The IBBY Collection for Young People with Disabilities

Denise Scott and Leigh Turina

Everyone has a right to read. This is one of the primary tenets for IBBY. We would go further to say that everyone has a right to read in the format that best meets their needs.

We believe passionately in the right of children to have access to formats that allow them to read independently, where possible, rather than having the only access to the book be through another person. Since IBBY is all about bringing books and children together, let’s talk about access through language and formats.

What is language?

We talk to babies, to plants, to our dogs and cats. We wave to people over the road. We use facial expressions to make our points. Language is a system we use to communicate with other living things.

We work with the IBBY Collection for Young People with Disabilities, an international project under the IBBY Secretariat, and thus holding official status under UNESCO and UNICEF. Therefore, we may define languages slightly differently than some of you. Consider the definitions offered under the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities:

‘Communication’ includes languages, display of text, Braille, tactile communication, large print, accessible multimedia as well as written, audio, plain-language, human-reader and augmentative and alternative modes, means and formats of communication, including accessible information and communication technology.

‘Language’ includes spoken and signed languages and other forms of non-spoken languages.

Mirroring the IBBY National Sections, the IBBY Collection is a multilingual one. We have books in over 50 different languages, from Gaelic, Galician, German, Greek and Gujarati to Tagalog, Tamil, Thai and Turkish with large collections in French, Italian, English, Spanish, Japanese and Swedish.

But, how could it not be multilingual? Young people all over the world have disabilities and this collection reflects their stories as well as the formats they use for reading.

Not only do we have books in a multitude of written languages, but the collection also includes materials in other accessible languages, formats and systems: Braille, Picture Communication Symbols (PCS), easy-to-read text, tactile books and books with no text (silent books).

Accessible languages

Let’s look at printed communication systems which are not exclusively text based. Many of us have memories of sharing picture books with our babies and toddlers. For young, sighted children with no knowledge of the printed word, pictures are their first and preferred language. As we well know, they are reading their own story while you are reading the words.

For some people with disabilities the use of pictures as a communication tool continues throughout their lives. They may use them to interpret written text or to express their needs and thoughts. The Picture Communication Symbols (PCS) provide graphic symbols as an alternative and augmentative communication. These symbols are often standardised and generally include a word in simplified text alongside each symbol. (See Dracula below).

British Sign Language (BSL) is a visual-based language used by the deaf community. More than a communication system such as PCS, it is a language with regional dialects, grammar, syntax, classifiers, etc., just like spoken languages. British Sign Language has official language status in Scotland, England and the European Union, with minority status in Wales. However, it is not a universally used, international language. Many countries and areas around the world have their own unique sign languages. While there are books in the IBBY Collection in sign languages, many have fairly simple text. Sign languages are vibrant languages built with body movement and facial gestures in addition to the signs. They do not easily translate into a printed format and therefore are seldom the medium chosen for longer stories. In addition, it is important to remember that readers who learned to sign from birth may have difficulties when learning to read the printed word in, for example English, as it is their second language. (See David: Mission Possible below.)

Technology is changing everything around us. We often groan that these changes are not always good. However, for people with disabilities, technology continues to provide additional equitable access for reading independently. Technological advances, such as screen readers or automatic Braille displays, create new ways for some disabled people to access and interact with written material. However, there is still great value in the more traditional accessible formats like printed Braille and tactile books. We believe providing text in accessible formats is as important as providing it in a variety of languages.

Braille is probably the most common and well-known accessible format. It is an important tool for readers with vision loss to develop literacy skills and gain independence. Consider a reader who is blind and reads a novel in Braille. They can read at their own pace and control the way the story rolls out. Will they rush into the spooky scene or draw it out? In this way, accessible formats allow readers to create their own imagined version of the story.

Although listening to an audiobook offers a different type of reading experience, it, too, offers a measure of control. Not only can the listener control the volume, but they can also adjust the playback speed. Readers accustomed to the faster speeds of screen readers may choose to increase the playback while those with audio processing issues may slow it down. In addition, with the advent of voice controls and assistive switch technology, readers with limited movement can even browse and select their own books and operate all the control functions of their audio player, such as play/pause and fast forward.

