The Gatty Family – Close and Talented

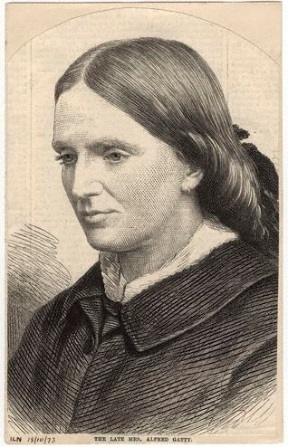

Margaret Gatty

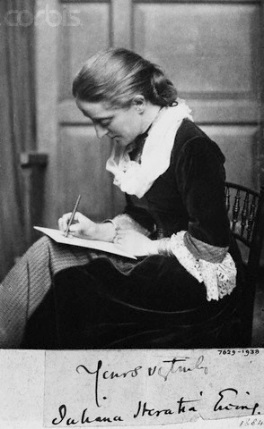

Juliana Horatia Gatty

Sarah Jardine-Willoughby

The Gatty family includes the nineteenth-century children’s authors Margaret Gatty, mother of the family, and her daughter Juliana Horatia Ewing, now largely forgotten, both were well respected. However other members of the family were talented too, as will be seen.

Margaret Gatty was the second daughter of Alexander Scott, a naval chaplain who served on The Victory with Nelson and has been described as Nelson’s spy. He was Nelson’s foreign secretary as he had a gift for languages and could gather intelligence. He sat with Nelson as he lay dying at Trafalgar, then accompanied Nelson’s body back to Britain. Scott married Mary Ryder, eloping with her in the face of parental opposition to their marriage. Their first daughter was named Horatia in memory of Nelson and a pledge made by Scott as Nelson lay dying, a tradition carried on in the following generations. Mary Scott died young when Horatia was three and Margaret was only two and they were brought up by their father and educated at home. He was a lifelong book collector and had a large library. Indeed when he was vicar of Catterick he left home with money to buy a pony but returned with books. The two girls were close, writing letters to each other in a code they developed when they were separated and forming the Black Bag Club; members wrote stories, poems or essays which were placed in the bag to be drawn out and read aloud. Margaret not only displayed literary talent, she also painted and did copper etching. However, many family responsibilities fell on her shoulders. Christabel Maxwell writes in her book Mrs Gatty and Mrs Ewing:

Upon Margaret fell most of the burdens, for her sister Horatia was beginning to show signs of the family eccentricity which led eventually to her departure from England in almost the Byronic manner, accompanied by a cat, a dog, and a guitar. (1949)

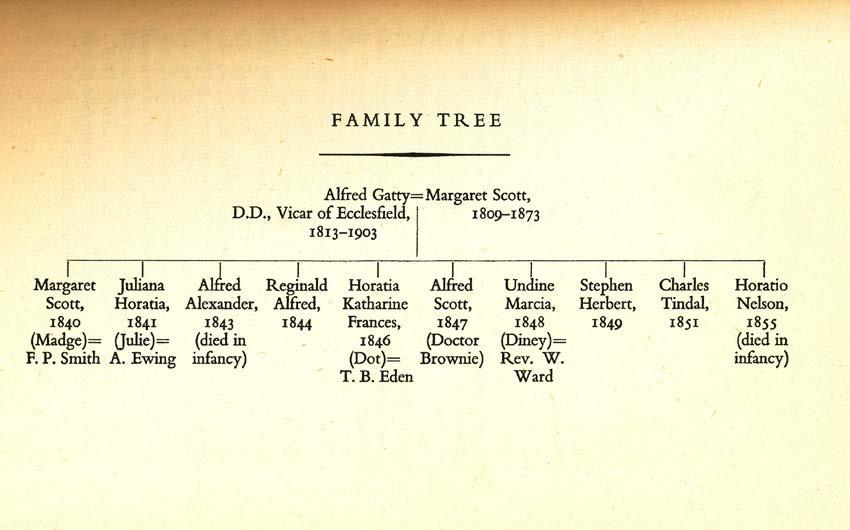

The Reverend Scott had become the vicar of Catterick, Yorkshire. Here Margaret met Alfred Gatty when he had a curacy on the Yorkshire moors and visited her father. Unfortunately Alexander Scott opposed their marriage at first, however it took place in 1839. While on their honeymoon Alfred was offered the living of Ecclesfield by an uncle of Margaret’s. Alfred Gatty was to stay there until his death in 1903. The Gattys were to have ten children, with two dying in infancy. Names are repeated, the family tree below shows this, family nicknames are also included in the family tree.

