Arai Ryoji: Seeing the World from Innocent Eyes

This HCAA nominee spotlight is courtesy of Fuling Deng and Yaxi Wang, in partnership with Evelyn Arizpe and the Erasmus Mundus programme, the International Master’s in Children’s Literature, Media and Culture (IMCLMC).

Vibrant, childlike and mischievous! Let’s step into the nonsense and playful imaginary world created by Japanese picturebook master Arai Ryoji through eyes of innocence.

I suddenly want to sing a song. Shall I?

This was what the first Asian winner of the Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award, Arai Ryoji, said when he was about to give an acceptance speech. The judges of the most prestigious award in children’s literature gave Ryoji the following comment (2005):

…an illustrator with a style all of his own: bold, mischievous and unpredictable. His picturebooks glow with warmth, playful good humour and an audacious spontaneity that appeals to children and adults alike.

Born in 1956 in Yamagata, Japan, Ryoji spent most of his childhood painting, with his drawings popping up everywhere – from leaflets to arithmetic books, even on the wall. Ryoji’s first contact with picturebooks was Goodnight Moon (1947); young Ryoji was confused about how a rabbit could live in a house with a tiger-skin carpet and keep a cat and a dog as pets. It does not make sense, but readers naturally accept the nonsense of picturebooks. Ryoji was absolutely attracted to the freedom and openness of this visual storytelling art.

After graduating from art education at Nippon University, Ryoji worked as a full-time illustrator in the company. However, he suffered from cognitive dissonance due to a long-term suppression of creative expression, which rekindled his dream to make picturebooks. At 34, Ryoji started his picturebook career by publishing Slowly and Gradually (1991).