The most popular books in the IBBY Collection are the tactile books, many of which are handmade by skilled artists. Everyone reaches out to touch these beautiful books when they are on display. Made with a variety of fabrics, papers, or plastic materials, they are designed to further engage the reader with the story through the sense of touch. Some books will include miniature three-dimensional objects, such as a small doll or a plastic spoon, while others will include abstract tactile representations, like a patch of fake fur to symbolise an animal. Learning to decipher tactile representations is an important skill for blind children working towards independence. (See Off to the Park! and Magico lnverno below.)

Wish list for publishers

For deaf or disabled people, having access to accessible languages and formats is essential. Despite this need, producing materials in accessible formats and languages is not always a priority for publishers. How can publishers begin to make changes? Consulting with the community is always best practice, but here are some tips to start:

- Often a change of the font type can make a book more inclusive. The publisher Barrington Stoke provides some excellent examples for readers who benefit from the dyslexia-friendly type font and other features. In general, some consider a san-serif font more universally accessible, but, either way, a discussion on the importance of font is worth having.

- A large print font improves accessibility for many children with low vision. It also benefits children with reading difficulties as well as those for whom books with small, dense print are overwhelming.

- Graphic novels can be a great option for those who benefit from limited text, or illustrations alongside text. However, they are often not accessible for readers with low vision or certain reading disabilities. Consider the text size and font used in speech bubbles.

- In addition to Braille and large print, children who are blind or have low vision benefit from tactile illustrations, particularly in picture books. This is also true for children with certain learning or developmental disabilities. Tactile adaptations are most effective when they are kept simple and highlight only the key elements of the illustrations, rather than every detail.

- Dual languages or alternate formats in the same publication, such as Braille or PCS alongside printed text, allows for a more inclusive, shared reading experience. A parent with a disability is able to read to their child, and children with different access needs and can read together. It is also a way of introducing the concept of diversity and equal access to all readers.

- Where possible, books should be ‘born accessible’. It is more inclusive and effective to design books with accessible formats in mind right from the beginning, rather than trying to adapt or revise them afterwards. However, materials that are not born accessible can and should still be adapted after the fact. In addition to creating e-book and audiobook formats, another option is to add sign language and image descriptions using video and audio files, respectively, made available by using a QR code or website.

Examples

One of the benefits, nay, joys of the IBBY Collection is to see outstanding examples from all over the world in accessible formats. The glorious books, created by authors, illustrators and publishers working to provide stories, books, and information in increasingly diverse formats, are astounding.

Here are some examples. The bibliographic information includes the year each item was published in the IBBY Collection of Outstanding Books for Young People with Disabilities catalogues so that you may look online for annotations and more information. See www.tpl.ca/ibby or https://www.ibby.org/awards-activities/activities/ibby-collection-for-young-people-with-disabilities.

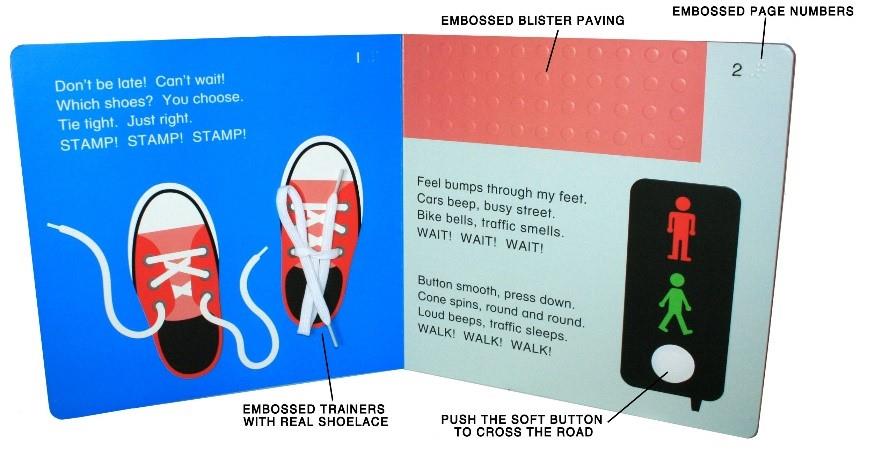

Child’s Play (text), Cheetham, Stephen (illus.). Off to the Park! Swindon, UK: Child’s Play International Ltd., 2014. ISBN 978-1-84643-502-7 (2015 IBBY catalogue)

Example 1

This book incorporates tactile and interactive elements, plus bold, large print and onomatopoeic language to emphasise movement and to engage readers.

