‘Bears Can’t Live in Houses with People, Can They …?’: Raymond Briggs’ Picture Book The Bear

British-born author/illustrator Raymond Briggs’ picture books for children usually challenge the viewer in one way or another. While they can be humorous, they can also be uncompromising, and frequently blur the line between fantasy and realism. Certainly they invite total involvement. The grumpy old gent in Father Christmas (1973), the pleasurably disgusting Fungus the Bogeyman (1977) and the gentle and poignant The Snowman (1978) are but a few of Briggs’ memorable creations that remain ever popular.

Originally, by adopting a realistic approach with textured, broken pen strokes to create outline and form, twice Kate Greenaway Medal winner Briggs’ drawing style was more conventional than that with which we are familiar today, but his attitude towards his art has ever remained the same. In Artists of a Certain Line (Ryder, 1960: 51), John Ryder quotes Briggs as saying that right from the start he knew that his future lay in illustration rather than in drawing and painting, an important distinction because illustration is, essentially, literary. As such, he wanted the protagonists in his illustrations to be more than mere components: they had to think and feel. It is this literary approach that has made Briggs’ picture books so popular and memorable. One can feel that the human characters in them really inhabit their forms and the situations that they are in. Consequently, they ‘ring true’ and one can empathise with them. And so it is in The Bear.

The Bear is written partly in dialogue, and this gives the narrative a sense of immediacy, while those pictures that are wordless can invite the reader/viewer to assume a narrative role. The Bear, like the other picture books mentioned above, draws on the cartoon-strip tradition. Thus, Briggs (b.1934) obtains his effects by using comic-strip conventions, such as frame-by-frame sequences and speech balloons, and cinematic devices that include close-ups that very effectively contrast with distance shots. Briggs uses these devices to the full not only for their cinematic qualities, but also for their emotional and dramatic possibilities.

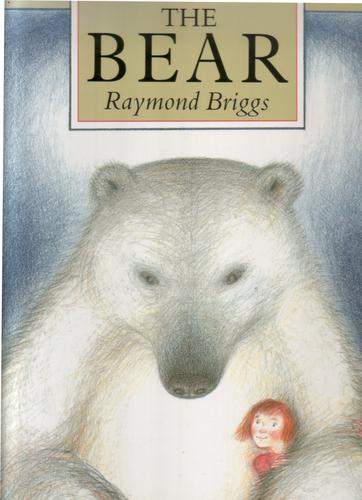

On the front cover of The Bear the animal’s massive bulk is established as are his huge paws with their sharp-looking claws that are accentuated by their overlapping slightly beyond the bottom of the picture into the cream border. This is a device that seems to bring the bear that much closer to the viewer. Beside the bear Tilly looks very small. Certain signifiers, however, serve to reassure the viewer and establish the nature of the relationship between the two main protagonists: Tilly’s facial expression, as she looks out from behind the bear’s paw, is playful, while the bear, with shoulders and paws relaxed, has a benign gaze that is directed down slightly in what might be a submissive gesture. Also, Briggs has chosen a shade of blue, a colour that can suggest affection and gentleness, to partly envelop both the child and the bear. Although within the picture book the animal makes direct eye contact with the viewer, his facial expression remains, as on the front cover, reassuringly gentle and rather passive.

The sequence of pictures that shows Tilly fussily cleaning up the bear’s pooh and wee, for he is not house trained, was going to be omitted from the animated version of The Bear, but Briggs felt that it was important to the narrative and insisted that it be retained. It gives the narrative a kind of earthy reality and makes the bear’s existence more believable so that we might accept the fact that both bear and child do exist amiably together. Yet Tilly is already aware of the bear’s elusive nature and that her hold on him is tenuous. She is in awe of the fact that her new friend is the ‘silentest thing’ she has ever known and like a ‘great big white ghost’ who ‘just seems to vanish like magic’. Tilly wants the bear to stay with her forever and ever but her mother reminds her that ‘he’s a long way from home’. These signifiers surely anticipate the poignancy of the story’s eventual outcome.

Through Briggs’ pictures and text the viewer/reader can be drawn into Tilly’s world and believe in the bear, as she believes in him. Tilly’s parents, however, cannot. Her father’s indulgent aside ‘Aaah! The wonderful world of a child’s imagination’ and the exaggerated nod-nod, wink-wink conspiratorial exchanges between her father and mother as they enter, not very convincingly, into the spirit of their daughter’s make-believe game, can seem irritatingly patronising. This is surely the response that Briggs wants from us.

The ending of The Bear is rather different from that of The Snowman (1978) because Briggs takes the viewer beyond a distressed child’s eloquent back view. It is, perhaps, no less effective for Tilly’s very emotional outburst when she finds that the bear has gone is not quite the end of the story. Her reluctant acceptance of her father’s explanation about what is real and what is unreal provides her, perhaps, with some kind of closure. Briggs takes the viewer, however, beyond Tilly’s limited experience and understanding and so he/she is placed in a subjective position. What follows is a very effective contrast of mood in which fantasy is replaced by a more realistic scenario.

Thus, the final page shows a sequence of seven small images that depict the polar bear returning to his natural polar home of icebergs and snow. Yet he seems to be a very different bear from the one with whom Tilly played, if indeed it is the same bear. He appears sure-footed and, from his vantage point high up on the edge of a huge iceberg, which is blood red from the glow of the now rising sun, powerful and muscular. Could it be that Briggs, echoing Tilly’s father’s explanation, is simply showing the viewer how a real polar bear behaves? Be that as it may, before continuing on his journey the bear does look back once, and it is for the viewer to decide whether or not he is recalling a little companion that he has left behind. The fifth small picture shows the bear swimming out in the icy water where another polar bear seems to be waiting for him. These are wordless, filmic images that can provide the viewer with a poignant and somewhat enigmatic ending.

