The Mennym Family

Susan Bailes

The Mennyms are a devoted, respectable family peacefully residing at No 5, Brocklehurst Grove in a modern British town, where they have been for 40 years.

They form a large household representing three generations. Their world is suddenly thrown into chaos when, one wet October morning, they receive an unexpected letter from Australia. A certain lonely Albert Pond has apparently inherited the house and is their new landlord. He wishes to meet the Mennym family and is planning to make a trip to England in late November. Grandpa Mennym groans ‘If he ever finds out what we really are I shudder to think what he might do.’

Sprung from the pen of Sylvia Waugh, a retired English teacher, this series of five novels: The Mennyms (1993), Mennyms in the Wilderness (1994), Mennyms Under Siege (1995), Mennyms Alive (1996) and finally Mennyms Alone (1996) all deal in one way or another with the Mennym family trying to avoid exposure. They form a twentieth-century extension of earlier doll tales but, unlike countless predecessors, these kapok and cloth dolls are life size, made by the house’s original owner, spinster Kate Penshaw, an extremely gifted seamstress.

They were living and walking and talking and breathing, but they were made of cloth and kapok. They each had a little voice box, like the sort they put in teddy-bears to make them growl realistically. Their frameworks were strong but pliable. Their respiration kept their bodies supplied with oxygen that was life to the kapok and sound to their voices. (The Mennyms, p.17)

Throughout, the Mennym family is central and we are made to consider the dynamics of family life and relationships as well as the ways in which various domestic rituals and traditions help bind it together. The uncanny nature of dolls leads to a consideration of greater issues concerning existence itself and what it is to be human. It is the author’s treatment of the relationship between doll and human which I have found particularly fascinating, and one which at times strains the credibility of the reader or is troubling and disturbing.

Another early clue suggesting the true nature of their identity is their names, which seem a little strange for humans. Sir Magnus and Tulip are the grandparents, Vinetta and Joshua the parents with their six children who remain the same age each birthday: teenagers brother Soobie and his twin sister Nuova Pilbeam, along with his other teenage sister Appleby, younger ten-year old twins Poopey and Wimpey, and lastly Googles, the baby. Included in the household is Miss Hortensia Quigley, who becomes the Nanny. These unusual creations only came out of their silence and took over the house after their maker died. In Kate’s workbox she had left a cache of money which was sufficient to provide for the Mennyms in the difficult period of transition between her death and their life. Over the years they had become a successful family unit, able to cope with almost anything. Kate’s property passed to her nephew, Chesney Loftus in Australia where he remained. He was informed that the Mennyms were his aunt’s ‘paying guests’ who wished to remain on as tenants in the property. Sir Magnus and Joshua signed a tenancy agreement and Chesney received monthly rent in line with inflation.

The Mennyms are completely aware that they are not human. By ingenious subterfuges and stratagems, they have successfully kept their existence secret and have hidden safely behind the drawn curtains of their house of Brocklehurst Grove in the centre of a square of private, large, detached houses with well-hedged gardens. Their home is ‘ideally situated, just five minutes’ walk from the shops on the High Street, but looking as if it belonged to a country village’.

Being rag dolls, they did not need any food. They did use heating to keep warm and dry. They found that they could see with their button eyes. Their felt ears proved successful at hearing and their mouths learned to open and shape words. Their brains, made of kapok were no worse, and in some cases much better, than many of the human variety. (The Mennyms, p.18)

The Mennyms had very soon realised that they would need a policy for survival in an alien world. Their first law was to have as little contact as possible with human beings. They are mostly confined to the house but when they do venture out, they wear glasses to cover their button eyes, brimmed hats and wrap up well, carrying a large umbrella, weather permitting. They cleverly learnt how to use a telephone and manage to open a bank account without actually going into a bank. Rummaging through Kate’s old desk, they discovered an agent to whom they pay the rent.