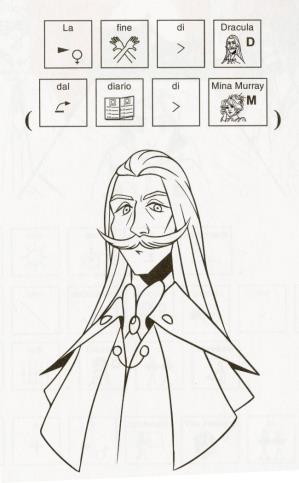

Stoker, Bram (original text). Coop. Accaparlante, Assoc. Arca-Comunità L’Arcobaleno onlus (adapted text). Dracula. Molfetta, Italy: Ed. La meridian, 2018. ISBN 978-88-6153-657-9 (2021 IBBY catalogue)

Example 2

Dracula is a graphic novel in PCS and simplified Italian. While most books using PCS are designed for young children and beginning readers, this title is intended for more advanced, teen readers. The original text and story of Dracula was adapted in collaboration with readers who are the book’s target audience. Inclusion in the creative process should be guided by the principle: nothing about us without us. This publishing group believes emphatically that classics can and should be adapted for all cognitive levels and includes an adapted version of The Diary of Anne Frank amongst its titles.

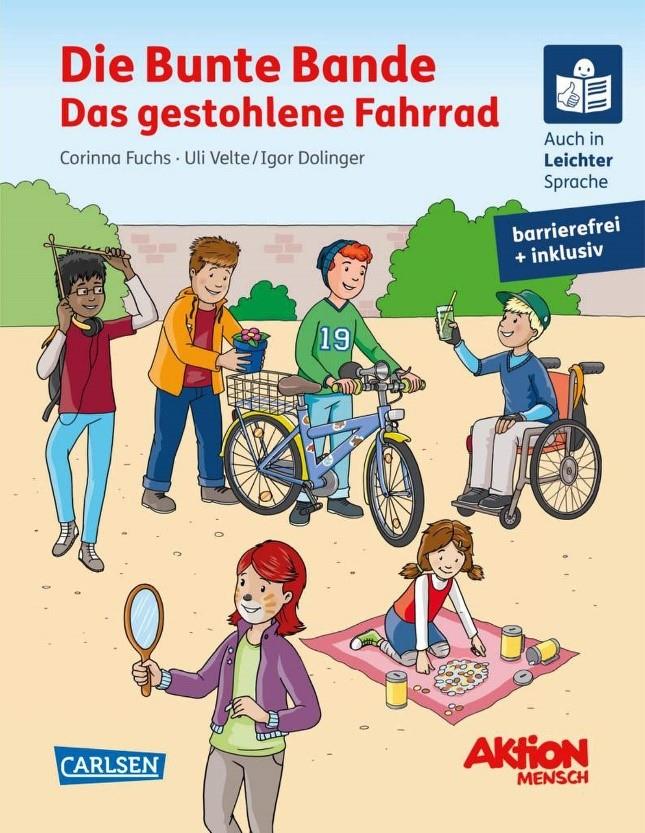

Fuchs, Corinna (text). Die Bunte Bande: Das Gestohlene Fahrrad. (The Variety Gang: The Stolen Bicycle). Hamburg, Germany: Carlsen Verlag GmbH, 2018. ISBN 978-3-551-06699-2. (2019 IBBY Catalogue)

Example 3

A mystery story written in everyday language and simplified easy-to-read text. It is printed in both large print font and Braille. Award winner from the 2019 International Association for Universal Design. One of the more accessible books in the IBBY Collection.