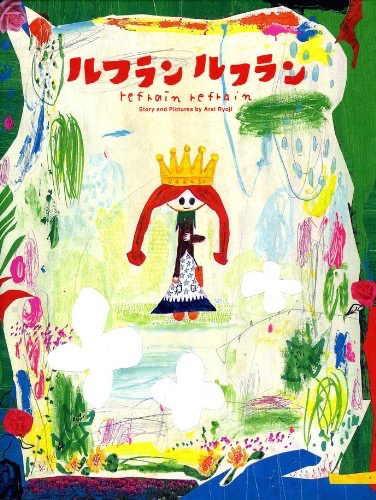

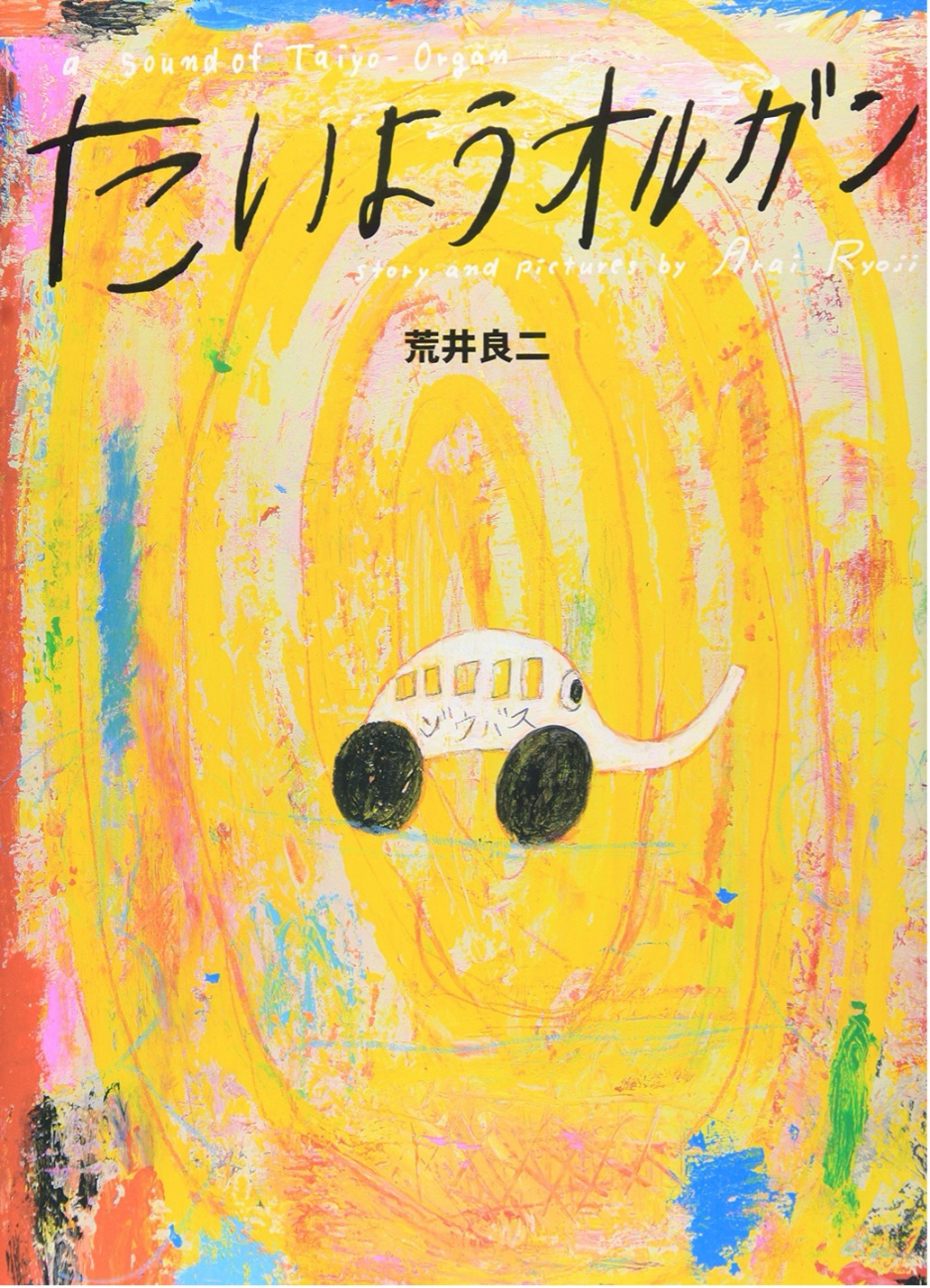

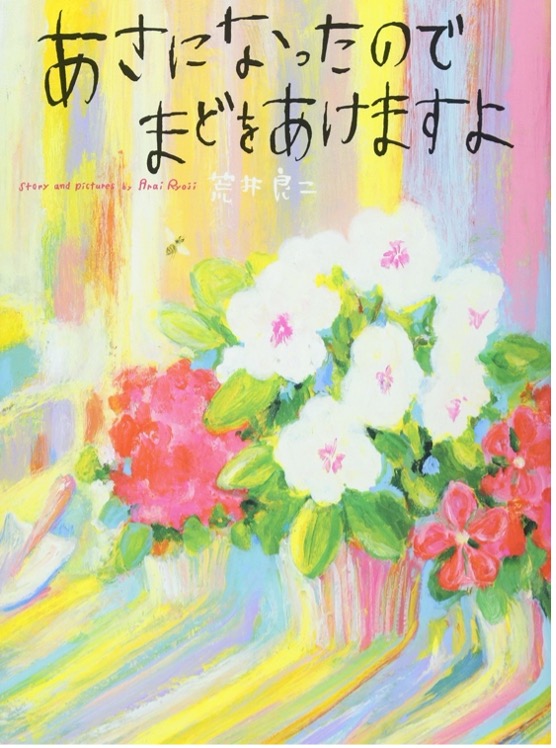

Ryoji has now become one of the best-loved and most highly acclaimed illustrators in the world. His picturebooks have been honoured with awards in Japan and abroad, including the Special Award at the 1999 Bologna Book Fair for A Journey of Riddles (1998); the publisher Kaisei-sha’s 1999 picturebook award for A Forest Picture Book (1999); the 2005 Japan Picturebook Prize for Refrain Refrain (2005); the 2017 JBBY Prize and 2008 IBBY Honour List for The Sun Organ (2008); the 2012 Sankei Juvenile Literature Publishing Culture Award for It’s Morning, Let’s Open the Window (2011); and the 2021 Japan Picturebook Prize for Children are Addicted (2020).

