The Importance of Place

Salvatore Rubbino

As an illustrator I spend my day drawing and thinking about pictures. My job is to interpret stories and create a visual world alongside the text, to complement the story and also to draw out its meaning.

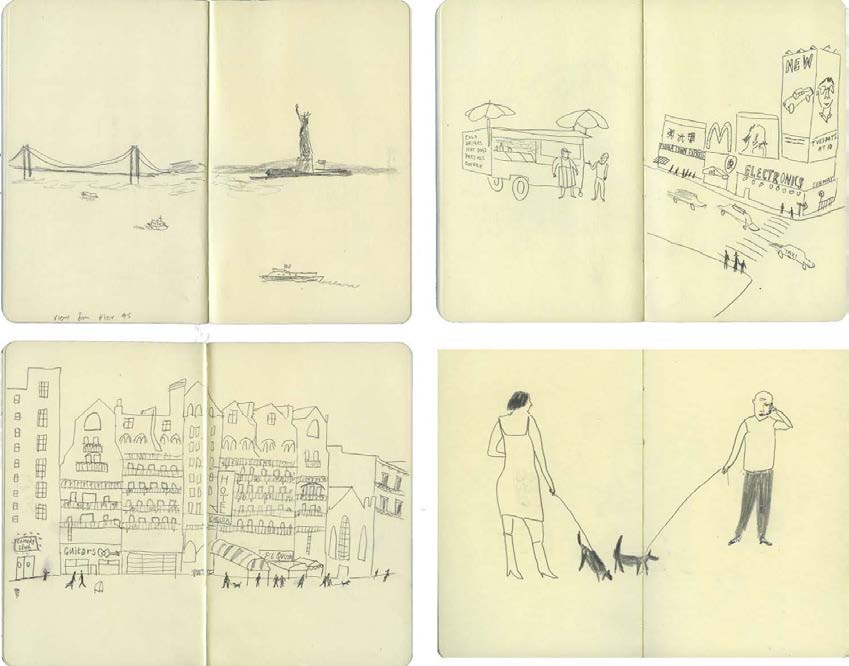

I’m frequently asked about where my ideas come from and although there isn’t any formula I can recommend, I do know that looking and drawing encourages ideas and helps me to work things out. I love to look in fact, looking is like a ‘visual meal’, it pricks my curiosity and feeds my imagination. I like to carry a drawing book with me wherever I go in case I see something interesting worth recording. The process of drawing helps me to notice things I would otherwise have walked past and overlooked and as a result makes me keenly aware of my surroundings.

Anything can be interesting and everything has visual potential; we are surrounded by ‘wonder’ but the challenge is training our eyes to see it. Writers read, musicians listen, artists look!

I grew up and still live in a busy metropolis. In many ways this has shaped my visual point of view and has become a vivid source that continues to inspire me. Cities recreate the idea of ‘landscape’ as a particular kind of urban spectacle. Full of drama and ‘visual friction’, large is placed next to small and historic next to new, tower blocks become geometric wonders of different shapes and patterns, buildings go up and come down within an ever-changing skyline as the city reinvents itself.

Cities are fluid and dynamic places and the thrill when I’m drawing in the street is that I’m never quite sure what will happen next. The judder of traffic and the flow of people will constantly rearrange themselves into new and exciting relationships for me to consider, into readymade compositions set against a background of building blocks. At the same time there’s often another layer of human-scale drama saturated with pathos and poetry, the homeless next to the happy lovers or an emphatic businessman on their phone whilst someone nearby wearing headphones sings a song. Images present themselves all the time, it can feel exhausting but it’s also wonderfully intoxicating.

Place helps to give a story an identity and a sense of belonging. It can create atmosphere and give the reader important cues about what kind of story they are reading. Place can reassure and tug the child reader into the story world with things they might also see and experience from their own lives (a park, a street or a school) or of course transport them to entirely new and exciting locations. Most importantly, place provides a stage-like setting for the characters in the story to perform on, struggle through sometimes, discover and interact with.

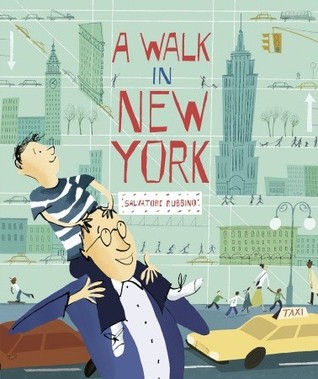

A Walk in New York was my first picture book and forms a short series which also includes London and Paris. The books are part story and partly a way to deliver fascinating facts whilst exploring the rich experience of urban life. Each title has its own set of characters who guide the reader on a virtual tour through the city; a route I carefully researched and walked to make sure it could also be used on location should a real visit take place. Not too arduous for young explorers (no more than four miles) which always includes a stop for lunch and a panoramic view of the city. There’s an annotated map at the front with the characters to suggest that the reader can see and experience similar things too.

