Distance, Direction and Landscape: A Cartographic Study in Picture Books

Dr Karenanne Knight

‘Twenty four feet is puddlenuts in Giant Country.’

From The BFG by Roald Dahl.

The concept of ‘far away’ to an under five-year-old is an intriguing one. But how do children learn about world landscapes at a younger age if we don’t introduce them to ‘far away’? Is the concept too inaccessible for the pre-school age group or is it just possible that they might understand more than we give them credit for when challenging such young minds with the most improbable of narratives?

I wanted to explore landscape through images with pre-school and reception-age children to understand their cartographic ability at a young age. I chose to look at direction and distance in particular as the main themes of the research.

The use of direction and distance in the landscape is central to map reading and I had a strong idea of the themes of the story that I wanted to develop and that I felt would work well in gaining an understanding of how children understood maps, landscape, distance and direction in particular. I therefore worked on a narrative that became the basis for the story, wanting it to reflect movement from A to B through a given landscape. I decided to use animals or insects that would be familiar to young audiences so that children were not confused by the main character and in order that they could concentrate on understanding the main themes of the story. So a main character, a butterfly, was to become a metaphor for a displaced child needing to overcome adversity and obstacles. As in all good stories, and it was with this in mind, I retold the story based on the themes of deforestation and displacement within the landscape. That landscape/setting would be a beautiful wooded forest, some might say the rainforest.

For the very young child I wanted there to be a forest, a river, something fairly familiar; but for the older child and the adult reader, the clues that ran through the book would give a greater sense of setting/landscape, continually finding new clues that made sense to this older audience as well as the very young.

The metamorphosis of the butterfly and her lost home seemed to identify with the idea of a child being displaced through deforestation and then migrating to different lands and landscapes. I also wanted to create the landscapes in the style of Eric Carle, someone I have admired for years and whose work (The Very Hungry Caterpillar) appeals to very young audiences.

The Wordless Picture Book

I wanted to create a fictional landscape and narrative with the intent to allow the child reader a chance to linger in the landscape and play within that space. The possibilities of constructing a wordless picture book, that somehow lent itself to the idea of landscape, was flourishing.

The project has three aims:

- to create a ‘work(s)’ for young audiences where narrative, landscape and cartography are central;

- to connect character, space and setting/landscape through the symbiotic relationship between narrative and cartography where the narrative, imagery and space of the creation are integrated with each other to the extent that they are intertwined and of equal importance;

- and finally to create images where ‘spatialness and landscape’ must be of cartographic value and therefore able to be read as such.

Within these aims my objectives were:

- To develop a wordless picture storybook developing basic cartographic understanding but particularly direction, distance and landscape.

- To develop believable imaginative spaces, in the reading of the artefacts produced.

- To develop a sense of story that will engage the child reader, whilst finding empathy with the heroine.

The wordless picture book was created and became a valuable asset to the research project. The layout of the book can be seen below and fulfils the initial landscape, distance and direction aims of the project.

The wordless picture storybook – Where Is Home?

(Illustrations to be read from left to right.)

Maps, cognition and pedagogy

It was important to convey the joy of story and therefore place, location/landscape and theme, to enable interaction with that ‘someplace, sometime and somewhere’ based on how the narrative sits within the book and in the real and imaginary world, and landscape.

In depicting landscape I showed how ‘place’ provides clues that a cartographer would automatically show in a map. The narrative I created exploits the potential of distance, landscape and direction, whilst associating the actual mapping process within that narrative.

Maps, books and cartographic skills

The book opens up possibilities of adventure to landscapes children only dream of, places never seen or heard about, filled with wonder whilst on the other hand empathising with the situation of the butterfly, a metaphor for a child who loses everything and has to move to a new part of the world. However, as we see, that part of the world, that landscape is not always the right one and so the cycle continues until they find ‘home’.

The picture book helps young children understand their way in the world through landscape, direction and distance, through time and place and appreciate the way we describe the route from A to B and the numerous deviations that might challenge us in between.

I enable children to picture and understand landscape through the pathways they select as they move through the story, following the journey the butterfly takes, literally helping them figure out where the landscapes/places, objects, countries and cities are in relation to one another and how that relates to the child’s place in the world. We can clearly see how the butterfly makes a journey through a variety of landscapes and can then retrace her steps enabling the child to engage and learn about wider spaces, landscapes, distance and direction.

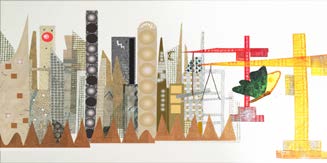

To do this, I produced three large, soft mats for the children to sit on and discuss when I visited the school and nursery. These were larger versions of the double-page spreads.

The first was the forest river mat (from a bird’s eye view).

