The Making of a Scottish Author

Theresa Breslin

One of my earliest memories is of ‘joining the library’ which, at that time, was a big old house in the local park near where I lived.

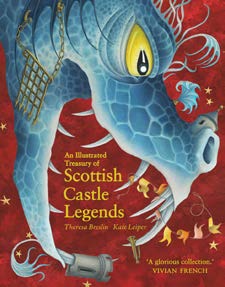

My hometown, Kirkintilloch, was a fort on the Antonine Wall – one of the furthest northern points settled by the Roman Empire. The fort was situated right next to the library, the highest part of the town. In the Middle Ages a castle was built on the same site. As a child, this sense of being surrounded by history exhilarated me, and looking at the artefacts left behind by our ancestors was fascinating. I imagined the Syrian archers shivering as they guarded the Roman Wall while snow blew across from the Campsie Hills, and the soldiers on the castle barricades peering down in the dusk at the campfires of their enemies. It was even more exciting when I learned that a bag of ancient coins had been found in the park! On my way to the library, I always kept a sharp lookout for the glint of silver or gold in the hope of finding a hidden hoard. I never did. But, when I look back now, I see that I did plunder a huge mass of treasure. Not crowns or precious jewels, but the books I browsed and borrowed to read. The non-fiction books took me, by word and picture, up mountains, through jungles and over oceans. I decided that when I grew up, I’d be an explorer and travel to these places. Fiction by authors such as D.K. Broster, George MacDonald, Alan Campbell McLean and Rosemary Sutcliff wrapped me in other worlds: stories of dragons and daring deeds, mystery and magic, and tales of kings and queens and castles. Looking back, I can see the direct influence which brought about such titles of mine as Across the Roman Wall (2005) and the series of Treasury books: An Illustrated Treasury of Scottish Folk and Fairy Tales (2012), An Illustrated Treasury of Scottish Mythical Creatures (2015), An Illustrated Treasury of Scottish Castle Legends (2019).

When I was in primary school a shining star which sent a shaft of light into my mind and my heart was the teacher who used the last hour on a Friday afternoon to share stories. No ‘Golden Time’ in those days! Instead of our modern schooling schedule where the last hour on a Friday is used for child-chosen creative pursuits we had this amazing teacher who would read out to the class, week after week, chapters from longer, more difficult books. When the book was finished, another fabulous adventure would begin. We were allowed to put our heads on our desks, to close our eyes and rest, and even the most hyperactive child would pause to listen. And so I fled through Highland glens with Kidnapped (1886) David Balfour and Alan Breck Stewart; explored a Treasure Island (1883) in the company of Jim Hawkins, Long John Silver and Ben Gunn; and jousted at tournaments in the castles of Ivanhoe (1890), greeting Lady Rowena and Rebecca – and many, many more. I’m sure this gave me a sense of narrative, of the musicality of language and embedded story structure.

In my secondary school we had truly inspirational history and English teachers who probably went off-piste in the curriculum. I was not particularly studious and dates in history eluded me. I was more interested in the stories. We were exposed to a wide range of literature, essays, plays and poems. Creative writing was encouraged with contributions to the school magazine, drama groups put on plays and pupils were taken on outings to the theatre. The experience of seeing Macbeth at the Citizens Theatre was an absolute highlight of my school life. Never did I dream that in the future I would sit in the same theatre and watch a theatrical production of a book I had written (Divided City (2005)). These activities encouraged and developed a life-long love of story, produced in all its forms.

My childhood home was full of books; non-fiction on every topic: history, biographies, science and geography, and also a wide range of fiction – e.g. Short Stories of Sherlock Holmes (1982) by Arthur Conan Doyle, Wee MacGreegor (1902), Peter Pan and Wendy (1911), and heaps of traditional folk and faerie tales, like The Well at the World’s End (1951), fables, myths and legends, stories of all kinds, plays and poetry. My father had a good memory for poems and would recite these to amuse his children.

I’ll tell you of the Ancient Gaels,

The ones the gods made mad.

All their wars are happy,

And all their songs are sad.

