A Puss without Boots: John Burningham’s It’s a Secret!

June Hopper Swain

The work of John Burningham has been defined as incorporating ‘postmodern strategies … to challenge expected reader/author relationships’ (Thacker and Webb, 2002:143).

And while the characters and situations in some traditional fairy tales might seem remote and the stories often lacking in humour, It’s a Secret! has an immediacy and playfulness that invites involvement. Thus, it is not a once-upon-a-time story for it is set vaguely in the present, and it is too grounded and unsentimental for there to be a completely happily-ever-after ending, yet it has several features that might be found in a conventional fairy tale. There is a talking animal and certainly the hero of the story, who guides the two children once they have mysteriously transformed themselves out of their everyday world into one that is more colourful and vibrant; but before this can happen there is a hazardous journey during which some villains give chase.

The cat in ‘Puss in Boots’ has a certain swagger, is wily and ambitious and gains fame and wealth, by whatever methods, for the story’s hero. Burningham’s puss in contrast seems modest and accommodating. He can talk, on occasions, but he knows his place when he is fulfilling his part-time role of family pet. Like most domestic cats he has another, secret, life but one that is surely more exciting. Children love a secret, and it is the promise of finding out what it is in this narrative that can propel the young reader forward.

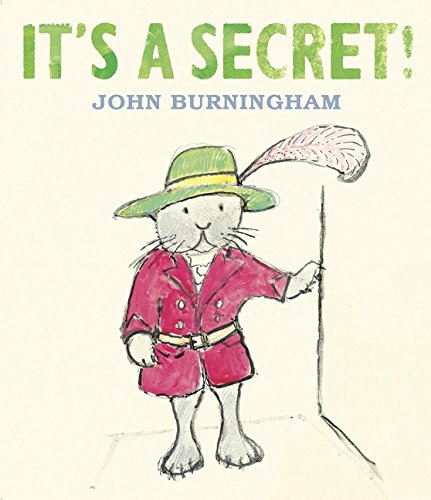

The picture on the title page shows a little girl, Marie Elaine, awkwardly clutching a cat. This is Malcolm, in his family-pet persona, passively putting up with his lot as best he can with a resigned expression on his face. This image is in marked contrast to the same cat, looking very impressive in fancy costume as described above, on the picture book’s front cover and who enjoys, it would seem, when he is not being the family’s pet, a busy social life.

Marie Elaine has long been curious to know where cats, especially Malcolm, go at night. When she finds Malcolm downstairs one night, therefore, dressed in his finery (and the cat bowl on the floor on his right can remind us of his double life) and discovers that he is going to a party, she begs him to take her with him. The mood of this exchange is low key, with Marie Elaine showing no surprise at finding the family cat transformed thus and having a conversation with him. Malcolm agrees to let her come to the party but insists that she wears party clothes and ‘getssmall’.

In response to Malcolm’s first request Marie Elaine rushes upstairs to her bedroom and returns wearing a fairy costume. His second request seems to be equally unproblematic, and here the text’s deadpan delivery states quite simply that ‘Marie Elaine got small’ and thus we see her in subsequent pictures. No apparent magic wand or talisman as there might have been in a conventional fairy tale. And here, perhaps, young readers might suggest how they think that it was done. And who could blame the amiable and sometimes put upon Malcolm if he feels, secretly, although this is not commented on in the text, some satisfaction that she has been, albeit temporarily, cut down to size.

Burningham uses a variety of media including collage and photographs in this picture book, and these provide interesting textural backgrounds for the scratchy, energetic pen and ink drawings and for the applied cutouts. These lively, often painterly pictures, uninhibited in execution and sometimes with a naivety that has great charm, drive the narrative forward.

While ogres enliven some versions of the traditional story of ‘Puss in Boots’, Burningham’s ‘baddies’ in It’s a Secret! are three particularly ferocious dogs that Malcolm and the children have to pass in order to get to the party. This episode provides a very effective double spread that shows the three dogs, anthropomorphised, loitering by some refuse bins on the corner of an alleyway. Two of the dogs, one of whom is leaning languidly against a wall, are in hooded duffle coats, the third is wearing a ‘beanie’ hat, and all three have their paws thrust deeply into their coat pockets. There are, surely, some visual puns at play here: in keeping with the hoody theme, the term ‘hoody’ having associations with street gang culture, two of the dogs have heavily ‘hooded’ eyelids; and there is, perhaps, a connection between the aimless youths ‘wasting’ time and the ‘waste’ bins and cartons around which they are loitering. This double spread is wordless and while it reflects this, as yet, passive, motionless trio, it can also invite the young reader to take up the narrative and so discover something of the interplay possible between picture and spoken word.