The second was the dirty river mat (from a bird’s eye view).

The final artefact was the escape from Octopus mat. This mat was particularly developed in order to discuss landscape, distance, seas and oceans.

The results of the experiments using the cartographic devices of direction, distance and scale within the landscape

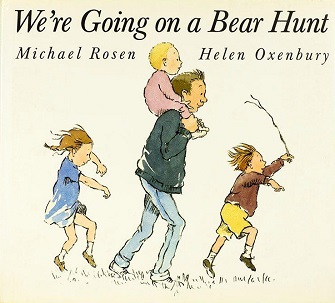

I worked with a class of 24 five-year-olds introducing We’re Going on a Bear Hunt which develops the idea of landscape and setting so well.

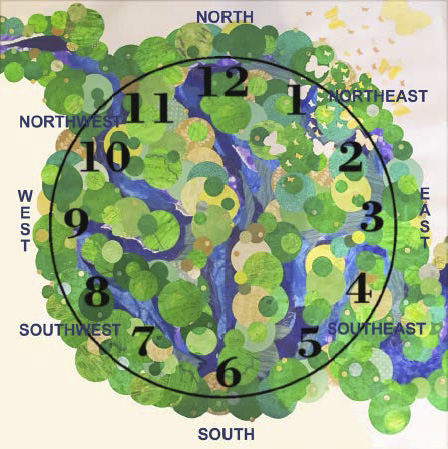

Initially I discussed distance and landscape using the above book. The children drew maps using the landscapes that generally followed a straight or circular line. Right and left were still difficult concepts to grasp for this age group, therefore north, south, east and west were obviously a difficult notion with which to create the journey/landscapes on the map. Improvisation through a clock and numbers did however, overcome some of these difficulties. Some of the children were more than able to say that the forest was at ‘three’ from the starting point, the cave at ‘eight’ and so on.

On returning to the schools later that year with the five-year-olds, the children participated in and listened to my new story Where Is Home?. They interpreted it with ease and were able to discuss maturely both distance, landscape and direction. The book provided a solid basis for me to jump into the more difficult concepts of compass points.

- Once the children understood the clock/compass on the ‘forest’ map/mat, they found using the dirty river mat quite easy.

- The children were able to communicate distance physically, using their arms, linking arms or in comparison to their classroom and playground.

- The five-year-olds were able to follow the river landscape on both maps and discuss the direction in which the river meandered using north, south, east and west without any problems and enjoyed the idea of the ‘bird’s eye view’ perspective.

- Two smaller groups of children understood the idea of northeast, southeast, southwest and northwest too.

- The children began discussing the characters of the butterfly, the octopus and the sea within the landscape. Jessica (5) said ‘If the sea is this big (holding her arms as wide as she could) then you wouldn’t see the butterfly or the octopus because they would be tiny. If the sea was as big as the playground you might just see them. In the story you can see the octopus and the butterfly because you only see a tiny, tiny, tiny, the tiniest, tiniest part of the sea so they look quite big. If you were in an aeroplane and looked down you see lots of sea but not the octopus and the butterfly, because they are so tiny.’

- Jessica and Sam, sitting on the dirty river mat and the octopus mat described the landscape. ‘So this river is like looking down from an aeroplane and the trees are like dots but look at your mat Sam, you are right next to the octopus so he looks really big.’ ‘Do you think he is really that size?’ asked Sam. ‘Well yes, he is as big as us’ replied Izzy. Izzy, moved to the forest mat. ‘The trees are bigger here and the river closer because we are nearer them, but look at the snake[s] in the desert they are bigger because they are closer to us and the sand is further away.’

This was quite an amazing discussion and it wasn’t confined to Jessica. The small group of children who understood the NE, SE, SW and NW directions were able to discuss this. Oliver picked up two blocks. He held one nearer Molly and one an arm span behind. ‘Which is bigger,’ he asked the group. ‘That one,’ replied Molly pointing to the one nearest her. ‘No, it’s not,’ whispered Dan, ‘they are the same, but the other one is far away!’.

I then took the book and the mats to the nursery school to use with three- and four-year-old children. There were similarities but marked differences in this younger age range. Where Is Home? was successful in that it created a slightly different reading each time the narrative was delivered.

- The younger children didn’t identify with the idea of the butterfly as a metaphor for a displaced child as expected. However, they were able to understand the concept of the landscape as the butterfly’s home, where the butterfly had lost her home because the trees had been ‘chopped down’ (Polly, 3) or ‘blown up’ (Jamie, 3) therefore deforestation and displacement was a concept that was recognisable to them.

- They were able to comprehend the idea of the butterfly going on a journey through various landscapes to find a new home and the obstacles she had to overcome.