Below are several drawings made on location in New York (Figure 1). I particularly enjoy this stage of research where the possibilities of what the book might look like are still quite open, I don’t have to make critical decisions yet and I’m free to soak up the city. I’m collecting different ingredients to help me understand – what makes New York, New York?

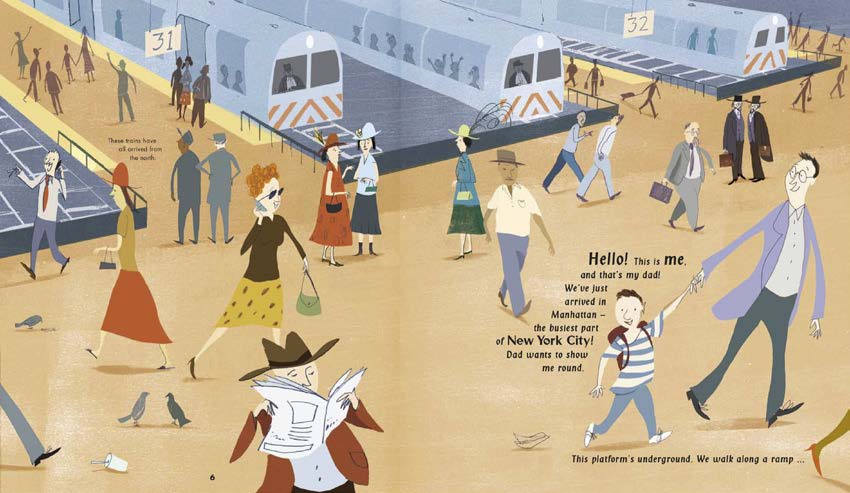

The job of the first page is to introduce the characters and the theme of the book. I wanted to convey the frenetic energy of New York and a sense of the people I remembered that make it so distinct (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

The character of the dad is loosely based on me. I’ve always wanted to be taller so reimagined myself as more dapper dad because of course anything is possible in a story! The boy narrator, in the striped T-shirt, is a version of my son (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

I work hard to recreate ‘believable’ moments and all the location drawings made earlier prompt me about city life. There are lots of details to discover (I’m rather addicted to detail!) – ladies gossiping, excited children …

Figure 3.

and friends re-united (on platform 31).

Figure 4.

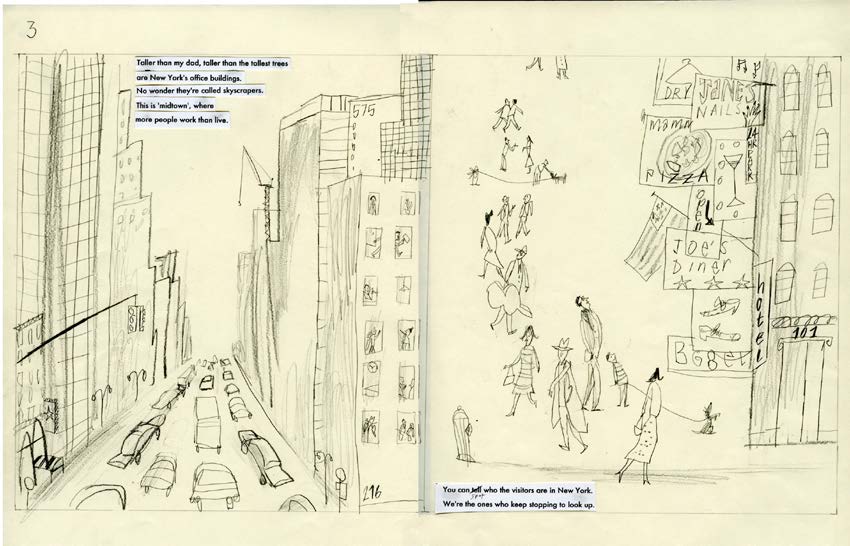

Once I’m feeling more confident and have a draft of the story I begin to put words and pictures together into a rough page layout (Figure 5). The theme for this page is ‘tallness’ and the gravity defying skyscrapers.