Grandfather Mennym is a patriarchal figure, presiding over this post-war, traditional, stable ‘middle-class’ family, summoning them all to conferences in his bedroom whenever there is anything challenging or threatening to their lives which needs to be discussed and resolved. As the most senior male in the household, he is described as Sir Magnus. He has a particular interest in the English Civil War and writes articles, which he sells, by post, to various newspapers and periodicals. His purple foot can be seen flopping over the side of his bed. Tulip, his wife, is ceaselessly active, quick and economical in her movements. She speaks rapidly and is purposeful. She has beautiful crystal eyes, pure white hair, wears a small pair of glasses and a blue-and-white checked apron. A skilful knitter, she has ingeniously created her own ‘tulipmennym’ label for Harrods and earns money selling her garments. Her daughter Vinetta is very much the traditional ‘Angel in the house’, described as ‘ever the busy mother’. Her domestic chores include keeping the windows of the house clean and washing the net curtains. She struggles with the twin-tub washing machine and her rebellious 14-year old daughter Appleby. Meanwhile her husband Joshua and the twins take care of the garden. Joshua has wiry, threaded grey hair and is the only Mennym with regular dealings with human beings as he is employed. One position is that of night watchman at Sydenham’s Electrical Warehouse on the other side of town but in walking distance as buses are too well lit. Along with gloves, he wears a thick overcoat and a cap well down over his brows. By walking around the aisles of shelves once an hour or so, switching lights on and off, he deters potential robbers and, at seven sharp, hands the keys back to Charlie. Another position he succeeds in is playing the part of Santa Claus at Peachum’s store before Christmas, suitably disguised.

Soobie is distinctive, mysteriously being entirely made from blue material. He has short-cropped navy-blue hair. His face is a lighter blue and his eyes silver buttons, and he initially wears a blue-striped suit and blue leather slippers. His sad mood is in keeping with his colour. Poopie has blue button eyes and a straight yellow fringe that touched the top of his eyebrows. Wimpey has the same pale blue button eyes and golden curls, tied up in bunches and satin ribbon, making her even more doll-like than the rest of the family.

All the Mennym family ‘played at living and developed talents.’ Their days are filled with ‘pretends’. Christopher Ringrose (2006) examines lying in a number of children’s texts and cites the Mennyms as ‘sharing the aesthetic dimension which involves consideration of lying’s relation to imagination, fantasy and creativity rather than morality’. Countless earlier doll texts show children playing with their dolls and pretending to have meals or teaching them lessons, for example the illustrated series about Josephine and her Dolls (1915) by Mrs H.C. Craddock, whilst the Mennyms pretend to have meals and imitate humans. The children have their own doll playthings, for example Poopie has his favourite Action Man doll Hector, Wimpey has her American doll which says ‘Would-you-like-a-Chocolate-Milk?’, Sir Magnus pretends to suffer from ‘the gout’ in his leg hidden by the counterpane, so Tulip places a wicker frame under the top sheet to protect the inflamed big toe. Vinetta prepares countless meals and pretend cups of tea for her husband Joshua. Vinetta comments:

‘It is not all pretend. We are real aren’t we?’

‘I think,’ said Soobie sarcastically, ‘therefore it is self-evident that I am. And at least I know what I am, which is more than the rest of you do. I am a blue rag doll, that God knows how, can think and move. I do not eat or drink. I don’t know what being hungry or thirsty means. I do not mix with human beings. And I know that Miss Quigley lives in the hall cupboard.’ (The Mennyms, p.48)

Miss Quigley’s situation reveals yet another layer of fiction and pretence. For much of the first volume she likes to keep up appearances, pretending to live in her own house in Thetherwick Street and visiting from time to time. At the end of each visit she officially says farewell to the family but secretly slips in by the back door and back to her cupboard.

