Tohby Riddle: An Advocator for Multiliteracies

This HCAA nominee spotlight is courtesy of Ann Lamont, in partnership with Evelyn Arizpe and the Erasmus Mundus programme, the International Master’s in Children’s Literature, Media and Culture (IMCLMC).

Tohby’s work is best summed up by its paradoxes. It can be soulful and funny; simple and complex, educational and entertaining. Always beautiful.

A Wide and Varied Output

Tohby Riddle has been nominated for the HCAA in his role as illustrator of children’s picturebooks. He began writing and illustrating children’s books in 1989 and has published in diverse genres. These include a YA novel, The Lucky Ones (2009); a grammar book, The Greatest Gatsby (2015); a history of the English language with Ursula Dubosarsky, The Word Spy (2008); a number of acclaimed picturebooks including The Great Escape from City Zoo (1997), The Singing Hat (2000), Nobody Owns the Moon (2009/2019), My Uncle’s Donkey (2010), Unforgotten (2012), Milo. A Moving Story (2016), Here comes Stinkbug (2018), The Astronaut’s Cat (2020); a non-fiction illustrated book with Ngiyampaa elder Peter Williams Yahoo Creek: an Australian Mystery (2019); his most recent work is with the 2020-2021 children’s laureate of Australia Ursula Dubosarksy, The March of the Ants (2021). Although he is also an accomplished wordsmith, this blog focuses on his qualities as an illustrator.

Picturebooks That Teach Us to Care

Recent work on cognitive science suggests that humans understand the world through anthropomorphising. The prevalence of animal characters in children’s literature then is a conscious narrative device to enhance children’s cognitive and affective development. Images can be a particularly powerful means of generating affective responses from readers since emotion and image are experienced instantly in the right hemisphere of the brain and then processed by the left hemisphere which grows in capacity as children mature. Even young children can interpret basic emotions represented in mouths, eyes and postures of characters (Nikolajeva, 2013), just as they interpret those embodied emotions in the real people they know and meet. By practising reading, children improve their theory of mind skills. (Nikolajeva, 2013)

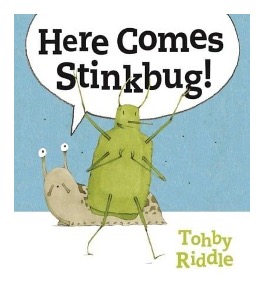

Riddle employs line drawing to represent his animal characters and their embodied emotions are rendered with humour and pathos. For example, In Here Comes Stinkbug! (2018) the smelly protagonist’s limbs signify his various emotional behaviours: lack of self- awareness, anger, sadness, assertiveness and finally a little more self-control. These images not only amplify the words of the text but skilfully help young readers to recognise and respond to basic emotions diegetically and extradiegetically. Stinkbug and his friends are beginning to negotiate the relations that govern playing with others and so the book becomes a safe space to begin thinking beyond solipsism.

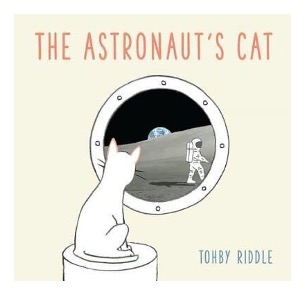

Picturebooks that present more ambiguous relationships through more complex interplay of word and picture can help young readers to explore more challenging social emotions. For example, in The Astronaut’s Cat the focalised narrative is disrupted, drawing attention to the multimodal nature of the text and the multi-layered emotions of the cat. We learn that the “inside cat….likes it like that” but, as the book progresses, the striking contrast between the cat’s vibrant dream sequence and the monochromatic moonscape of her existence suggests she is less content than she initially seems. The porthole effect frames glimpses into an alternative world and a potentially different set of relations between the pet and its owner who are often separated by the glass, a motif, perhaps, of their mutual isolation.

