Fashioning Dolls: Different Treatments and Attitudes Revealed in Children’s Texts

Figure 1

John Wollaston Mann Page and His Sister Elizabeth. Original portrait in the collection of the Virginia Historical Society, Richmond, Virginia. (Virginia Historical Society, Accession no. 1973.16). This is a faithful photographic reproduction of a two-dimensional, public domain work of art, courtesy of the Virginia Historical Society.

Susan Bailes

Making use of a range of primary sources, I propose to explore the treatment of needlecraft and fashion in a selection of children’s doll texts.

Many eighteenth-century paintings remind us of how the dolls that appear in portraits were expensive items, an indicator of class, the majority associated with females. John Wollaston’s portrait of Mann Page and his sister Elizabeth (ca. 1757) is one such example. The artist shows them both smartly attired, happily gazing out at the viewer. A living red parrot is perched on the boy’s left hand, whilst his right hand carefully holds onto a leash. His sister holds an inanimate object, a doll, beautifully clothed in finery, a golden, silk, full-length dress closely resembling her own attire with the same square neckline. (See Figure 1.)

Dolls in this period carried associations with the fashion trade and were chiefly targeted at the female gender. Antonia Fraser in her History of Toys (1966) explains how the fashion doll was an eighteenth-century phenomenon even though as far back as the fifteenth century European royal houses and nobilities ordered fashion dolls on a regular basis. Dolls called ‘Pandoras’ were sent out by French fashion houses to the continent for their details of dress and coiffure as fashion magazines and plates were not available as a source of information at that time. Dressmakers illustrated their skills in miniature for their clients. In addition, human-sized versions of the fashion doll came into existence.

Aristocratic and bourgeois women started collecting the dolls. Moreover, the dresses were often taken off the doll upon its arrival and worn by the recipient. The dolls were even granted diplomatic immunity during the Wars of the Spanish Succession (1702–1714). Native English fashion dolls travelled to America as newspapers at the time report.

Figure 2

William Hoare Christopher Anstey and his Daughter Mary © National Portrait Gallery, London.

There was little to distinguish the dolls used to display the latest fashion from those used as toys. Women viewed them with the girls who played with them and girls could see, with the dolls dressed in adult styles, pictures of womanhood, and imagine themselves grown up. In the painting by William Hoare of Christopher Anstey and his Daughter Mary ca. 1776–1778, we see the potential waywardness of girls. Anstey the poet gazes aloft in concentration, whilst his daughter, smiling, tugs at his coat, urging him to look at her doll. This diminutive object epitomises extreme eighteenth-century fashion. We notice the very tiny waist, the exaggerated towering high hairstyle added to with jewels and feathers. (See Figure 2.)

Apart from conveying the latest fashion trends, it is important to note that dolls played a significant part in female education. A good wife needed to master sewing and dressmaking. Like samplers, dolls functioned as study tools, and exemplars of accomplishment. If a girl had an undressed doll she could make outfits for it, thus learning sewing and garment construction.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau in Emile’s (1762) last chapter entitled ‘Sophy, or Woman’ deals with her education as she is to be Emile’s wife. Rousseau writes of girls’ education in the world of dolls and clothing. Love of finery was the defining characteristic of ‘even the tiniest little girls’ and revealed true feminine nature as ‘the art of pleasing’ through appearance. A girl playing with her doll epitomises women. There are warnings. Female attention to clothing should not be excessive. A girl’s interest in dolls should be encouraged as it presaged a woman’s natural concerns about pleasing men and learning subservience.

Observe a little girl spending the day around her doll, she is constantly changing its clothes, dressing and undressing it hundreds and hundreds of times, continuously seeking new combinations of ornaments well- or ill-matched …. She is hungrier for adornment than for food …. She is entirely in her doll …. She will not always leave it there. She awaits the moment when she will be her own doll. (p.367)

The English are credited with the next significant development as they invented paper dolls which were much more readily accessible and which replaced the fashion dolls. Paper dolls have remained popular ever since and are playthings today.

Figure 3

Joseph Highmore Susanna Highmore c. 1740–1745 oil on canvas 91.5 × 71.1 cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Felton Bequest, 1947 (1741–4).

Joseph Highmore’s portrait of his daughter Susannah (ca. 1740–1745) beautifully captures this significant shift to paper dolls. We see her holding up a miniature depicting a woman in Turkish dress which appears to be taken from the portfolio or scrapbook of paper dolls lying on the table. (See Figure 3.)

