Getting Us Engaged! The Power of Biographical Picture Books

Diletta Donato

Biographical picture books weave their magic in so many different ways. They may sweep us up in the excitement of new research, evoke the past through the power of poetry, or even captivate us with obscure lists of naval equipment, maps and faded photos.

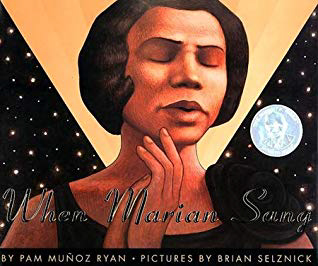

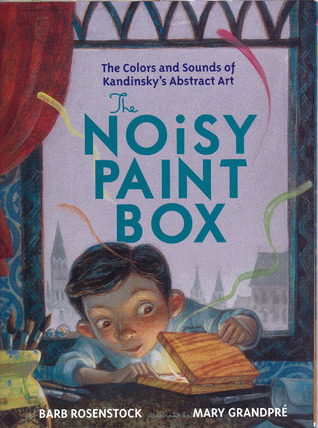

The two biographies I should like to share with you here are When Marian Sang: The True Recital of Marian Anderson (2002) by Pam Muños Ryan and Brian Selznick, and The Noisy Paint Box: The Colours and Sounds of Kandinsky’s Abstract Art (2014) by Barb Rosenstock and Mary Grandpré. These biographies are breathing, talking, living dramatisations of Kandinsky’s and Anderson’s lives. So although they depict historical events, they read very much like fictional picture books with beautifully rendered illustrations and scenes brimming with dialogue and action. Their other peculiarity is the paratextual sections at the end, which substantiate, complement and may even alter our reading of the texts.

When Marian Sang opens with two sumptuously illustrated spreads that transport us back to the turn of the century and the glittering Old Met in New York City. The curtain rises on a girl singing at a brightly lit window. We turn to the title page and, from the verso, we catch her glorious alto tones:

With one breath she sounded like rain, sprinkling high notes in the morning sun. And with the next she was thunder, resounding deep in a dark sky.

Then on the recto we read: When Marian Sang: The True Recital of Marian Anderson, libretto by Pam Muñoz Ryan and staging by Brian Selznick. In other words, through illustration, figurative language and the playful allusion to concert programme discourse, the paratext is framing this biography as an opera. This presentation of Anderson’s life as a stage performance is not just a wonderfully musical introduction to the text, it is also, and most interestingly, a clue to a practice that is displayed throughout the book, which is to call attention to the subjective, creative nature of writing and illustrating, even when these skills are devoted to producing works of non-fiction.

The sleek, hieratic elegance of Selznick’s figures harks back to the Art Deco style of the early part of the twentieth century, and the rich shades of sepia mimic the way photographs were printed at the time. So rather than claiming to provide a direct and objective view of how people and places looked, his illustrations remind us that an illustrator’s vision of the past is necessarily filtered through the photography and art of the period. This offers the reader/viewer a perspective that feels a few degrees removed from the historical events, and foregrounds Selznick’s mediating role in selecting, presenting and often re-imagining those events. We can observe a similar process in Ryan’s text. For example,

In order to address the era in which this story took place, [the author] has, with the greatest respect, stayed true to the references to African Americans as coloured or Negro. (p.40)

This, as she explains in her notes, is based on the singer’s autobiography My Lord, What a Morning (2002) in which ‘Marian Anderson referred to herself and others of her race in this manner’ (p.40). Rather than being disrespectful, this potentially controversial approach is aimed at constructing a narrative that is authentic to the Segregation Era, but, most importantly, by clarifying her reasons, Ryan is making herself visible as an author. As Joe Sutliff Sanders puts it in A Literature of Questions. Nonfiction for the Critical Child (2018):

Visible authors make explicit the fact that their ideas come from human sources, which, in keeping with the author’s intentions or not, makes stronger the possibility of engaging with a book critically. (p.59)

In this spirit the author’s and illustrator’s notes go on to explain the extensive research and the personal journeys undertaken in creating this book: the archives, trips and, most movingly, the encounters with people who knew Marian Anderson personally. This has the seemingly contradictory effect of both validating the historicity of their narrative, but also of presenting it as their own version of the facts. An important distinction thus emerges between two of the fundamental meanings of history: the facts that took place in the past and the telling of those facts. Therefore, by encouraging the reader to pick up on Ryan’s and Selznick’s creative and historiographical choices, these notes create a space where the reader can question the information provided and ‘become part of the process of intellectual inquiry rather than its passive beneficiary’ (Sanders, 2018: 12).

