What Are You Playing At?

Anna McQuinn

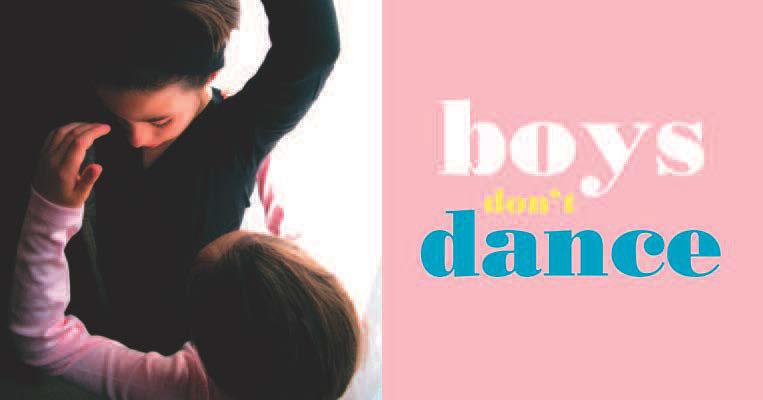

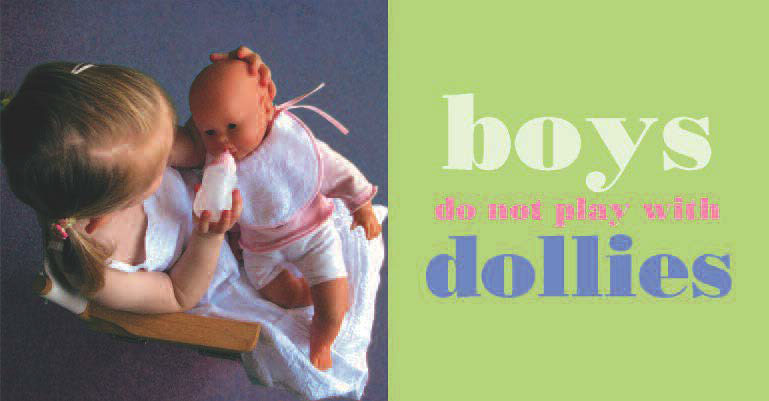

On a French stand at the Bologna Bookfair in 2012, I came across one of the most interesting books I’d ever seen. I’ve worked in children’s publishing since 1989, so that’s saying something! It took me a while to work out what was going on – my French is very rusty and was never brilliant in the first place, but I began to follow the structure and was blown away …. On the opening page there’s a photo of two young girls dancing and on the page opposite the words ‘Les Garçons ça fait pas de la Danse’. However, when you open the flap, inside you see two young men dancing with the comment, ‘ce serait trop ridicule!’. One might have expected some sort of resolution, but the next page was back to a young girl again, this time with the text declaring: ‘Les Garçons ça joue pas a la Dînette’.

Anyone who is familiar with the Alanna Books list knows that we don’t do ‘issue books’ in an overt way – though we deal with complex issues in our books. So for me this was a perfect fit. It robustly interrogates the idea that children should play in different ways according to their gender and does so without becoming in any way didactic. Many who would attempt to tackle such a topic would do so through the medium of a story – perhaps focusing on a young girl or boy who is told s/he is not allowed to play in a certain way because s/he is a girl/boy. The story would likely follow the child as they challenge the concept and, in the end, perhaps show her/him playing as they wish. Here, in comparison, the book seems to offer no such reassuring resolution. The text that accompanies the child image each time (which I will call the ‘child-image text’), robustly states that boys/girls do not X – as if it were a fact. There is no watering down or distancing – no ‘some people think …’ or other such panacea.