Children’s literature associated with playing with paper dolls soon followed. Between 1810 and 1816 the London toy firm S. & J. Fuller ingeniously produced a series of little books which they sold at their shop, Temple of Fancy at Rathbone Place. Each set was packaged in a small sheath and made up of a black-and-white moral history of a young person, often in poor verse, divided into scenes. Accompanying the text were a number of hand-coloured cut-out images printed separately on card, showing costumes plus a single hand-coloured cardboard head which slotted into the different costumes with hats added.

These books were tasteful and attractive but expensive to produce. The cheapest of them retailed at five shillings and the most elaborate one, Young Albert or the Roscius (1811) based on young Betty, the boy actor, cost eight shillings, so they would have been marketed towards the upper class.

Figure 4

Paper doll bodies in costumes, to be paired with doll heads. From The History of Little Fanny.

One extremely popular example is The History of Little Fanny (1810). (See Figure 4.)

See Fanny here, in frock as white as snow,

A sash of pink, with long and flowing bow,

Shoes that sit tight and closely to her feet,

Her whole appearance tidy, clean, and neat;

And in her arms a favourite doll she bears,

The only object of her hopes and cares;

Fanny with books will ne’er her mind employ

For play’s her passion, idleness her joy. (pp.2–3)

Fanny’s fall from grace involves clothing. Her mother refuses to let her wear recently bought finery in inclement weather but Fanny persists and goes out, with serious consequences. Her costume changes to that of a beggar. Seeing Fanny in all her finery, a beggar has snatched the girl and forced her to roam the streets, tattered and torn. Various episodes follow, until, fortunately, she is sent on an errand, wearing a modest coloured frock, to her own home and is forgiven by her mother and happily restored, having learnt her lesson. Instead of holding a frivolous doll, the final illustration accompanying the text, shows reformed Fanny holding a book.

She’s now no longer idle, proud, or vain,

Eager her own opinion to maintain;

But pious, modest, diligent, and mild,

Belov’d by all, a good and happy child. (p.15)

The moral is in keeping with thoughts expressed by the Edgeworths in Practical Education (1798) who praise the doll as follows.

A means of inspiring girls with a taste for neatness in dress, and with a desire to make those things for themselves, for which women are usually dependent upon milliners, we must acknowledge their utility; but a watchful eye should be kept upon the child, to mark the first symptoms of a love of finery and fashion. (p.10)

Ironically, although the text may present values of obedience, respect for elders, modesty, cleanliness, intellectual pursuit, whilst deploring a love of finery and fashion, the moral can be ignored. Indeed, the structure with the separate costume items allows the child reader to decide what is important with the result that surviving copies often have pristine texts accompanied by grubby, worn, and even missing, costume items.

Figure 5

Another early doll narrative using dolls as vehicles for improvement is Maria Elizabeth Budden’s Right and Wrong Exhibited in the History of Rosa and Agnes (1815) (see Figure 5), which combines instruction with delight. In Chapter VI two sisters, Rosa and Agnes, are each given a large, unclothed female doll so the girls will gain from the employment of making their dolls clothes using the materials provided in accompanying boxes.

Rosa asks for her mother’s advice for her doll’s clothing but chooses to ignore it completely as she believes the process is too time-consuming. Her mother remarks ‘Done very quickly, Rosa, but I fear not done very wisely’ (p.103). Meanwhile, Agnes follows the advice and takes great pleasure in her achievements. When Rosa uses a pin to fix the flimsy shift, she pricks her finger and blood appears on her sarsnet (a fine, soft fabric, often of silk, made in plain or twill weave and used especially for linings). Younger children beg to see the dolls but there is danger that they may damage or derange their dress. Agnes is not concerned as she had made her clothing carefully but Rosa ‘knew it was so carelessly dressed, that one tug would draw off all the clothing, and the silk, once dirtied could not easily be cleaned again’ (p.109). Adding further moral points we learn that Agnes chose plain materials for her garments which are easily laundered.

This moral tale continues with the author denouncing Rosa as she would not be the dutiful child, kind sister or faithful friend. She therefore lived despised and died unlamented. Her impatience is held up for reprobation, whereas Agnes’ perseverance is rewarded. As the concluding chapter emphasises ‘Each duty was performed in its right place, and at its appointed time …. Thus one virtue leads to more. We need no prompting in reply to the question “Reader! which will you be? Rosa, giving way to wrong. Agnes, persevering in right?”’ (p.171)