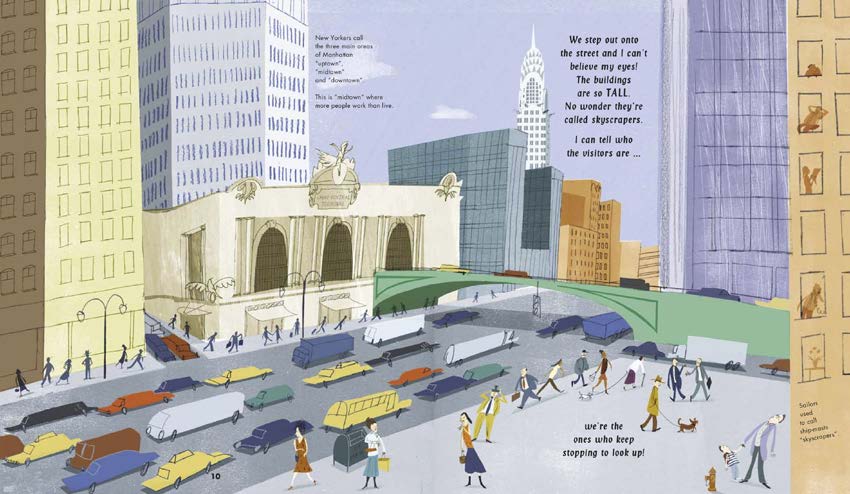

The same page was later transformed into a more coherent composition of buildings, traffic and people (Figure 6). There’s often quite a lot of changes until I tease out what I think the picture needs and how best to communicate the story. The boy and dad are straining their necks to look up and doing exactly what I did when I visited New York too.

Figure 5.

Figure 6.

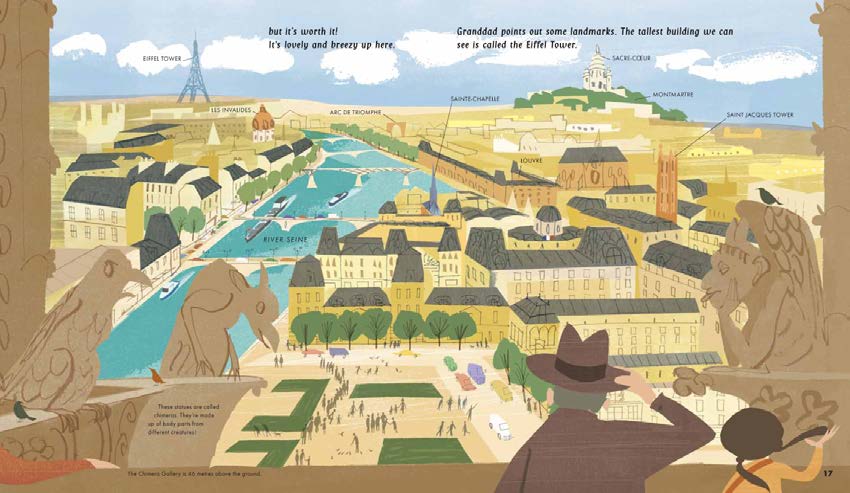

Unlike a conventional story construction where people and plot usually come first, the route had to be worked out in advance and the story structure fitted around this instead. In many ways, place is the real character in each of my city books. For A Walk in Paris, one of the challenges was finding a way to join up all of the places I liked. Some landmarks I could include and visit properly whilst others proved too far away. Although I did sometimes find a way, like Sacré-Coeur, shown on its green mound in the distance in a panoramic view (Figure 7).