This shows the dogs, now appearing much larger, giving chase. Unlike Malcolm, they do not seem to have the capacity for human speech, and no longer being a parody of a gang of idle youths hanging around on a street corner, they have become, despite the clothes that they are wearing, a ferocious pack, the one leading them barking and baring its teeth. The text tells us that in making their escape Malcolm and his companions ‘rushed up the stairs’, and the jumble of lines depicting them thus conveys this. Poor Norman – oh, how we can empathise with him and thus become more involved with the narrative – is the last to mount the stairs and so closest to the pursuing dogs. It is his clearly drawn face with its alarmed expression, therefore, that we might focus on.

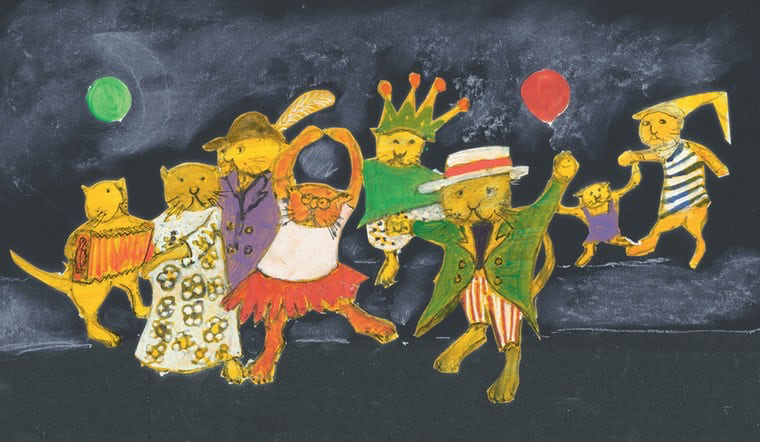

Of course, Malcolm and his companions do arrive safely at their destination, but not before they have had to escape the pursuing dogs via the rooftops, a crane’s rotating boom and down its lifting gear. No words accompany this very eloquent double spread. Drawn in loose, cursory pen lines that give their forms a lively, nervous energy, the three figures look small, isolated and therefore vulnerable, but not because of the dogs, who are now sitting, glum and ineffective, on a rooftop way below them, but because they are climbing down the crane’s lifting gear and hanging in mid-air. It is not difficult to appreciate the dizzying heights to which the trio has climbed, with the vast expanse of sky, which occupies much of the picture area, above them and the drop to the rooftops and, as we might imagine, the ground far below. But at last, with their ordeal over, the trio can anticipate the delights of the rooftop party that is about to start, and the cats already there welcome the children whole-heartedly and show them great kindness.

On their return journey, the trio, once again, make their way past the three dogs, but luckily they are now fast asleep. And these hooded ‘youths’ are not merely asleep but apparently totally soporific, having consumed what could be several cans of lager – or is it lemonade? The accompanying text does not comment, so viewers can draw their own conclusions.

The next morning, when Marie Elaine’s mother discovers her exhausted daughter, still in her fairy outfit, slumped on the sofa with Malcolm, now minus his costume, curled up fast asleep beside her, she comments in a matter-of-fact tone, ‘You look as if you were out all night with the cat’. Marie Elaine’s throwaway response is ‘I was’, adding ‘and I know where he goes at night’. But, of course, it was a secret so she couldn’t say where. Not, perhaps, the kind of exchange we might expect between a mother and her young daughter under similar circumstances in a conventional picture book. No anxious interrogation. No lecture.

Surely appealing to children and adults alike, John Burningham’s contemporary and witty fairytale-like picture book It’s a Secret! is imbued with generosity and goodwill, and has a restrained playfulness and pictures that sometimes speak louder than the words. Satisfyingly, Malcolm’s secret is shared with the reader/viewer who may hope that perhaps now Marie Elaine will treat Malcolm, as the family pet, with the utmost respect that he deserves – and that Norman will keep Malcolm’s secret too.