The letter from Albert Pond, which begins volume one. is revealed to be a complete fiction created by Appleby, Grandpa’s favourite. Her intelligence and ingenuity are highly praised as she finds a way to save the family from Albert’s planned visit by writing to tell him that the family will be away at a christening in Manitoba. However, all is not as it seems; the family discovers the truth that she wrote the letters and chose Albert Pond after seeing his name written ten times inside the front cover of a book, Greenmantle, she had found in the cupboard under the window seat in her room. She had purchased foreign covers from a catalogue and had loads of used stamps. Appleby’s actions border on immorality as she deliberately deceives the entire family and runs away when she is found out. There is a positive outcome, however, as Pilbeam declares:

If you hadn’t told all those lies in the first place, I wouldn’t be here. I would still be asleep in the trunk in the attic. I could have been left there for another forty years. And Miss Quigley would still be living in the hall cupboard. It was only my time in the airing cupboard that made me realise how awful her life must have been. (The Mennyms, p.213)

Whilst clearing the attic to make a place for Miss Quigley as a member of the household, Googles and himself to spend time in, Soobie is startled to find his twin doll sister literally in pieces in a chest. The headless torso ‘dressed in a Fair Isle patterned jumper, and roughly fastened round its middle was an unfinished short, grey pleated skirt. Pinned to its chest was a label with “Nuova Pilbeam” written neatly on it.’ The head is nearby, wrapped up in tissue with

a pale face with thick black braids either side of cheeks that each showed a spot of unnatural red. Pink lips that had never yet moved were stitched in fine satin thread in a neat, compact blanket stitch. Arched black eyebrows surmounted long black eyelashes. But where the eyes should have been there was a blank, unseeing space. (The Mennyms, p.92)

Finding two black beads on metal pin stems Soobie fills the eye spaces. So the reality of the process of the Mennym dolls’ creation is vividly revealed and Pilbeam is lovingly finished. ‘Carefully, with the eyes of a needlewoman, Vinetta examined every part of her unfinished child.’ The coming to terms with a new sister is also handled with the sisterly relationship between Appleby and Pilbeam bringing the first volume to a triumphant conclusion and emphasising the benefits of sibling love.

The relationship between dolls and the human world is perilous. Throughout the series we are made to comprehend the vulnerability of the Mennym family. Early in the first volume, there is a frightening encounter for Joshua during a spell as night watchman when his material leg is eaten by a rat. He has a perilous journey home where it can be repaired. In the concluding chapter of the first volume, Appleby confides in her sister Pilbeam how terrified she was when three skinheads in leather jackets came into the shelter where she had been hiding. They swore at her and she ran off terrified in the dark, tripping over a little iron railing into the lake. She managed to crawl out, wet through and wriggled into some bushes where she slept. She had ended up after dark, exhausted, lying on a park bench to rest which is where Soobie had found her.

The tangible fear and dread of death for the Mennym family is never far away and is manifested in the dilemma Vinetta faces when her daughter returns home soaked through. The decision to bathe Appleby to remove all the dirt both inside and outside is a brave one and something Vinetta privately regrets and questions. Her daughter’s survival is uncertain and she remains in the airing cupboard for several months to dry out before she can re-emerge and join the rest of the family. The reader empathises with Vinetta and it is not surprising that Appleby wishes to discard the chair she sat on during her captivity as soon as she is released.

Ironically Albert Pond does exist and writes a letter which begins the second volume, Mennyms in the Wilderness. After seeing a vision of his Aunt Kate in which she begs him to rescue the Mennyms as their home is to be threatened with demolition, Albert becomes involved directly with the family. He provides them with an alternative residence, miles away in the countryside, ‘Comus House’ with its Miltonic association, whilst campaigns take place. The plans are overturned for the time being thanks to the protests masterminded by a neighbour, Anthea Fryer at Number 9, Brocklehurst Grove.