In Julia Charlotte Maitland’s The Doll and her Friends or Memoirs of Lady Seraphina (1852) the doll narrator states that she ‘belongs to a race the sole end of whose existence is to give pleasure to others’, adding ‘some may attribute to our influence many a habit of housewifery, neatness, and industry’ (p.8). She is bought for a little girl, Rose, who states ‘I only want a sixpenny doll not dressed’ (p.30). In the final chapter the family must leave for Madeira so Rose gives the doll to her niece Susan, who has no money to spend on toys, and very little time to play with them, Rose’s dressmaking skills are not up to Susan’s high standards, who scorned all makeshifts. Everything was scrupulously finished. The newly created doll’s wardrobe is proudly displayed by Susan’s mother and generally admired. One day Sarah, the family’s housemaid arrives and explains the family requires white calico shirts for Rose’s brother Willy. Susan’s mother is not well enough to undertake this enormous task, but

Sarah took me up, and turned me from side to side. Then she looked at my hems then at my seams then at my gathers, while I felt truly proud and happy, conscious that not a long stitch could be found in either. (p.79)

Figure 6

Figure 7

Examples of Queen Victoria’s Dolls. From Queen Victoria’s Dolls. Lady Arnold (left) and Lady Bulkley (right).

Figure 8

The satisfying outcome for Susan’s careful needlework is the reward that she is good enough to help her mother and be paid much needed money. (See Figure 6.)

Making dolls’ clothing became universal and was highly regarded as appropriate for young girls, even Princess Victoria, the future Queen, undertook this task. My edition of Queen Victoria’s Dolls (1894) was published with her approval and shows her amazing collection of small, five- or six-inch wooden dolls usually dressed from some costumes she saw either in the theatre or private life. One hundred and thirty-two dolls are preserved and the Queen dressed no fewer than 32 herself. (See Figure 7.)

Frances H. Low writes in the introduction:

The workmanship in the frocks is exquisite; tiny ruffles are sewn with fairy stitches; wee pockets in aprons are finished off with minute bows – little handkerchiefs not more than half an inch square are embroidered with red silk initials. (p.70)

Unsurprisingly a burgeoning number of publications in the nineteenth century were issued such as Dolly’s Dressmaker published in London in the early 1860s, which contained patterns and hand-coloured pictures for doll’s clothes. Competitions to dress dolls to be given away to the poor were popular.

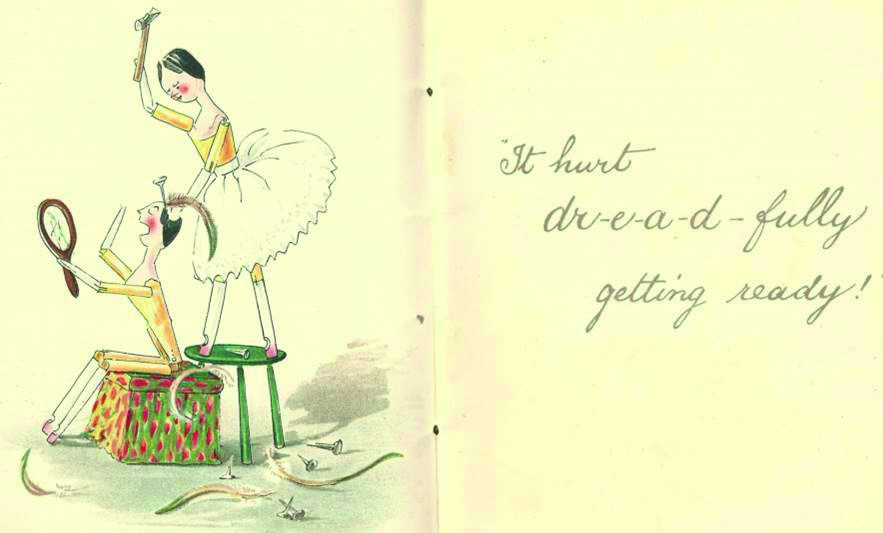

It is important to see how fashion and clothing dolls have been dealt with differently in children’s doll texts over time and developed in interesting ways. Illustrations in doll texts used details of the period and are highly entertaining. One example is the work of the Edwardian illustrator and author Kathleen Ainslie (1858–1936). Sadly, like many female illustrators her work is not well-known. Her books about the doll heroines, Catharine Susan and Me, give details of the period, including the latest inventions and even the Suffragette movement in a most entertaining, charming manner. Figure 8 cleverly shows the extremes the dolls, implied young females, go to for style and appearance as they prepare to be debutantes.