Works cited

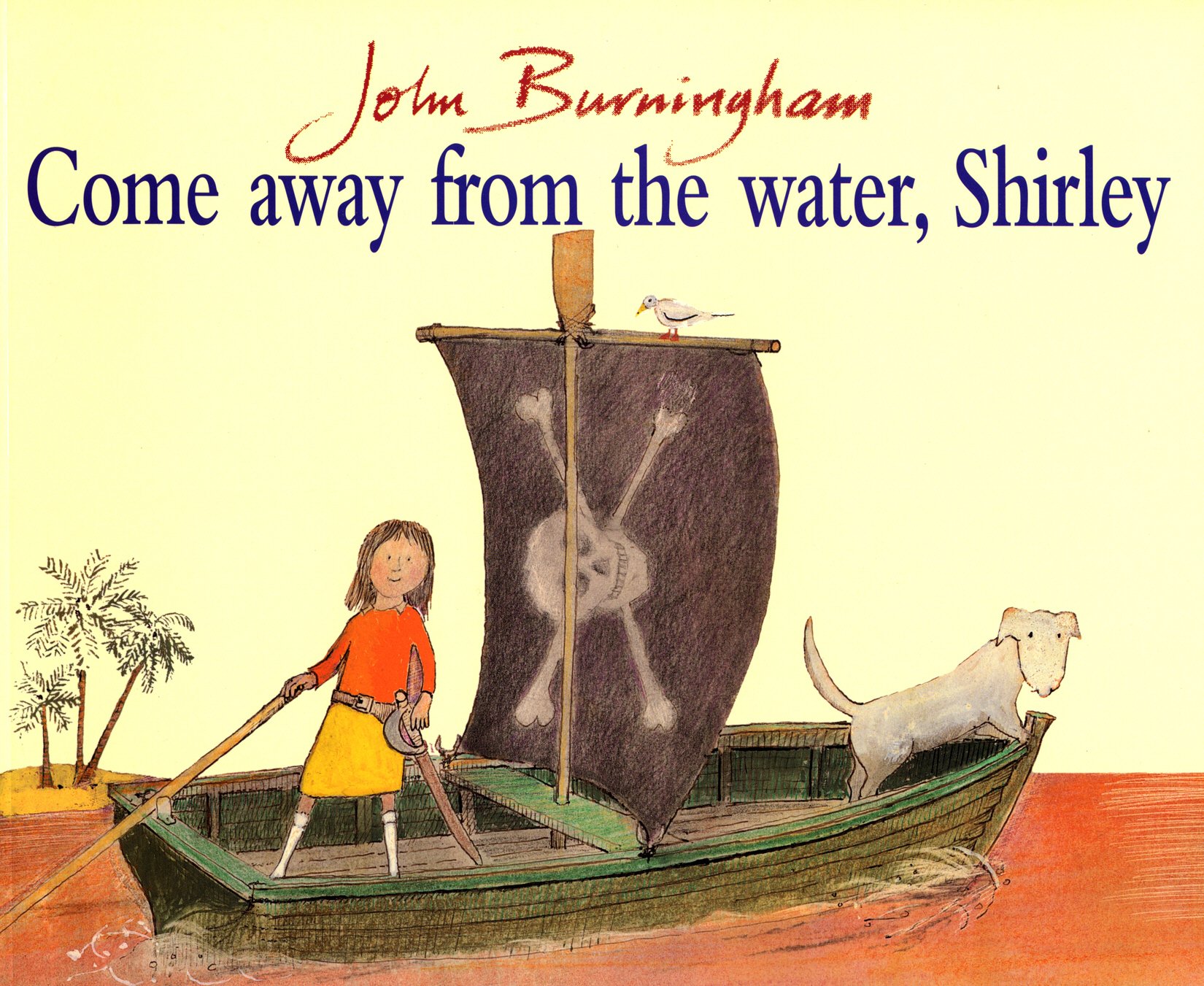

Burningham, John (1978) Come Away from the Water, Shirley. London: Jonathan Cape.