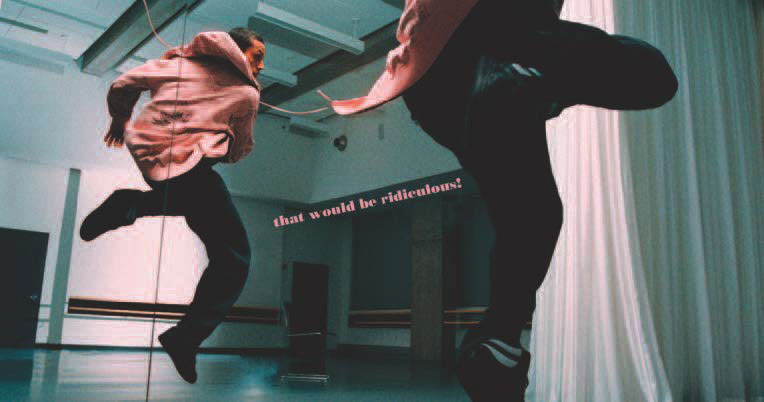

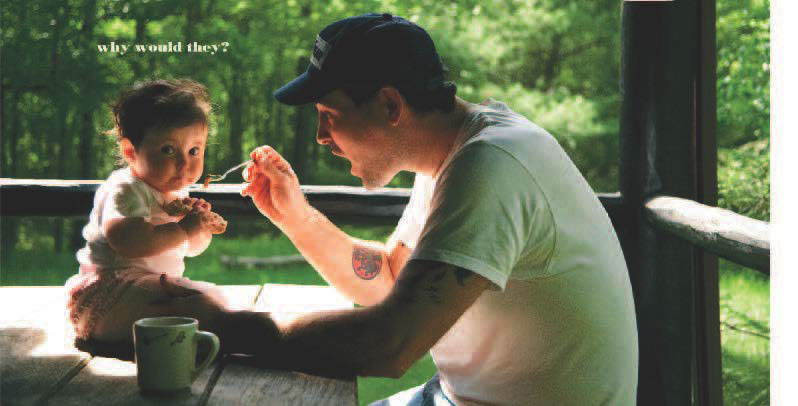

When you open the flap, the text accompanying the ‘adult’ image is equally challenging – seeming to underline or even amplify the child-image statement. It adds things like, ‘That would be silly’ or ‘real men/women don’t …’ However, when you look at the photo, the adult man/woman is doing exactly that thing that the text proscribes. So where does this leave the reader? And where does the meaning lie? The book opens with two girls dancing accompanied by the text, ‘boys don’t dance’. When you open the full-page fold out, the text underneath continues, ‘that would be ridiculous!’ But the photo image is of a young man in a dance studio pirouetting in front of a mirror. It’s a complex image – though he appears to be doing a pirouette, he is not wearing ballet costume. It looks like he’s doing modern dance and he’s wearing jeans and a hoodie, but the hoodie is pink. On the next spread, a little girl is playing with her tea set in her play kitchen. The text says, ‘Boys don’t play kitchens’. Under the flap, the text continues, ‘that would be silly, wouldn’t it’ – a rhetorical question, but the ‘wouldn’t it?’ is the first note of doubt we encounter.

Boys don’t dance. A young man in a dance studio pirouetting in front of a mirror

From here on, the reader anticipates a rebuttal to be revealed in the adult images under the flaps – rebuttals to the assertions that boys do not skip, and boys don’t show their feelings.

At this point the book switches to considering girls – and there is a similar progression from child text ‘girls do not play football’ continuing inside to ‘they really don’t like all that sweaty stuff!’ through ‘girls do not play with cars’ – ‘proper girls are just not interested in driving’, ‘girls do not build stuff’ and ‘girls do not fly planes’, this last accompanied by an image of a young girl in a rocket. And once again, the adult text, while seeming certain, is wholly undermined by the image.

Boys don’t play with dollies. A little girl playing at feeding her dolly with a toy bottle of milk

Why would boys play with dollies? A father feeding his young child

As I read the book at first and this realisation dawned on me, I was just blown away. It was just so clever! Instead of attempting to engage with or have any discussion about the stereotypical statements via narrative or challenging text, the adult photos simply show the statements to be untrue – blatantly so. This then prompts the reader to reach her/his own conclusion – that the stereotypes proposed by the text (regardless of how authoritatively presented) are simply not what happen in real life. For me, repeated readings led me to think of the text as the voice of societal censure. The voice that children hear in playgroups, in the park and even in their own homes – ‘Boys don’t play with dollies’, ‘Boys don’t dress up in tutus’, ‘Girls must look pretty, not get hot and sweaty playing games’ …. The photos don’t just challenge these views, they show the opposite to be true – how powerful is that!

The denouement is a wonderful image of a merry-go-round with a row of boys and girls playing and laughing together. For the first time (in the opinion of this reader) we get the voice of the child (versus the authoritative voice of censure) and the text switches from third to first person – ‘Actually, anything is possible! We can play what we want to play and be what we want to be! The world will still go round!’ Whereas up to now, the meaning has resided in the tension between the text and the images that undermine it, here the assertion is clear – that children’s play (and through it their vision of future possibilities) should not be limited by narrow societal gender norms.

It’s been three years since I acquired this amazing book and the possibilities it offers still leave me breathless. The clever yet simple device of the fold-outs and the use of the adult photos together pull off an enormously complex trick – that of addressing an hugely challenging topic in an innovative way which creates space for the child reader to make her/his own meaning. Instead of telling a child they have the right to play as they wish, the book shows the child a series of images that empowers them to reach the conclusion for themselves. In coming to reject the censorious voice of the text, child readers are empowered to reject any voice in society who would limit their right to play in any way.

What Are You Playing At? was reviewed in IBBYLink 41 Autumn 2014.

Roger Marie-Sabine (illus. Anne Sol, trans. Nathalie Jelidi and Anna McQuinn) (2013) What Are You Playing At?. Slough: Alanna Books. [First published in France as Á quoi tu joues? by Éditions Sarbacane in 2009.]