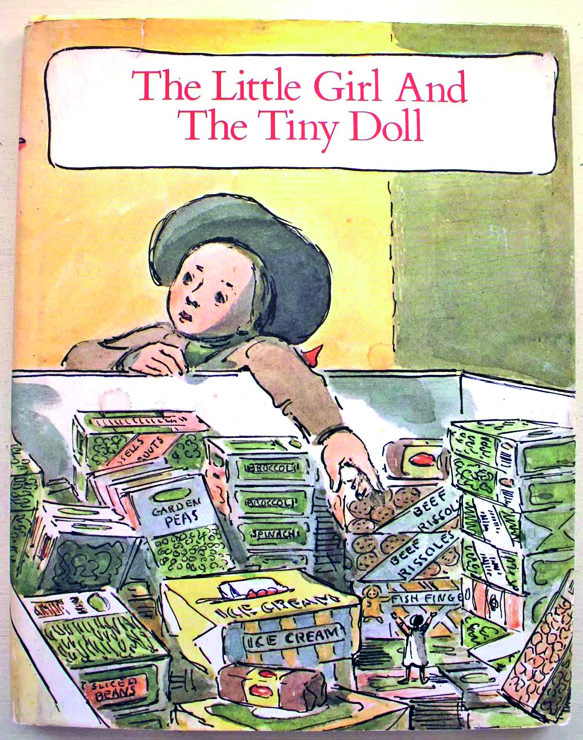

A more recent short doll text (1966) The Little Girl and the Tiny Doll, illustrated by Edward Ardizzone with text by his daughter-in-law Aingelda, involves a girl making clothes for a doll, but this time the emphasis is on how this handiwork demonstrates love and care, mirroring the relationship of parent and child.

‘There was once a tiny doll who belonged to a girl who did not care for dolls so her life was very dull’ (p.9) the story begins. And we learn that one day when the little girl was shopping in the supermarket with her mother, she threw the tiny doll into a deep freeze. So the tiny doll had to stay there, cold and lonely, and frightened by people shuffling all the food round her.

Another girl sees the doll looking so cold and lonely but dare not pick her up because she had been told not to touch things in the shop. However, she felt she must do something to help the doll and quickly set to work to make her some warm clothes, beginning with a warm bonnet made out of a piece of red flannel and daily delivering more items to the delighted doll. The warm clothing has a practical purpose for the doll in a freezer and immediately enhances the doll’s quality of life. Happily her mother asks the shopkeeper if her daughter can have the doll and the doll is taken to her home where she is much loved and played with a great deal. The care shown for the doll’s clothing is evidence of the care bestowed on the doll, just as a parent cares for a child. The focus is no longer fashion or vanity but love and consideration.

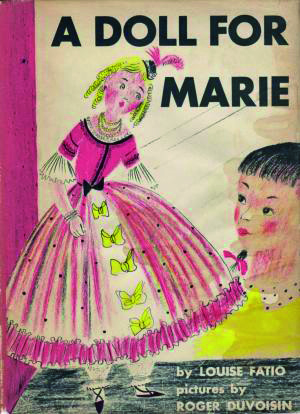

The same consideration is shown in A Doll for Marie (1957) by Louise Fatio with pictures by Roger Duvoisin. The Parisian antique doll is lonely until, one day, Marie the postman’s daughter sees her but is too poor to buy her. A lady does buy her but not for children, instead she adds her to her collection, somewhat like the antique shop, and places her on top of the piano. A cat smells her feather and knocks her onto a sleeping dachshund which seizes her roughly and carries out onto the pavement where she is fought over by a terrier and then abandoned in the gutter. ‘The antique doll lay on the pavement in her underwear, a most horrible situation for a princess of a doll.’ Marie spotted her and took her home, ‘holding her tight against her heart’.

The focus has clearly shifted from girls learning needlecraft skills to become accomplished women to that of love and the relationship between doll and child owner, which parallels that of mother/father and child. As time has passed the doll’s relationship with clothing has also altered, just as the role of the female in society has changed. More and more dolls, like Rumer Godden’s doll heroine, Impunity Jane, in the book of the same name first published in 1955, are played with by boys, in this case Gideon and a gang, as well as girls.

She is described here.

She was four inches high and made of thick china; her arms and legs were joined to her with loops of strong wire, she had painted blue eyes, a red mouth, rosy cheeks, and painted shoes and socks …. Her wig of yellow hair was stuck on with strong firm glue. She had no clothes …. (p.7)

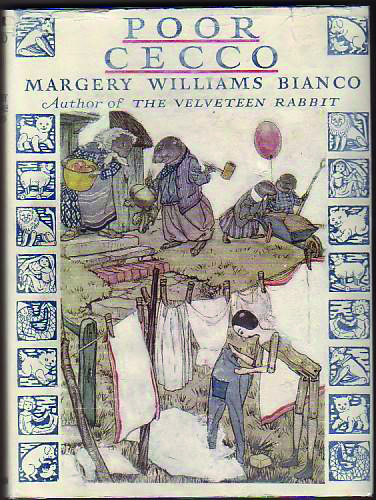

Dolls like Impunity Jane and Jensina in Poor Cecco (1925) by Margery Williams Bianco seek a life of adventure and excitement, freed from the constraints of the doll’s house and the stays and corsets of fine dresses.