Soobie has a close encounter with death himself in Mennyms in the Wilderness when he is kidnapped by some boys who call him a

‘clouty doll’ to be a guy on their bonfire. Waugh alludes to the sacrifice of Sydney Carton in Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities (‘It is a far, far better thing that I do, than I have ever done; it is a far far better rest that I go to, than I have ever known’) when Soobie believes that he is to be sacrificed on the bonfire to save his family. ‘It is expedient for you that one man should die for the people . . ..’ He considers the situation:

If these intruders should find out that the house was home to a whole family of living rag dolls, there would be no end to the misery it would cause. Soobie remembered only too sharply how his grandmother had called him a freak. All Mennyms are freaks, for what is a freak but someone or something outside the norm? (Mennyms in the Wilderness, p.178)

Soobie is hidden away but one of the boys, Bill, sat him upright on a chair and treated him as a prisoner, calling him Carlos and taking him a white enamel mug and a tea plate. As Soobie is being wheeled in a barrow towards the bonfire, he recognises the petrol station and decides the only solution it to make a run for it. The boys gain on him but, fortuitously, Albert Pond rescues him as he drives into the petrol station. He calls out to the boys, ‘I am Frankenstein and this is my monster.’ Undeterred they persevere until Soobie bravely turns on them and threatens to crush their bones. He opts for replacement clothing, a dark blue tracksuit with white bands round the cuffs. When the Mennyms leave Comus House, Soobie waves to the boys hidden in the grounds and terrifies them, as they realise he was certainly no robot.

Unlike the Plantagenet small doll family in Rumer Godden’s The Dolls’ House (1947) the Mennyms can speak to one another but also directly with humans. They are independent and animate. Godden’s dolls are passive and are able to do no more than wish. As Margaret and Michael Rustin point out (2001), ‘The stories establish a boundary between the humans and the doll people, while nevertheless allowing the dolls to be sufficiently active in their own thoughts and feelings to be figures in a drama. The dolls depend on the children to be made and kept alive.’ In Mennyms in the Wilderness the drama is heightened when human Albert Pond spends time with them, visiting the house and moving them to Comus House for safety. In the penultimate chapter Albert spends Christmas with the family and Appleby observes ‘Albert Pond is falling in love with you’ to Pilbeam. She replies ‘Don’t talk rot. He is a human being. I am a rag doll.’ The seriousness of the situation involves Sir Magnus speaking with him to protect Pilbeam. ‘You do not belong here. Its will be much better for you and for us if you return to your own world and leave us to get along in ours.’ Albert disagrees as he believes the doll family has become part of his life and his Range Rover is useful to them. Tulip informs him that he must go away and forget them for Pilbeam’s sake. ‘You are a human being with a future in the world of human beings. You will fall in love and marry one of your own kind. That is the way of things. When you leave this house today you will forget that we exist.’ He does leave but impulsively kisses Pilbeam on her cheek as he says farewell. ‘The black button eyes that had learnt to see suddenly did something they had never done before. They cried real tears.’ The chapter concludes: ‘Pilbeam’s heart was soon mended. She was only sixteen. Pilbeam never forgot Albert, but the memory, oh the memory, was sweet.’

Interestingly we return to this topic of romance in Mennyms Under Siege, when Appleby decides to explore a relationship with a human neighbour. Visiting a record shop with Pilbeam, she attracts the attention of neighbour, 16-year-old Tony, and they carry on a clandestine courtship with secret letters. Appleby accepts a date to a discotheque. Dressed in second-hand clothing including a long black skirt with a deep fringe round the hem, a shocking pink top with long sleeves ending in a point and a richly patterned tapestry waistcoat along with her butterfly sunglasses and candy striped gloves, she is prepared. With her red hair flying she out dances everyone else on the dance floor. Tony was surprised to touch her and find her wearing cloth gloves but she excuses this saying, ‘I have to take special care of my hands because I am employed by a model agency to advertise creams and lotions. My hands have appeared on TV.’ As he steers her back to the dance floor she realises how late it is and, like Cinderella, suddenly abandons him.