- The children also had some sense of distance and landscape. ‘He had to fly a long, a long way’ (Evie, 3). ‘He had to fly over the water, and the sand and the town’ (Dylan, 3).

- The mats were introduced one at a time, starting with the dirty river mat. The children really enjoyed crawling along the river landscape. With some help they were able to discuss moving from one end to the other and in which direction the river might be flowing. When asked where the river started a number of the children pointed to the left-hand side of the mat because ‘it’s little’ (George, 3). Pandora (3) pointed to the right-hand side of the mat and continued, ‘that’s bigger, the water is faster’.

- The second forest mat floored the children initially but when Pandora started tracing the river landscape with her finger the other children were soon involved.

- Was this because she had identified the direction in which the ‘dirty river’ flowed, perhaps because we have a tendency to read and write left to right or a purely arbitrary decision? ‘The trees are here’ announced Pandora, ‘and the water goes here’. Pandora recognised the symbols for the trees in the landscape and there was much evidence of basic cartographic understanding and awareness.

- The children used a lot of vocabulary in describing elements of the landscapes on the mats. The final mat, escape from Octopus, created much excitement and to my surprise Pandora floored me again in her understanding of scale. ‘The octop … octopus, can eat the butterfly’. She was asked why? ‘The butterfly is little and the octopus is big!’. George, now on the mat, contributed. ‘… and the snakes’. The children had a very strong sense of large and small and with some development one could see how the five-year-olds in the first group had moved on to a primitive sense of scale.

Conclusion

One of my aims in this study was to enable children to understand the basic elements of landscape within cartography in making sense of their worlds, and that, with the right picture storybook, they could do that. Where Is Home? was fundamental in delivering the concepts of landscape through distance and direction. Whilst the younger cohort grasped the fundamental elements of these themes, the older cohort were able to discuss and develop their own theories about aspects of cartography and really had a surprising understanding of the selected themes.

The mats were extremely engaging. Their tactile nature, where the children could sit on them and trace and follow elements of the landscape were particularly successful. These will now become an extension of another project for an older audience, where a set of information artefacts examining cartography in a wider world landscape, will now form a series of six books for a UK publisher.

Ultimately this project highlights the need for a picture storybook which asks as many questions as it answers, and the wordless picture book designed for this project does this successfully. It is the combination of the cartographic picture-book maker as polymath in creating a strong narrative that incorporates maps and mapping as a core element of landscape. Because of this the child, the reader, has the chance to form opinions of the world, of the landscape in which they live from a very young age. The most important places on a map are the ones we haven’t explored yet but with a knowledge of cartography, of direction, distance and scale through the landscape, these places can be grasped at a very early age and become probable, conceivable, plausible, imaginable and ultimately true and real.

Works cited

Knight, Karenanne (illus. the author) (2014) Where Is Home?. IOE Press/Trentham Books.

Meunier, Christophe (2017) The Cartographic Eye in Children’s Picturebooks: Between Maps and Narratives. Children’s Literature in Education 48: 21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10583-016-9302-6.

–– (2013) Children’s Picturebooks: Actors of Spatialities, Generator of Spaces. https://lta.hypotheses.org/445.

––. (2014) Children’s Picturebooks as Cultural and Geographic Products: Actors of Spatialities, Generator of Spaces. https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01181072.

Place, François (2014) Traveler of the Imaginary. Bookbird 52: 4, pp.125–128.

Rosen, Michael (illus. Helen Oxenbury) (1989) We’re Going on a Bear Hunt. London: Walker Books.

Dr Karenanne Knight (academic, author and illustrator) is the author of The Picture Book Maker: The Art of the Picture Book Writer and Illustrator, published by Trentham Books/IOE Press in 2014 and contributor to A Companion to Illustration, published by Wiley Blackwell USA 2019; The Symbiotic Dilemma of the Children’s Picture Book Maker in a Polymathic World, published by John Wiley 2019. Her specialist field is children’s picture books where cartography, the creative process, the illustrator as polymath and typography form many of her many interests, which also include botanical and national history Illustration and medical and scientific Illustration. She authors and illustrates picture books for children and regularly writes papers for academic journals as far afield as Australia, Portugal and the UK. Karenanne Knight is often invited to speak and present her work at various conferences on a national and international scale. She divides her time between her academic work at Portsmouth University; writing reviews for various platforms and publishers; writing, Illustrating and designing children’s, adult and academic books; design and logo/branding work for festivals, commercial and corporate clients, and completing illustration commissions; residences and collaborations with clientele such as the British Army and Truro Cathedral, The Royal Ballet, Great Western Railways, the Rt. Hon. Dominic Grieve at the Houses of Parliament, and Buckinghamshire and Milton Keynes Fire and Rescue. She exhibits her work nationally and has pieces in collections worldwide.