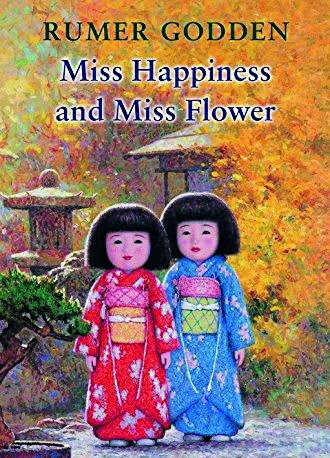

Children’s crafts and skills are encouraged in a completely different way. Godden’s Miss Happiness and Miss Flower (1961) concerns two dainty little Japanese dolls who live in England with Belinda and Nona. Nona is missing her home in India and spends her time doing things to keep the dolls happy. Consequently she sets about making a Japanese house and the reader learns about Japanese culture and traditions. Indeed the accompanying text allows the reader to play and carry out the instructions for him/herself.

In ‘Toys’ in Mythologies (1972) Roland Barthes appears to endorse Rousseau’s earlier argument as he argues that toys are essentially ‘a microcosm of the adult world’ and a girl’s doll is ‘meant to condition her to her future role as mother’. I believe the doll texts I have discussed here achieve far more.

Works cited

Ainslie, Kathleen (ca. 1906) Catharine Susan’s and Me’s Coming Out. London: Castell Brothers.

Anon. (1810) The History of Little Fanny. London: S. & J. Fuller.

Anon. (early 1860s) Dolly’s Dressmaker. London: A.N. Myers & Co.

Ardizzone, Aingelda (illus. Edward Ardizzone) (1966) Little Girl and the Tiny Doll. London: Longman Young Books.

Barthes, Roland (trans. Annette Lavers) (1972 [1957]) Toys. In Mythologies. New York: The Noonday Press.

Betty, William Hen West (1811) Young Albert or the Roscius. London: S. & J. Fuller.

Bianco, Margery Williams (1925) Poor Cecco. New York: George H. Doran.

Budden, Maria Elizabeth (1815) Right and Wrong Exhibited in the History of Rosa and Agnes. London: J. Harris.

Edgeworth, Maria and Richard Lovell Edgeworth (1798) Practical Education. Publisher unknown for first edition. Later editions by Cambridge University Press.

Fatio, Louise (illus. Roger Duvoisin) (1957) A Doll for Marie. Whittlesey House/McGraw-Hill.

Fraser, Antonia (1966) History of Toys. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

Godden, Rumer (1955) Impunity Jane. London: Macmillan.

Godden, Rumer (illus. Jean Primrose) (1961) Miss Happiness and Miss Flower. London: Macmillan.

Low, Frances H. (illus. Alan Wright) (1894) Queen Victoria’s Dolls. London: George Newnes.

Maitland, Julia Charlotte (illus. Hablot Knight Browne and W.T. Green) (1852) The Doll and Her Friends or Memoirs of Lady Seraphina. London: Grant and Griffith.

Rousseau, Jean-Jaques (trans. Allan Bloom) (1991 [1762]) Emile or On Education. London: Penguin Books 1991

Susan Bailes has taught in secondary and preparatory schools for 36 years and retired from a headship in Surrey after 13 years, in August 2012. She has always enjoyed English literature and drama, adapting and writing productions for pupils, and obtained her first degree from London University and her PGCE at Goldsmiths’ College. Whilst a deputy head, she was one of the early postgraduate students to obtain an MA in Children’s Literature at Roehampton University and continues to carry out research. She very much values serving on the committees of IBBY UK, the Children’s Books History Society and, more recently, IBIS, the Imaginative Book Illustration Society and regularly reviews books for these organisations. She has a particular interest in doll literature and all it reveals about the historical context in which it appears, along with illustrators. She now has a large, relevant collection. Her most recent talk ‘Kathleen Ainslie (1858–1936): A Forgotten Female Edwardian Illustrator of Children’s Books’ was published in Studies in Illustration, no. 66, Summer 2017