The plight of the family in Mennyms Under Siege has disconcerting relevance to us today as we endure the impact of coronavirus and ‘lockdown’ measures. Just as we have been advised to remain confined in our homes to stay safe, so Sir Magnus dictates that the Mennym family remains confined to their home. The nosy human neighbours have caused him to fear discovery, in particular Anthea Fry of Number 9, who had offered Pilbeam a lift after her secret trip to the theatre. She was rescued in the nick of time by Soobie who pulled her jogging away.

There is every chance that Miss Fryer will speak to Pilbeam the very next time she leaves the house. Then what? And she may know by sight any one of us that is in the habit of going out into the street, for whatever reason. She is dangerous . . .. As I see it we must all stay indoors for a month or two, till Miss Fryer loses any interest she might have in the residents of Number 5. (The Mennyms Under Siege, pp.39–40)

The restrictions placed on the Mennym family allow Joshua to go to his employment but ‘non-essential activity’ must cease including Soobie’s jogging and shopping. Initially it is all done by Miss Quigley until she finds it too much to bear. Such severe measures understandably lead the teenagers to rebel so that after two months Appleby and Pilbeam visit the Sounds Easy record shop.

The consequence of not going out to the shops means that the family suffers financially as Tulip’s products and Sir Magnus’ articles cannot be posted or materials received, not unlike the current economic consequences of ‘lockdown’. All of this seems plausible and uncannily realistic but the event leading to the apparent death of Appleby strains credulity. After spending time in the attic, Appleby discovers a ‘forbidden door’ which the ghost of Kate warns her not to open. Like Pandora’s box, she cannot resist and in opening the door becomes lifeless.

And the more it pitted its strength against hers, the more of the wonderful light filtered into the room. It bathed the bare floorboards making the wood look precious as diamonds. Whatever this was it was another world and Appleby knew that it could destroy her own, no matter how beautiful it might be. Appleby was finished, failing in her attempt to put right the harm she had done. (The Mennyms Under Siege, p.177)

Later Vinetta is filled with Kate’s spirit and pushes with Appleby calling out, ‘ “Deliver us from the evil. Strengthen us again disaster. Forgive me. This will never, ever happen again.” The moment the battle ended Kate’s spirit was free to leave the attic and thus did life return to the rest of the Mennyms. For half an hour Kate had been Vinetta, Vinetta had been Kate.’

Mennyms Alone and Mennyms Alive require the reader to believe in the possibility of some mysterious power which transforms the family back into dolls, restored fortuitously to life at the beginning of Mennyms Alone. After the loss of their home, the family are moved to a shop and are kindly looked after by a shopkeeper known as Aunt Daisy. Her nephew, Billy Maughan, visits the shop and sees the family of dolls, recognising the girl doll from three years ago at Comus House. In the last volume his aunt looks round the room, ‘This was the home of her childhood, and these dolls, people, dolls, whatever . . . were hers by choice.’ She remembers Billy had told her about the blue doll and that it was alive. There is a dramatic encounter between Billy and Soobie when the truth is acknowledged by them both. ‘You tried to save my life once,’ said Soobie. ‘You cared what happened to me. I care what happens to you. Just sit and listen till I tell you the story of the Mennyms.’ Billy understands the Mennyms will move to a new home and live for ever but promises he will never say a word about this. As predicted, the family does purchase a new home with the money Tulip has deftly saved over the years. They move there secretly, so completing this family saga.

The first volume was awarded The Guardian Children’s Fiction Prize and was shortlisted for the Carnegie Medal. It created enormous interest in film and television circles but none of these plans came to fruition. Today, however, you can see the original manuscripts at Seven Stories. Other archive material includes a musical adaptation of The Mennyms written by Lyndsay Barnbrook as part of a Masters in Composition at the University of Southampton. A production of the musical was held at the university in December 2007. The file includes a copy of the play script; prints of three digital photographs of the cast and crew from the university production; a copy of the programme for the production; and a CD recording of the music.