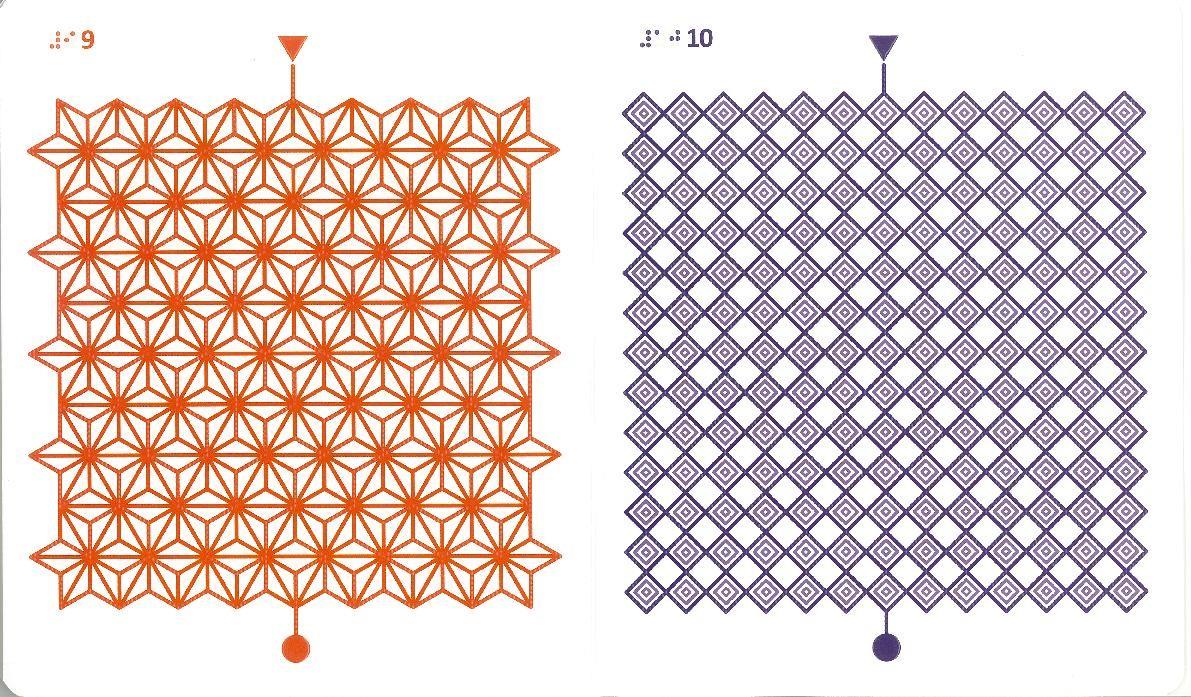

Murayama, Junko (design). Tenjitsukisawaruehon: Sawarumeiro (Touch Picture Book with Braille: Mazes by Touch). Tokyo: Shogakukan, Inc., 2013. ISBN 978-4-09-726497-2 (2015 IBBY Catalogue)

Example 4

Mazes designed with bumpy braille-like dots for fingers to discern pathways from top to bottom. Each of the 11 designs grows more complex and harder to navigate. The book is a pre-literacy tool for children who are learning to follow Braille but is also a fun activity for any reader.