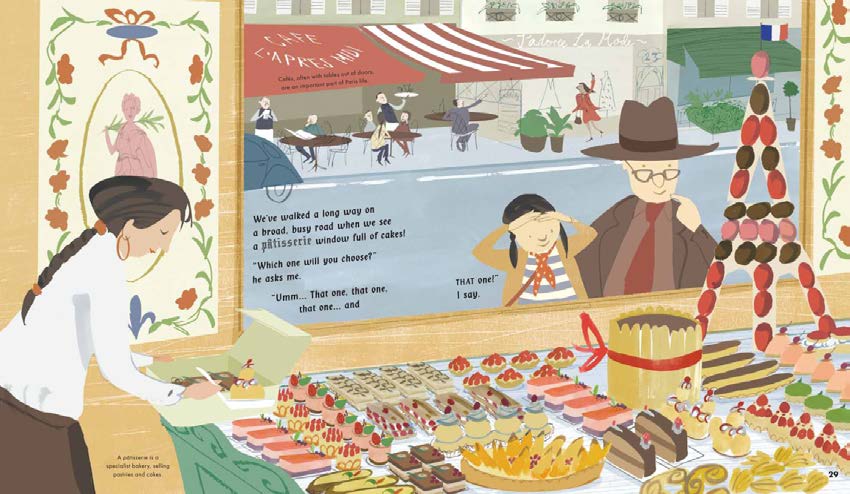

Paris is a visual feast, it delights the eyes and lifts the soul. There is a beautiful view everywhere you look! Even so, I was keen to find different ways to describe familiar landmarks and Paris motifs that can sometimes feel over familiar. The things that interest me are tangible moments – like when the characters from the story get lost in the district called the Marais with its network of maze-like streets (that happened to me) or when the girl in the book looks at the cakes through a patisserie window (I did that a lot too). Can you spot the famous landmark in Figure 7?

Figure 7.

These moments and others in the book attempt to describe what it feels like to experience Paris and its daily rhythms (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Some places however are beyond my reach like the location in the most recent story I have illustrated called Ride the Wind written this time by Nicola Davies where events unfold in a small fishing village along the coast of Chile.

Although I have a sensitivity to city scenes I can draw anywhere and respond to my surroundings even when there are no buildings in sight! Each book is like a stepping stone, a chance to experience something new and develop my picture making a little further. I’d certainly never drawn an albatross before I was invited to make pictures for Nicola’s wonderful story.

Most albatrosses live in the Southern Hemisphere, too far from my home in East London unfortunately to make a trip practical. There are however, taxidermy examples in museums that helped give a sense of their majestic wingspan and scale, although ‘my’ bird doesn’t open its wings until the end of the story.

