare occasions does this extend to a full-page strip – and speech remains located within a specific panel. The white space between remains inviolate, whilst the first panel itself sees a headshot of the girl herself. Normally looking out from the page and smiling at the reader, she is accompanied by a brief introduction to her and her skills. The overall effect is peculiarly reminiscent of the ‘Girls In Pearls’ pages from Country Life – these are girls to be seen and viewed, rather than girls in possession of anything approaching personal and independent agency.

What then to make of these comics which promise liberation on one hand but assert subtle layers of control and expectation throughout? I’m conscious that I’ve provided only a brief introduction to them here, and an even briefer contradiction to their complexities, and that I’ve done this with the liberation of a contemporary perspective. Yet despite those caveats, I hope this shows a vital point of the discourse of ‘being a girl’ in the 1950s. Stephanie Spencer recognises that comics such as GIRL provided an introduction into that community of girlhood whilst simultaneously shaping the nature of what that community might be (2005), and, indeed, that despite the onset of ‘full employment’, the option of young women remained somewhat limited. My own family supports this reading; my mother remembers being furious at the likelihood of earning less than her male counterparts and deliberately chose to enter a career with some parity. The movement towards equal pay – as most recently demonstrated in a series of high-scale pay review cases at the BBC – is still yet to be resolved. Perhaps it’s in this nexus that my reading of I Want to Be . . . can find most critical purchase: this is a comic that showed young female readers the potential of what was open to them. It also showed them what stood in the way.

Works cited

Primary work

Morris, Marcus (ed.) (1957) I Want to Be . . . A Girl Book of Careers. London: Hulton Press.

Morris, Marcus (ed.) (1958) Girl Annual: Number 6. London: Hulton Press.

Morris, Marcus (ed.) (1954) Girl Annual: Number 3. London: Hulton Press.

Morris, Marcus (ed.) (1952) Girl Annual: Number 1. London: Hulton Press.

Russell, Lorna (ed.) (2006) Charm School: Advice for the Thoroughly Modern Girl. London: Prion.

Secondary works

Gibson, Mel (2015) Remembered Reading: Memory, Comics and Post-War Constructions of British Girlhood. Leuven University Press.

Jones, Dudley and Tony Watkins (eds). (2000) A Necessary Fantasy? The Heroic Figure in Children’s Popular Culture. New York: Garland.

Morris, Marcus (ed.) (1977) The Best of EAGLE. London: Michael Joseph.

Morris, Sally and Jan Hallwood (1998) Living With Eagles: Marcus Morris, Priest and Publisher. Bath: Bookcraft.

Philips, Deborah (2000) Girls’ Own Stories: Good Citizenship and Girls in British Postwar Popular Culture. In Dudley Jones and

Tony Watkins (eds) (2000) A Necessary Fantasy? The Heroic Figure in Children’s Popular Culture. New York: Garland. pp.73–85.

Pumphrey, George H. (1964) What Children Think of Their Comics: With an Analysis of Current Comics and a Brief Assessment of Present Trends. London: The Epworth Press.

Russell, Lorna (ed.) (2007) The Best of Girl: Sister Paper to EAGLE. London: Prion.

Spencer, Stephanie (2005) Gender, Work and Education in Britain in the 1950s. Aldershot: Palgrave.

Louise Johnson is a first year PhD candidate with the Department of Education, University of York. She researches girls in children’s literature, with a particular interest in school stories and fictional communities of girlhood. She can be found online at her book blog didyoueverstoptothink.com, and also co-hosting the literary fiction podcast Novel Gazing: https://bookriot.com/listen/shows/novel-gazing/.