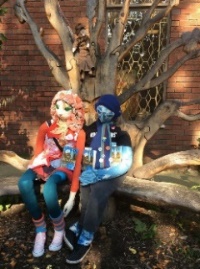

In conclusion it seems only appropriate that I should point out a direct link between the Mennym family and IBBY. The 22nd IBBY UK/NCRCL MA conference took place on 14 November 2015 at which the Ryde Mennyms themselves appeared and made themselves comfortable in The Portrait Room at Roehampton University. They had crossed by ferry from the Isle of Wight. Teresa Grimaldo explained how the figures had been made and the part they had played in the Ryde Arts Festival. The project had been about adults and young people creating and playing, and about how the characters invited interaction. There were many instances of townspeople relating in an amused and friendly way to the inanimate and potentially scary figures.

This photograph above in the margin shows a model of the spirit of Kate Penshaw in the tree above Pilbeam and Soobie. Unsurprisingly the number of Mennym book loans has increased in Ryde and further members of the family have been created including Miss Crocus and her dog, Brigstocke. Like Mary Norton’s family series of books The Borrowers (1952) the Mennyms will continue to inspire creativity and spark young readers’ imaginations provided they remain in our libraries for future generations and so live for ever.

Works cited

Primary works

Waugh, Sylvia (1993) The Mennyms. London: Julia MacRae.

Waugh, Sylvia (1994) Mennyms in the Wilderness. London: Julia MacRae.

Waugh, Sylvia (1995) Mennyms Under Siege. London: Julia MacRae.

Waugh, Sylvia (1996) Mennyms Alone. London: Julia MacRae.

Waugh, Sylvia (1996) Mennyms Alive. London: Julia MacRae.

Craddock, H.C. (illus. Honor C. Appleton) (1915) Josephine and her Dolls. London: Blackie and Sons.

Norton, Mary (1952 ) The Borrowers. London: Dent.

Godden, Rumer(1947) The Dolls’ House. London: Michael Joseph.

Secondary works

Ringrose, Christopher (2006) Lying in Children’s Fiction: Morality and the Imagination. Children’s Literature in Education, vol. 37 (pp.229–236).

Seven Stories Archive Hub, The Sylvia Waugh Collection. http://collection.sevenstories.org.uk/Dserve/Dserve.exe?dsqIni=dserve.ini&dsq App=Archive&dsqDb=Catalog&dsqCmd=Overview.tcl&dsqSearch=(((text)=%27 sylvia%27)AND((text)=%27waugh%27)).

Margaret and Michael Rustin (1987) The Life of Dolls: Rumer Godden’s Understanding of Children’s Imaginative Play. In Narratives of Love and Loss: Studies in Modern Children’s Fiction. Brooklyn, NY: Verso Books.

Digby, Judy (2015) The Ryde Mennyms: An Insider View of Parallel Session C. NCRCL blog for the 22nd IBBY UK/NCRCL MA conference ‘Steering the Craft: Navigating the Process of Creating Children’s Books in the 21st Century’. Conference held on 14 November 2015 at the University of Roehampton. https://ncrcl.wordpress.com/2015/11/25/the-ryde-mennyms-an-insider-view/.

Susan Bailes taught for 36 years and retired from a Surrey headship in August 2012. She was one of the early MA in Children’s Literature cohorts at Roehampton University and continues to carry out research. She values serving on the committees of IBBY UK and the Imaginative Book Illustration Society, is Chair of the Children’s Books History Society and regularly reviews books for these organisations. She has a particular interest in doll literature and all it reveals about the historical context in which it appears. One of her talks ‘Kathleen Ainslie (1858–1936): A Forgotten Female Edwardian Illustrator of Children’s Books’ was published in Studies in Illustration, no. 66, Summer 2017 and another was on ‘Fashioning Dolls: Different Treatments and Attitudes Revealed in Children’s Texts’ published in IBBYLink Spring 2019 entitled ‘Hobbies and Crafts in Children’s Books’, the theme of the 25th IBBY UK/NCRCL MA conference.