Being descended on one side of my family from a long line of Ancient Gaels I have a particular affection for stories and songs of doomed heroes and heroines. My siblings and I especially loved the more melodramatic ones, the contests of wits, the battles, the bravery, the stirring declarations, the noble deeds. I thrilled to the ballads and stories told to us by our parents. The family favourite, often acted out by myself and my brother and sisters, being ‘Lord Ullin’s Daughter’ by Thomas Campbell. Long suffering aunts and uncles were coerced into watching our presentation of the Highland Chieftain’s attempt to elope with his true love. Fleeing from the wrath of the girl’s father, Lord Ullin says:

And fast before her father’s men

Three days we’ve fled together,

For should he find us in the glen,

My blood would stain the heather.

Stirring stuff!

With my own recollections now on early childhood I realise the debt I owe to my parents and our extended family that I am familiar with the literature of my heritage, the great poetry of Scotland, from medieval anon texts to Robert Burns and Walter Scott.

I will be eternally grateful that, from an early age, I was imbued with narrative and a love of language, all of which has had a major influence on my work. Hearing first voices – primary voices – means that I am ‘informed by Scotland’ and thus as a writer ‘formed’ by its people, culture, geography, history, landscape and literature.

Works cited

Anon. Traditional Tales, Poetry and Ballads. Many at http://www.rampantscotland.com/songs/blsongs_index.htm. e.g. ‘The Twa Corbies’. http://www.rampantscotland.com/songs/blsongs_corbies.htm.

Barrie, J.M. (illus. F.D. Bedford) (1911) Peter and Wendy. London: Hodder & Stoughton.

Bell, J.J. (1902) Wee MacGreegor. Glasgow : Scots Pictorial Publishing Co.

Breslin, Theresa (2005) Across the Roman Wall. London: A. & C. Black.

Breslin, Theresa (2005) Divided City. London: Doubleday.

Breslin, Theresa (illus. Kate Leiper) (2012) An Illustrated Treasury of Scottish Folk and Fairy Tales. Edinburgh: Floris Books.

Breslin, Theresa (illus. Kate Leiper) (2015) An Illustrated Treasury of Scottish Mythical Creatures. Edinburgh: Floris Books.

Breslin, Theresa (illus. Kate Leiper) (2019) An Illustrated Treasury of Scottish Castle Legends. Edinburgh: Floris Books.

Burns, Robert. Poetry, e.g. (1968) Poems and Songs of Robert Burns, ed. James Kinsley, 3 vols. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Broster, D.K. (1925) The Flight of the Heron. London: William Heinemann.

Campbell, Thomas (1809) ‘Lord Ullin’s Daughter’. https://www.scottishpoetrylibrary.org.uk/poem/lord-ullins-daughter/.

Doyle, Arthur Conan (illus. Sidney Paget) (1982) The Adventure of the Speckled Band. Strand Magazine, February issue.

Gunn, Neil Miller (1951) The Well at the World’s End. London: Faber & Faber.

Linklater, Eric (1944) The Wind on the Moon: A Story for Children . . . Nicolas Bentley Drew the Pictures. London: Macmillan & Co.

MacDonald, George (1887) The Princess and the Goblin. London: Blackie & Son.

McLean, Allan Campbell (1955) The Hill of the Red Fox. London: Collins.

Montgomerie, Norah and William (1956) The Well at the World’s End: Folk Tales of Scotland. London: Hogarth Press.

Scott, Walter (1890) Ivanhoe. London: Cassell & Co.

Scott, Walter (1802) Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border. London: Cadell & Davies.

Shakespeare, William (first published in the Folio of 1623) Macbeth. London: Edward Blount and William and Isaac Jaggard

Stevenson, Robert Louis (1886) Kidnapped. New York and London: Harper & Row.

Stevenson, Robert Louis (1883) Treasure Island. London: Cassell & Co.

Sutcliff, Rosemary (illus. C. Walter Hodges) (1954) The Eagle of the Ninth. Oxford University Press.

Ann Lazim is the Literature and Library Development Manager at the Centre for Literacy in Primary Education, London, www.clpe.org.uk, which holds a large collection of traditional tales retold for children. She is a member of the IBBY UK committee, a previous Chair and was co-director of the 2012 IBBY International Congress.