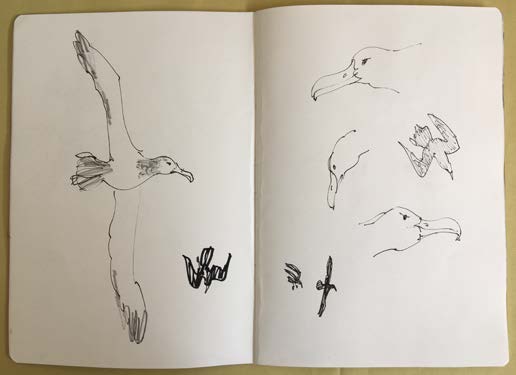

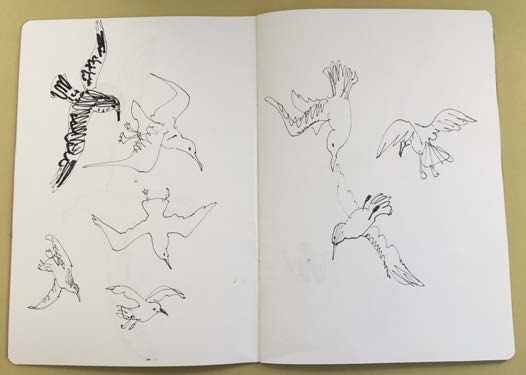

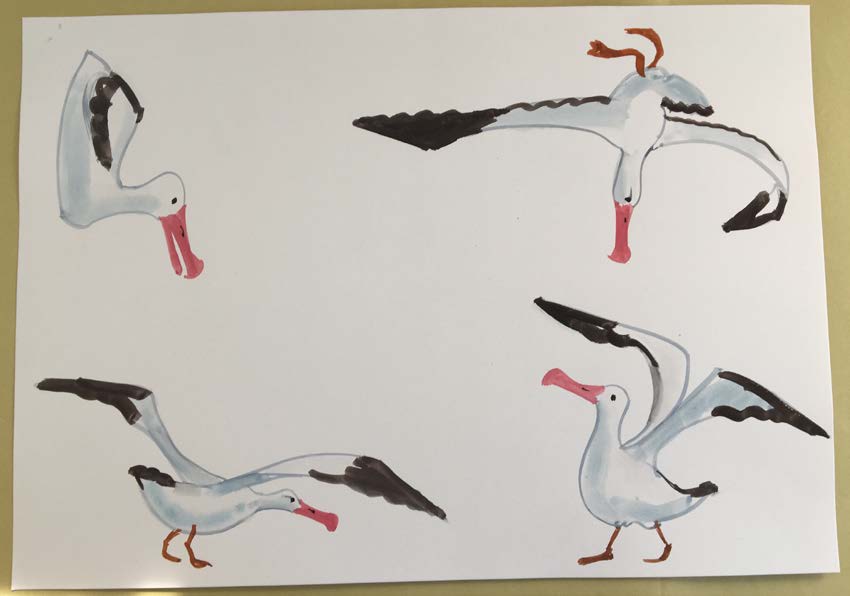

Without the chance to flex its wings I was worried that the albatross might look like a large goose so I needed other distinguishing features and discovered that they also have large hook-shaped beaks and strong-looking necks. I drew the albatross until I felt I knew it and also other sea birds from museum specimens and gulls whenever I walked along the River Thames (Figure 9 and Figure 10).

Figure 9. Early drawings for the albatross and other sea birds.

Figure 10. Practice pictures for the albatross.

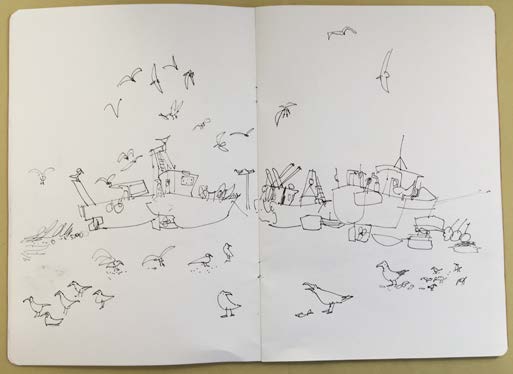

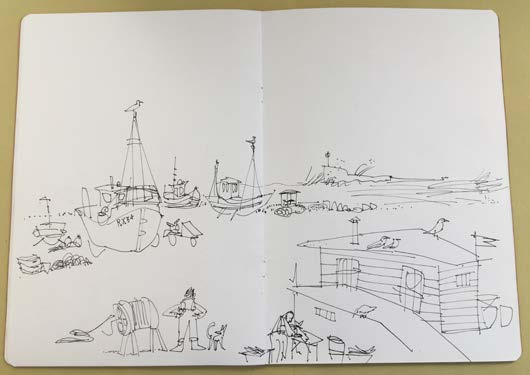

I wanted to experience sea weather and salt spray. I decided to take the train to Hastings rather than South America, to the ‘Old Town’ where the boats are launched from the beach and winched back in. It meant I could walk in between the fishing vessels, yachts and dinghies, draw their structure closely so I could describe them convincingly in the book and also experience something of the daily rhythm of hardy fishing people. They were maintaining nets, making repairs, gutting fish, whilst all around, piles of floats, impressive anchors, weathered fishing huts and even a local museum with a model of an albatross which I took as a good sign (Figure 11).

Figure 11. Location drawing at Hastings.