While many of Briggs’ stories have a magical or fantastic quality, he is too much of a realist to give them happy endings: as he pointed out in a rare interview that appeared in the Christmas 2012 issue of the television magazine Radio Times, the ‘snowman melts, my parents died, animals die, flowers die … It’s a fact of life’. And, he might have added, a polar bear has to return home. Yet in The Bear, which has a narrative that is open to more than one interpretation, Briggs tempers some of life’s harsh realities with a sensitivity that beautifully addresses one child’s experience of love and loss. Thanks to Briggs’ marvellous imagination, the skilful storytelling, the rich imagery and the narrative’s subtle nuances, this is a picture book that the young and, perhaps, the not so young reader/viewer can enjoy and treasure.

In his provocative book Against Empathy, Paul Bloom argues that empathetic arousal is not the only force for kindness and that because of its narrowness and bias, and its insensitivity to numerical difference, empathy is a flawed basis for making decisions and a poor guide to social policy. He argues that certain activities must override empathy. For example, in order to be effective, medicine and the criminal justice system must ‘draw on a reasoned, even counter-empathetic, analysis of moral obligation and likely consequences.’

Bloom posits that ‘empathy is always perched precariously between gift and invasion’, and there is evidence for the warping impact of this dynamic in the competitive ‘enterprise’ funding of social care in the third sector. I have worked with organisations that are concerned with urgent need. Some of these organisations are focused on displaced people, such as migrants, and some on military veterans – themselves also conceptually displaced. These are people in pain and in great need. I find it distressing in the extreme to see these groups and their life stories pitted against each other for the provision of care. Even when resources are short, it is still unacceptable that the beauty-pageant approach demands a tally of empathy hits as currency. For me, and others working with the third sector, this is an example of relying on empathy to inform personal and collective decision making and social policy, and it is not good enough.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights was published in a picture-book form by my publisher, Frances Lincoln, in association with Amnesty International. It is a lovely book and I am proud to have been awarded it as part of my prize for the Diverse Voices Children’s Book Award. The text reads: ‘We are all born free and equal. We all have our own thoughts and ideas. We should all be treated in the same way. These rights belong to everybody, whatever our differences.’ As the text of the declaration makes very clear, these are rights. There is no requirement for these rights to be earned by engendering the requisite empathy to belong to, and be bonded with, groups with power. The declaration is unambiguous: society should be compassionate, just and fair because these are human rights and obligations, not because we feel warm and fuzzy and bonded. While acknowledging that empathy plays an important role in shaping responses, Bloom concludes that ‘being a good person is more likely to be related to distanced feelings of compassion and kindness, along with intelligence, self-control, and a sense of justice’.

And this brings me back to the versions of A Monster Calls and what they reveal about acceptable, relatable narratives – those that might more easily generate empathy – and, as a result, revealing what I consider to be its flaws as an adaptation. In the book, the monster has power beyond the boy’s imagination: it leaves traces of itself in the world, such as leaves and berries, that Connor must tidy up and hide. The book monster is personal to Connor, but it is real. It has compassion for Connor and great power but it does not cure Connor’s mother. The monster is ‘set walking’ to help Connor cope after his mother dies. The stories the monster tells are (it says) about life not being how you may think it should be or would like it to be. I suggest that the film tells a different story. Marketed to a family audience, it tells of an imaginative child provided with all the material – drawings, stories, wise grandfather and creative capacity – to imagine a monster. So the film monster who helps Connor is not coming to bring knowledge from outside the boy’s existing experience. The monster is Connor. Through his mother’s sketchbooks we see that in-extremis, Connor calls forth a version of what he already knows, including all the difficult stories-within-stories. This is, I suggest, reassuring for an adult audience who do not believe in magic or real monsters. It is reassuring because it tells a story that yes life is unfair and sad and unkind but actually it is just as it should be: the child, surrounded by thoughtful, supportive adults should and will be able to recover from great grief by accessing their own creative capacities and the embedded gifts of distributed good (enough) parenting. This is a story congruent with psychoanalytic theory. The story it tells is familiar and it is not disturbing. We can empathise with Connor and weep in safety because he is not really disrupting an adult sense of how things (probably) are and how they (probably) should be. Connor is looked after well enough and will be alright in the end, and he didn’t need any real magic to do it. This is the problem with asking empathy to do too much of the heavy lifting in the world. Empathy is a great and wonderful tool but like all tools its role is limited. Empathy is constrained by our capacity to hear the people and their stories that really disturb us and so it is constrained in the nature and variety of the problems we want, and need, to address.

Briggs, Raymond ([1994] 1996) The Bear. London: Red Fox.

–– (1973) Father Christmas. London: Hamish Hamilton.

–– (1978) The Snowman. London: Hamish Hamilton.

–– (1980) Gentleman Jim. London: Hamish Hamilton.

–– (1982) When the Wind Blows. London: Hamish Hamilton.

Ryder, John (1960) Artists of a Certain Line. London: Bodley Head.

Nodelman, Perry (1988) Words About Pictures: The Narrative Art of Children’s Picture Books. Athens, Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press.

Radio Times, 22 December 2012 – 4 January 2013, Christmas and New Year double issue; ‘Let it Snow’, Andrew Duncan interviews Raymond Briggs.