Picturebooks that Encourage Slow Looking and Deep Thinking

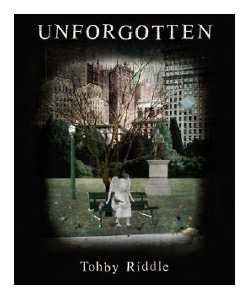

Riddle has said his work as a cartoonist has “trained” his “mind to wander and make unusual connections between things” (Hurst, M, 2019, 1). Unforgotten (2012) represents such reflective thinking in its form which embodies the multifaceted nature and significance of the picturebook genre.

The story concerns an angel that drops to earth and is dismayed, petrified even, by what it sees. Brought back to life by two children, a clown, a donkey, dog and a duck, it makes quickly for the heavens. These characters are hand drawn. In contrast, the fictional world of the city and its inhabitants are created using digital photographs from diverse sources. These include Riddle’s private life (his father’s journey across the Sahara in 1955 and his own photos from his local area and travels across the world), images from public archives (Library of Congress and NASA), allusions to fine art movements (French Symbolism) and popular culture (for example, graffiti, street signs, bill posters).

Riddle discusses the need to make these images cohere by superimposing global effects across each element to unite disparate elements into a habitable world for readers. The effect is fascinatingly immersive, enhanced by the tension between our expectation that photographs represent reality and the way that photo-fictions challenge us to reappraise what we think we know. Riddle’s use of collage and photo-montage in Unforgotten (2012) defamiliarizes the urban world creating as Druker (2018) suggests ‘a form of spatiotemporal fluidity’ (56) in which historical and contemporary, local and global co-mingle.

The visual allusions within Unforgotten (2012) are, I think, rich indeed and merit in-depth study. Photographs of existing public statues of historical figures like Captain Cook, images of real places such as Macdonaldtown and Woolongong allude to actual political, social and economic struggles and the ideologies of colonialism, globalisation, capitalism and environmentalism. Thus, texts like Unforgotten (2012) have the potential to extend the literacy repertoires of readers and shape a critical literacy stance towards creative works that recognises these are produced and understood within specific socio-cultural and historical contexts.

A Commitment to Children’s Visual Literacy

In drawing attention to the “symbiosis” (371) between literacy studies and picturebook studies, Arizpe, Farrar and McAdam (2018) suggest children need to be taught to understand how images work, to learn the terminology to describe how they work and receive training in the processes of reading them (375). Riddle uses his platform as a popular and successful author and illustrator to support the education of children as consumers and producers of visual texts.

He has been a former editor (2005) of NSW’s the School Magazine and ambassador for the magazine’s centenary (2016). His work is part of austlit.com, a literacy resource for educational professionals.

Riddle creates free teachers’ notes to accompany many of his books. He gives insights into how the images are created, discusses his inspirations and uses artistic terms and visual literacy terminology to support children acquiring the metalanguage to describe their interpretations and intentions when reading and producing multimodal texts.

In conclusion, Riddle is a creator of mesmerising picturebooks and, also, an advocate for children’s multiliteracies.

References:

Arizpe, E; Farrar, J; McAdam, J (2018). ‘Picturebooks and Literacy Studies’ in Kümmerling-Meibauer, B. & Taylor & Francis Group 2018, The Routledge companion to picturebooks, Routledge, an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, Abingdon Oxon.Chapter 35, pps 371-380

Druker, E (2018). ‘Collage and Montage in Picturebooks’ in Kümmerling-Meibauer, B. & Taylor & Francis Group 2018, The Routledge companion to picturebooks, Routledge, an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, Abingdon Oxon. Chapter 5, P49-58

Hurst, M (2019). Tohby Riddle: The Moon, Donkeys and Hairy Men. [Online] 2 April. Available at: https://www.thesapling.co.nz/single-post/2019/04/02/tohby-riddle-moons-donkeys-australian-legends (Accessed 29 August 2021)

Nikolajeva, M. 2013. “Picturebooks and Emotional Literacy”, The Reading teacher, vol. 67, no. 4, pp. 249-254