Example 5

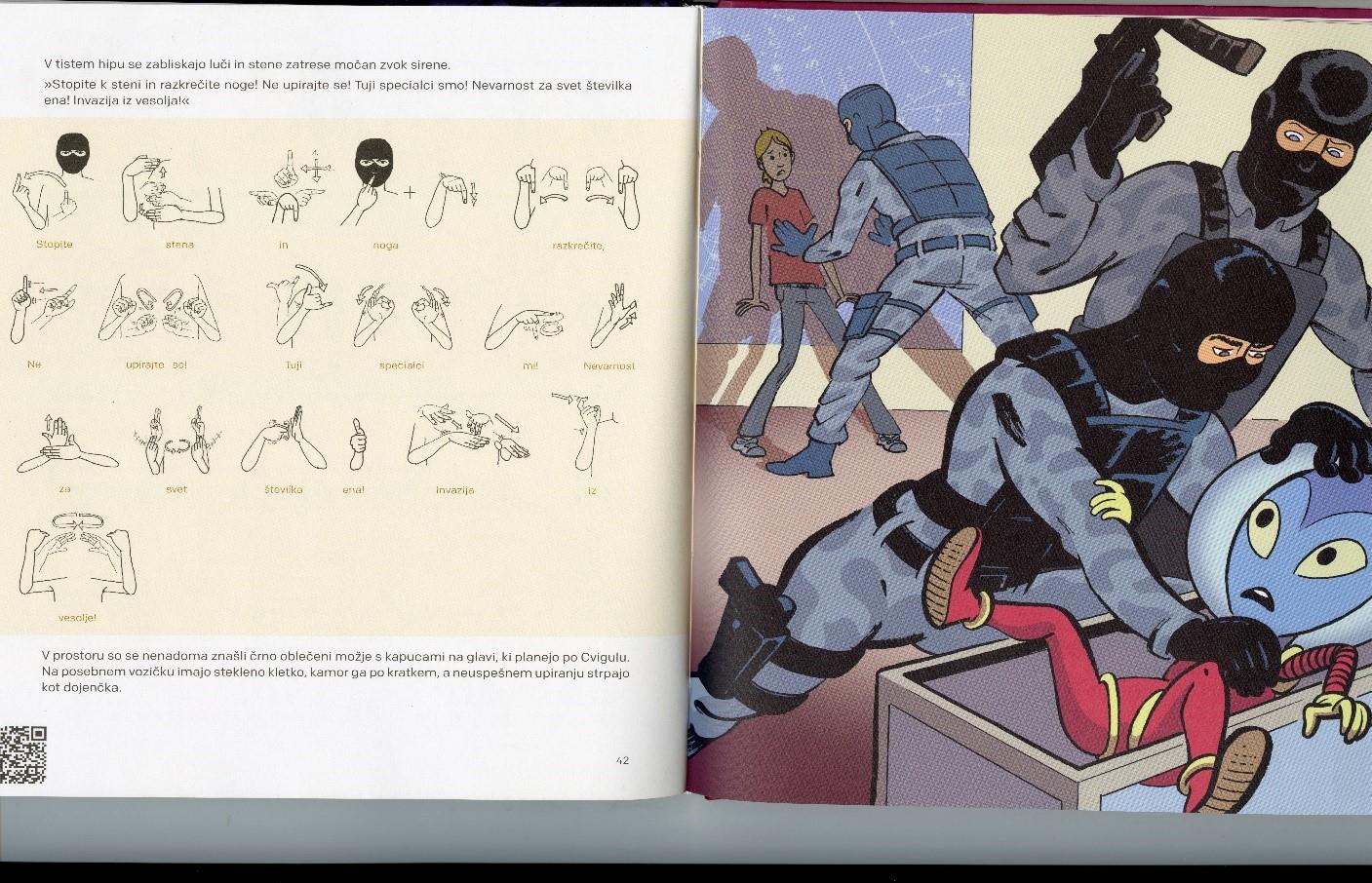

A science fiction book for older readers, in print and Slovenian Sign Language. Signed versions of conversations between the alien and main character are also available on videos accessed by QR codes. Special care was taken in the printed text to ensure that the sign language gestures included movement and facial expressions by an artist with lived experience.

Kermauner, Aksinja (text) Rus, Gašper (ill.), Vogel, Nikolaj (gestures), Ciglar, Veronika (sign language interpreter) David: MisijaMogoče (David: Mission Possible) Ljubljana, Slovenia: Zvezadruštevgluhih in naglušnihSlovenije, 2020. ISBN 978-961-94804-1-0 (2021 IBBY catalogue)