The artist’s creative process seems to be limited by neither mediums nor painting methods. He squeezes pigments directly onto paper where he paints by hand, or assembles sketches into a collage with ballpoint drawings framing the work. Even thumb-size pencils are employed as inconvenient tools to avoid “mature” and “adult-like” depictions, and instead seek out the magic of freedom and unpredictability. Ryoji once said:

I don’t think delicately fabricated plots or technically skilled illustrations could touch children. […] I try to throw away the adult part in my heart and pull out my inner child.

Considering grown-up experiences as a white elephant, Ryoji works hard to convey through illustration a passion and freedom that children can identify with. He followed this philosophy while creating The Sun Organ (2008), where the protagonist sun, having short arms and thin fingers, plays a tiny organ that is totally out of proportion to his big-faced round head. Other details, like a bird’s nest on the top of a mountain and sheep in red with green triangular heads, also challenge adults’ expectations of perspective and common sense by subverting order and convention to form connections between unrelated things – something that children are particularly adept at.

The flexible composition combines dynamic pencil strokes with a bold colour palette, thereby creating a doodle effect that allows children to feel intimately connected to the work and its artist. This may even give them a sense of achievement sparked by the realisation: ‘it turns out that the master’s paintings are similar to mine’. More than a storytelling medium, Ryoji’s works could be a motivation for children to create their own stories.

In a forest called ‘think’, a group of animals are discussing how to transform the clearing, for example by making a hot spring or turning it into a lake. Everyone’s ideas are celebrated except for Raccoon’s, who suggests keeping the place as it is. The discussion starts over and becomes extremely chaotic. Unexpectedly, a cow comes to graze on the grass, driving away the animals. The clearing grows silent and after a long time, the cow leaves. The clearing is still empty, with the sound of the animals’ discussion deep in the forest.

I Intend to Do (1997) is a good example of Ryoji’s books that highlights his nonsense philosophy. The picturebook allows children to have fun with their imagination without the pressure of looking for answers. While adults may question the book’s bizarre logic, it leads to dramatic possibilities that children favour a lot. Ryoji’s works are a tribute to children’s minds and demonstrate the power of vagueness: they are picturebooks without a direct aim and clear direction, through which various ways of interpretation become possible.

Aside from nonsensical humour, some of Ryoji’s picturebooks synthesise essential rhyming text and bright-coloured images in a well-balanced pace, creating a joyful symphony that brings poetry, imagination, and deep thoughts into everyday existence. It’s Morning, Let’s Open the Window (2011) does not have a narrative, but simply depicts everyday scenery outside the window, such as high-rise buildings, tranquil countryside, and calm sea, linked by the melodic words, “It’s morning, let’s open the window!” Ryoji captures the alienness of familiar window views and enchants readers through exquisitely coloured illustrations – so much so, that readers might even hear the joyful voice that welcomes the morning lingering in their ears.

Ryoji’s works are a reminder of everyday happiness that is always overlooked, and this is also shown in Today’s Moon is Round (2016) that gives all of Earth’s inhabitants gentle comfort by the end of the day. The little baby in the doll cart, the stray cats in the park, and even the whale leaping up from the sea are all enjoying a simple night full of moonlight. This book displays Ryoji’s ability to transform the atmosphere of the story into colours and lines that can be felt, seen and heard, creating a lively yet peaceful atmosphere. Through Ryoji’s mastery of colours, readers are immersed in the hopeful and poetic atmosphere of the pictorial world flowing with melody and imagination.

Arai Ryoji is an artist with a free soul and a childlike heart. His innocent eyes and liberated expression explain why he won the Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award which is intended to celebrate authors standing by children. Japan’s NHK TV called him “Arai Ryoji of the world” due to his loyalty to his inner child, which brings unfettered vigorous vitality to his works that cross the borders of language and age to stir the hearts of readers.

References

The Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award. (2005) Ryoji Arai. Available at: https://alma.se/en/laureates/ryoji-arai/ (Accessed: 28/08/2021).

Thinkingdom Children’s Books (2020) He Haizi Zhanzai Yiqi de Ren [The Artist who Stays with Children]. Available at: https://www.sohu.com/a/424428913_120083280 (Accessed: 28/08/2021).