Further support in this sense is provided through a number of suggestions for museums to visit, books to read and recordings to listen to, thus opening the inquiry well beyond the confines of the book cover. In this way the interplay between text, paratext and peritext in When Marian Sang becomes a call to readers to undertake their own personal voyage into the life of Marian Anderson, and take on a co-creative role that will enrich and personalise the book with each re-reading.

The Noisy Paint Box is an exuberant celebration of art and creative freedom, and an inspiring example of the ability of the picture book to bring the past to life.

The first four pages swiftly sum up Vasya Kandinsky’s early childhood: he dutifully studies subjects he dislikes, plays the piano with the precision and exuberance of a ticking metronome, and relishes his parents’ dinner parties as much as the poorly cooked fish. No singular events, no memorable dates, no changes in season punctuate this iteration of propriety and gloom . . . until the day Vasya’s aunt gives him a small, wooden paint box.

Here the iterative time of Kandinsky’s ennui slows down to an almost real-time narration so that we feel like Kandinsky’s first encounter with painting is happening before our very eyes. Images zoom in on his wonderment, allowing us to peer into his paintbox, while variations in layout and font give voice to a polyphony of characters, colours and musical brushstrokes. As Kandinsky mixes the paints, we hear a whisper, then a hiss.

The swirling colours trilled like an orchestra tuning up for a magical symphony. (p.11)

Streaks of colour escape his paint box, roar across the gutter, and explode like fireworks across Grandpré’s double-page spreads; while Rosenstock’s text crackles with onomatopoeia, alliteration and similes, producing a kaleidoscopic eruption of colour, sound and motion. In this synchronic rendition of a few gleeful hours, Rosenstock and Grandpré harness Kandinsky’s synaesthesia (a neuropsychological trait in which the stimulation of one sense causes the automatic activation of another sense) so that we are not merely informed that he experienced colours as sounds, but WE do so as well.

Then the narrative speeds ahead: Kandinsky is now a young man studying law in Moscow. Years go by in one page, a decade in one page turn. We hurtle down the diachronic timeline of Kandinsky’s life eager to find out how he will ever put aside societal conventions and trust his artistic vision. A quote by the painter himself is printed on the copyright page and sums it up best:

I let myself go. I had little thought for houses and trees, drawing coloured lines and blobs on the canvas with my palette knife, making them sing just as powerfully as I knew how.

By the end of the book do we know more about Kandinsky and abstract art? Yes and no. We don’t know many dates, no titles of manifestos, or critics’ reviews of the period. However, we are alight with curiosity and open to abstract art like we have possibly never been before.

So we might even find ourselves humming spirituals, looking into modern-art galleries or noticing choices of discourse as we peruse the newspaper, for the magic of these biographies is in the engagement they inspire.

Works cited

Primary work

Ryan, Pam Muños and Brian Selznick (2002) When Marian Sang: The True Recital of Marian Anderson. London: Scholastic Press.

Rosenstock, Barb and Mary Grandpré (2014) The Noisy Paint Box: The Colours and Sounds of Kandinsky’s Abstract Art. New York: Alfred A. Knopf Books for Young Readers.

Secondary works

Anderson, Marian (1956) My Lord, What a Morning. Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Sanders, Joe Sutliff (2018) A Literature of Questions: Nonfiction for the Critical Child. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Diletta Donato is a passionate collector, writer and illustrator of picture books, She is currently doing an MA in Children’s Literature at Roehampton University, London. She taught English as a Foreign Language for 17 years in Italy and ran courses aimed at developing children’s learning skills through reading projects, acting and drawing. Alongside her teaching work, she has dedicated herself extensively to music and art, performing and recording on international concert tours with Vinicio Capossela and ensembles such as the Cambridge University choirs of Fitzwilliam College and Wolfson College. She is currently researching biographical picture books, and has recently given a talk on the topic at the 2019 IBBY UK conference in London.