An Indigenous Reader (and Mom, and Scholar) Reflects on Classics

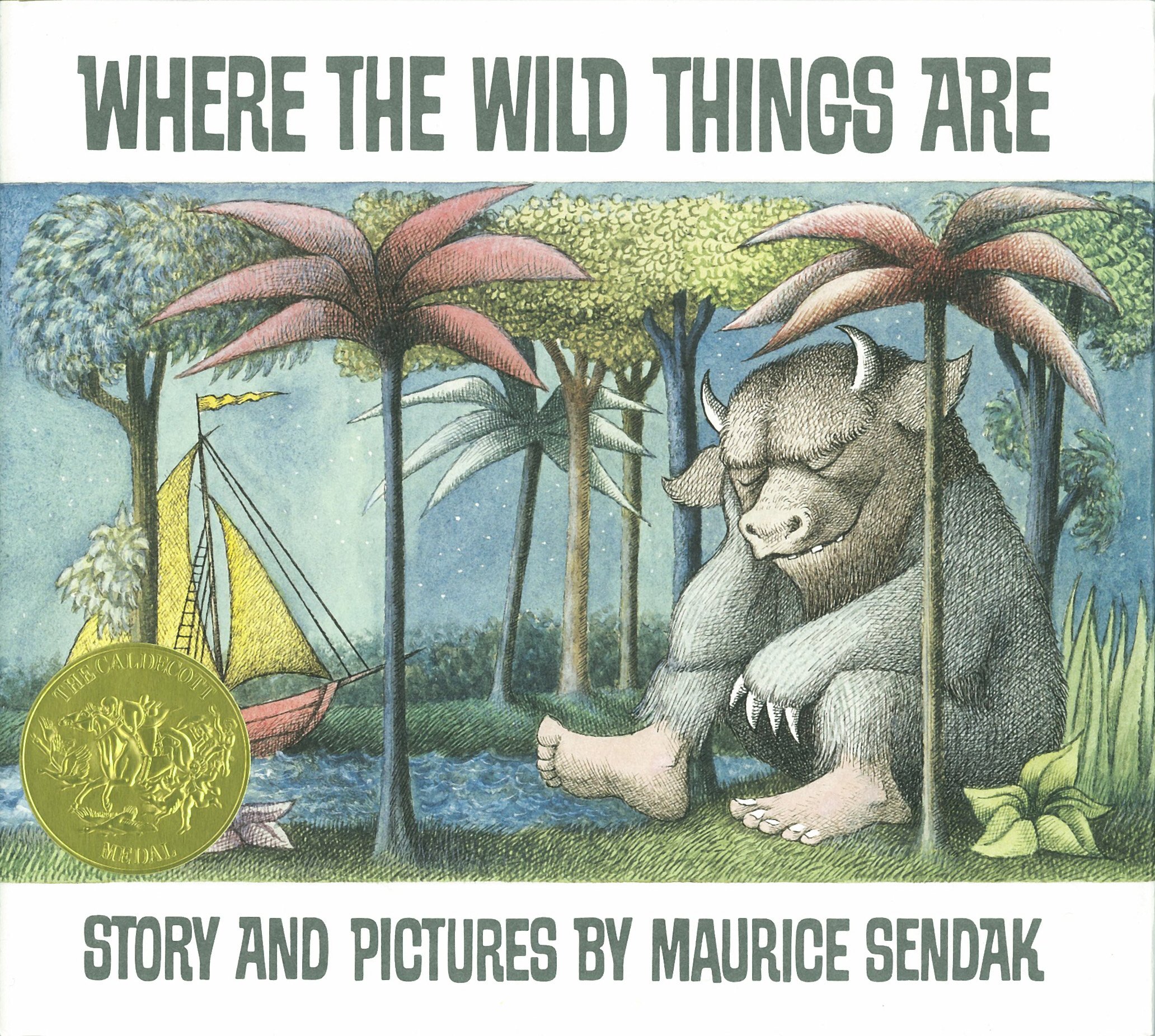

In countless books and articles by scholars in children’s literature, Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are is described as a classic. Published in 1963 by Harper & Row, Sendak’s book won the Caldecott Medal, sold millions of copies, and is the book that President Obama chose to read to children at a White House event. I love that he read aloud to children! I’m a book lover, too, but I don’t love Sendak’s book.