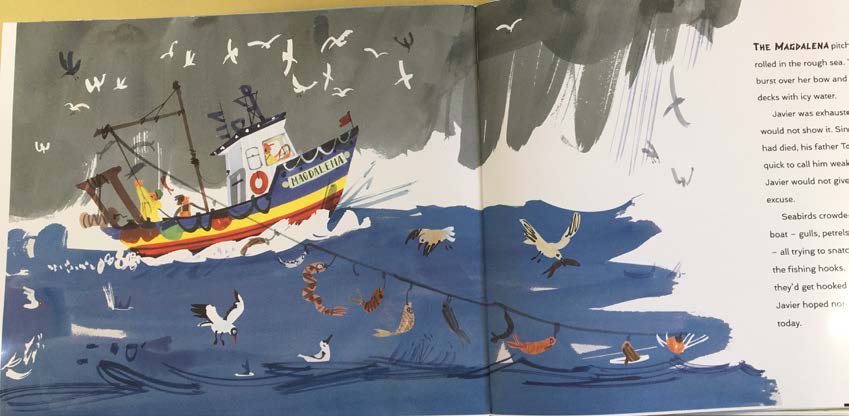

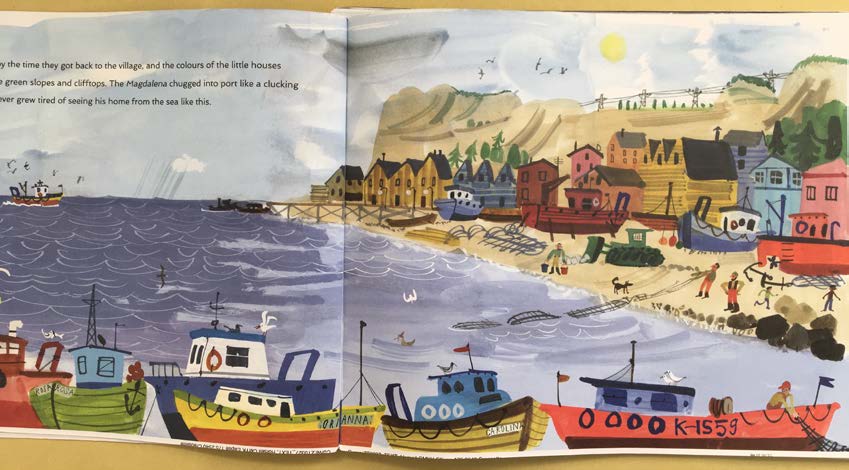

I borrowed the fishing huts and boats from Hastings for my pictures and transformed them with brighter colours, I made the coastline a little more rugged too. Although I had lots of printed sources and an archive of images online for Chile, my experience of walking along a real coast helped to fit things together. It gave me the sense of place I needed to charge the book with atmosphere, especially as a storm builds towards the end of the book (Figure 12 and Figure 13).

Figure 12. First page from the book.

Figure 13. The fishing boat arrives back to the village with Javier and the albatross, from the book.

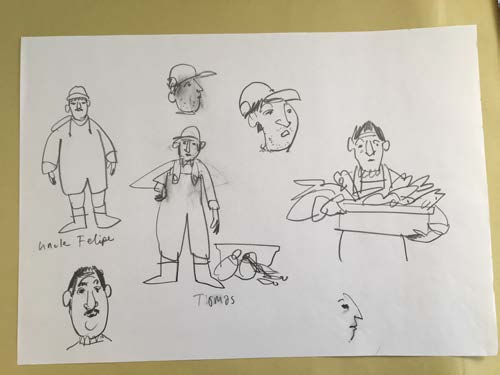

I see characters everywhere! On the London Underground, on the street, in the supermarket queue. I’ve never met a person I haven’t found interesting and we all come with a story. The characters in the book are a composite of relatives from Southern Italy I remembered from my childhood, farmers this time who had also been shaped by the weather and tough physical work.

I borrowed attributes from different people; there’s a little of me in the dad and a little of my son in the boy (Figure 14, Figure 15 and Figure 16).

Figure 14. Character sketch, Tomas the ‘strict’ dad, kind uncle Filipe and Javier, the boy.

Figure 15. Sketches for Tomas and Filipe, and Javier with the albatross.

Writing in September 2020 I sense that the pandemic has changed our experience of place. The freedom to travel we took for granted has been restricted. At times confined at home, the view from our windows was the only connection to the world beyond.

And then a strange thing happened, we became more aware of our immediate surroundings and appreciated them in new ways. Those lucky enough with a garden could sit and hear a concert of birdsong even in cities, no longer busy with traffic noise or the drone of aeroplanes. We have been thankful for parks and discovered the simple pleasure of a local walk. We became connected again to our surroundings in lots of small ways.

Figure 16. Javier smuggles the albatross home to help nurse it well again.

Place is important because we all need to belong. I hope these small acts of discovery and revelation continue. If you can remember to look with a sense of wonder!

Acknowledgements and works cited

Sketch and illustrations © 2009 Salvatore Rubbino from A Walk in New York.

Illustrations © 2014 Salvatore Rubbino from A Walk in Paris.

Sketches and illustrations © 2020 Salvatore Rubbino from Ride the Wind written by Nicola Davies.

All books published by Walker Books Limited www.walker.co.uk. All rights reserved.

Salvatore Rubbino trained at the Royal College of Art and has worked for many clients across different fields of illustration. A Walk in New York (2009), his first picture book, began as a series of paintings that was shortlisted for the Victoria and Albert Illustration Awards, and was followed by A Walk In London (2011) and A Walk In Paris (2014). These titles celebrate city living and the landmarks that make places special. He has also illustrated stories by other authors including Harry Miller’s Run (2015) by David Almond, A Book of Feelings (2015) by Amanda McCardie and most recently Ride the Wind (2020) by Nicola Davies. Salvatore Rubbino has taught at a number of art colleges and delivers events at schools, libraries and museums. He regularly works as a freelance educator at the Museum of London and at the Postal Museum where he creates activities and runs workshops helping visitors to engage with the collection. He has previously worked at the National Gallery and in 2012 created the family trail for the BP Awards at the National Portrait Gallery.