–– (2009) It’s a Secret!. London: Walker Books.

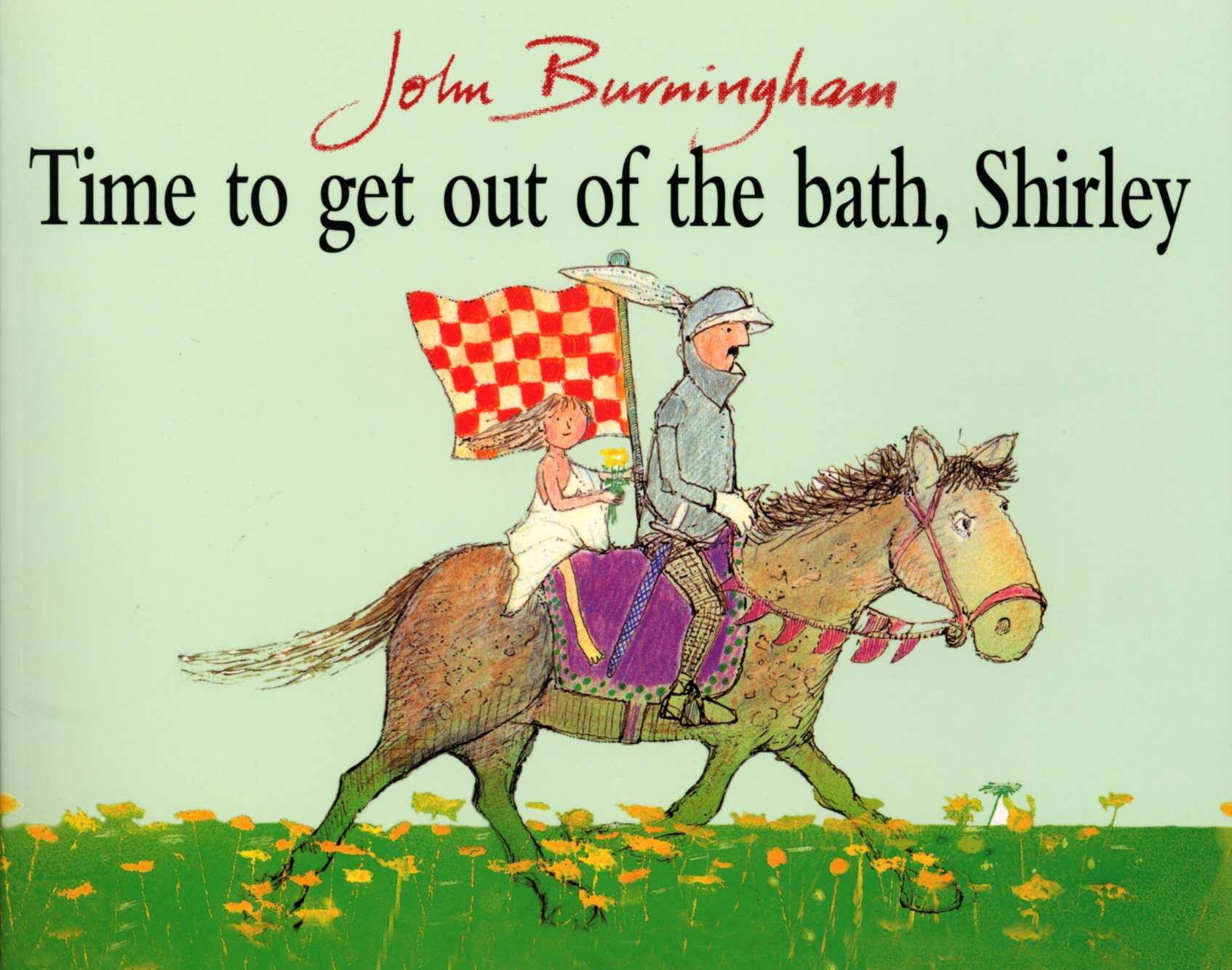

–– (1978) Time to Get out of the Bath, Shirley. London: Jonathan Cape.

Thacker, Deborah Cogan and Jean Webb (2002) Introducing Children’s Literature from Romanticism to Postmodernism. London: Routledge.