Example 6

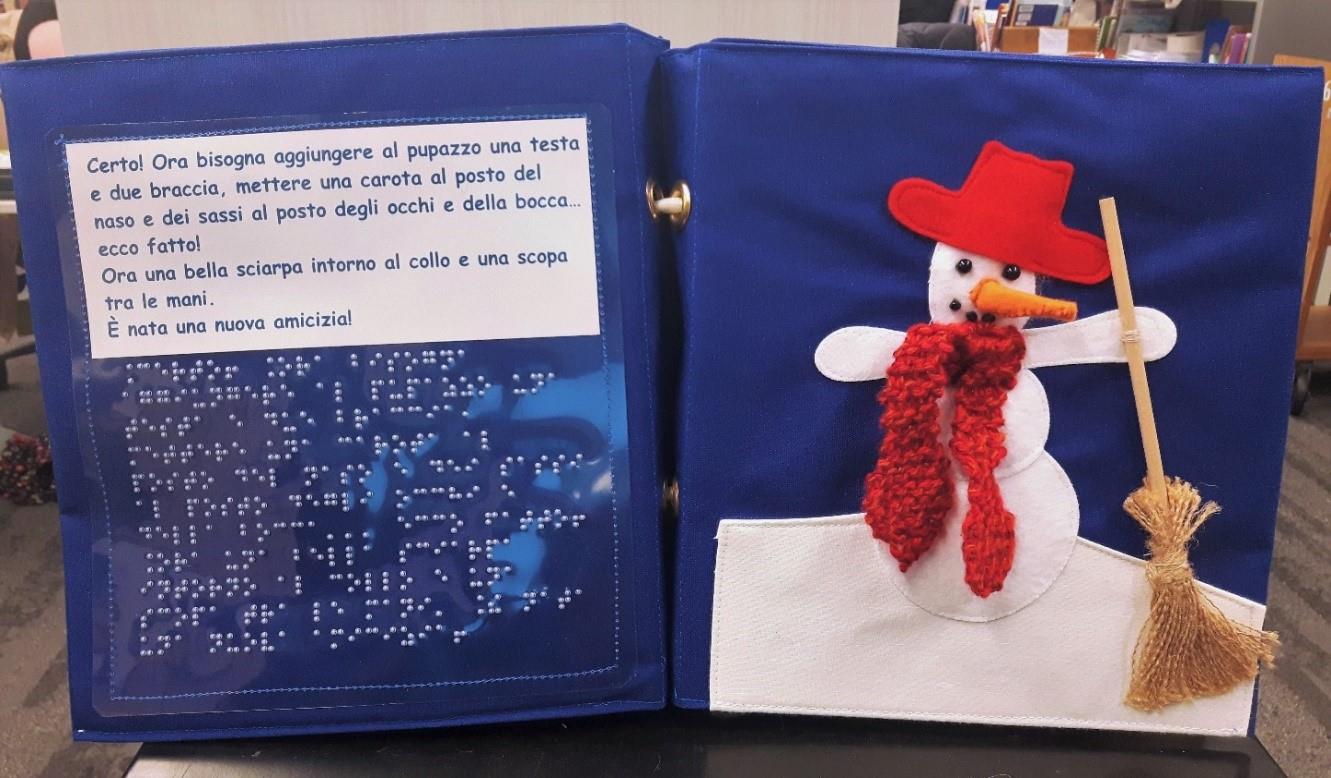

This amazing tactile book, fabricated by Les Doigts Qui Rêvent, and presented in bold large print and Braille, allows busy fingers to follow along page by page as a snowman is constructed. More than simply touching the pages, readers are also able to mimic the sound of a person crunching through the snow by pressing their fingertips into the snowbank on the first page. There is always more involvement and fun when the reader is able to employ more than one sense at a time.

Holstein, Irmeli and Katela, Minna. Un magicoinverno (A Magical Winter). Rome: ZajednoSocietàCooperativa, 2012. Original title: Talven Taika (Finlande, 2011) (2013 IBBY Catalogue)

Denise Scott is a disabled librarian at the Toronto Public Library. She is dedicated to learning and teaching others about how to make libraries more accessible for disabled people.

Leigh Turina is the lead librarian for the IBBY Collection for Young People with Disabilities as well as working as a children’s librarian. Two things that bring her great joy.