Those treaties are also why there are federally funded schools for Native children. You may have learned about Carlisle and Jim Thorpe from reading Sheinkin’s biography of Thorpe, Undefeated: Jim Thorpe and the Carlisle Indian School Football Team (Roaring Brook Press, 2017). The goal of these federally funded schools, established in the 1830s or thereabouts, was to ‘Christianise’ and ‘civilise’ Native people. In the late 1880s, the phrase ‘kill the Indian and save the man’ became part of the framework of the schools.

My family went to those federally funded schools. In 1964, I went to the Nambé Pueblo Day School. My father and grandmother went to it when they were children. Nambe’s day school opened in the early 1900s. By then, the government had stopped taking little children to the boarding schools hundreds of miles away from their homes. The schools weren’t well funded. We did not, for example, have a library. Periodically, the librarian from a nearby public school would stop by with a box of library books, but I don’t recall Where the Wild Things Are being in that box of books.

Some of the high schools had libraries, and taught the same sorts of book that were taught everywhere. I have no doubt that the literature taught in those schools included ‘classics’ like Louisa Alcott’s Little Women (Roberts Brothers, 1868, 1869). I wonder, though, how a Native child responded to some of the Native content in the book. Do you recall Laurie and the ‘Indian war whoop’ on page 201? Or the passage on page 251 where Jo wonders about an illustration of ‘an Indian in full war costume’?

I suspect I may have come across Where the Wild Things Are a few years later when my little sister went to Head Start. Head Start was part of President Lyndon Johnson’s well–funded ‘war on poverty’. I vividly remember the colourful blocks, child–sized play kitchen and the child–sized bookshelf, full of books. When (in time) I came across Sendak’s book isn’t important. What is important, however, is that I don’t like it! I don’t like Max. Or the wild things.

I never really sat down to think hard about why I don’t like the book, but last year, I saw something that made me sit right up.

That something is a t–shirt by Steven Paul Jones. He is a Kiowa–Choctaw artist, and creates the most eye–catching art. He takes something from pop culture and puts a Native spin on it. The t–shirt I saw was one in which he’d made Max into a Native child who is telling a story to a buffalo that looks much like one of Sendak’s wild things. In the word bubble over the Native child, there are two ships that look much like the Mayflower. Jones’s buffalo has a look of fear on its face.

Seeing that t–shirt, I wondered if, at some hidden place in my head and heart, I never liked the book because I saw Sendak’s Max as a European who had ‘tamed’ the ‘wild’ Indians he found when he got on his boat and sailed to that place where the wild things were.

In an interview, Sendak told Bill Moyers that he is Max and that the wild things are his Jewish relatives. Do the sketch and photograph tell us he had something else in mind, too? In the end, it doesn’t matter. Once published, books belong to the reader.

Those that garner ‘classic’ status carry a lot of weight. They’re in school and classroom libraries. Teachers and librarians read them aloud and do programming around them. Entire units are built around them. But so many of the books that become ‘classics’ are very White. Sometimes they – like Little Women – have content that denigrates Native peoples. Sometimes, their overall messages are not made explicit in word or illustration, but the content is there, discernible to some readers.

In the last few years, the publishing industry seemed to make a bit more of an effort to publish books by writers who are outside the mainstream in race, ethnicity and sexuality. Some terrific books written by them have won the major literature prizes. Not all prize winners achieve classic status. Will, for example, Matt de la Peña and Christian Robinson’s Last Stop on Market Street (Puffin, 2017) become a classic? What about Jacqueline Woodson’s Brown Girl Dreaming (Penguin, 2014)? Time, of course, will tell us if these books become classics. I hope they do, but they won’t get there without the help of parents, teachers, librarians and scholars in children’s literature. As gorgeous as they are in text and illustration, odds are against them. Too many people see them as books that aren’t meant for the White children in their classrooms or communities. Thinking that way is racist. Unintentional, perhaps, but racist nonetheless. People who think that way expect Native and Black children to read classics like Little Women and Where the Wild Things Are. I am not advocating for anyone to reject either one, but I do want people to think very hard about the books that they call classic so that the classics of the next 100 years are ones that are more inclusive of all children on planet earth.

Works cited

Alcott, Louisa (1868, 1867) Little Women. Boston, MA: Roberts Brothers.

Sendak, Maurice (1963) Where the Wild Things Are. New York: Harper & Row.

Sheinkin, Steve (2017) Undefeated: Jim Thorpe and the Carlisle Indian School Football Team. New York: Roaring Brook Press.

Matt de la Peña and Christian Robinson (2017) Last Stop on Market Street. New York: Puffin.