After the birth of Undine, her seventh child, Margaret went to convalesce in Hastings. It was here she developed her interest in seaweed after a suggestion from her doctor. This led to her becoming an expert in the subject, publishing a two-volume work in 1863, British Sea-Weeds. Drawn from Professor Harvey’s “Phycologia Britannica.” With Descriptions, an Amateur’s Synopsis, Rules for Laying Out Sea-Weeds. She even gives practical advice on how to dress for collecting seaweed. Juliana Gatty wrote a humorous poem about her mother’s obsession which was accompanied by a drawing that was included in the Gatty family magazine The Gunpowder Plot:

O Gatty’s! go and call your mother home

Call your mother home

At least in time for tea!

The breakfast, lunch and dinner come and go and come Unheeded, at the sea . . .

She passed this interest on to her daughter Horatia to whom she had bequeathed her collection. Margaret corresponded with marine biologists, and a couple of marine specimens were named after her. Her work has now been recognised and discussed in academic studies.

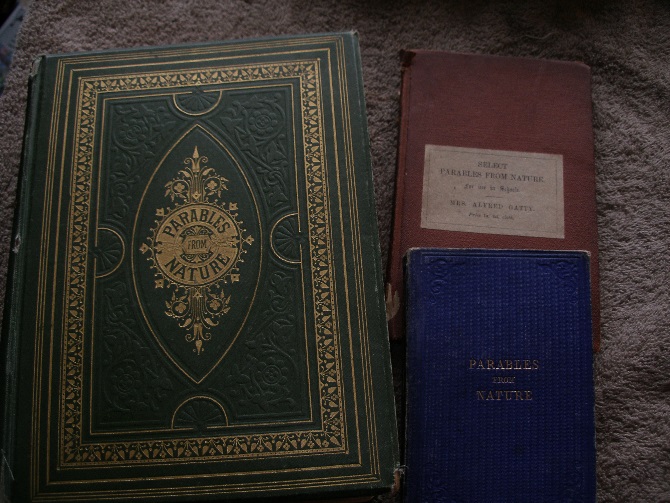

In fact, when Margaret published her first children’s book, The Fairy Godmother, in 1851 she asked for a marine-biology book as payment and another biology book as payment for the second edition. This book was followed by the first series of Parables from Nature in 1855. More series followed, a few of the parables appeared in The Monthly Packet of Evening Readings for Younger Members of the English Church, edited by Charlotte M. Yonge.

Various editions of Parables from Nature: The complete edition, Selections from Parables from Nature and an early edition.

A couple of her books appeared as Aunt Judy’s Tales and Aunt Judy’s Letters. Her last two books were published in 1872 – A Book of Sundials and A Book of Emblems, reflecting early interests; she had started to collect the mottos on sundials as a girl. Sadly she suffered a debilitating disease, now described as undiagnosed multiple sclerosis, making writing difficult. Thus, her daughters helped and acted as aides with this. Ultimately this caused her death in 1873.

Margaret and Alfred Gatty’s first child was Margaret Scott, born in 1840. She too painted, and illustrated her sister Juliana’s first book and provided illustrations for some of her mother’s Parables from Nature.

It was Juliana Horatia, the second child, who became known as the family storyteller; indeed one brother wrote to her from school asking for a story. She started her career as a published author with short stories in the Monthly Packet between July and December 1861, credited to J.H.G. They appeared in 1862 collected as Melchior’s Dream and Other Stories, edited by Mrs A. Gatty and illustrated by M.S.G. (Juliana’s elder sister, Margaret Scott Gatty) – a family collaboration.

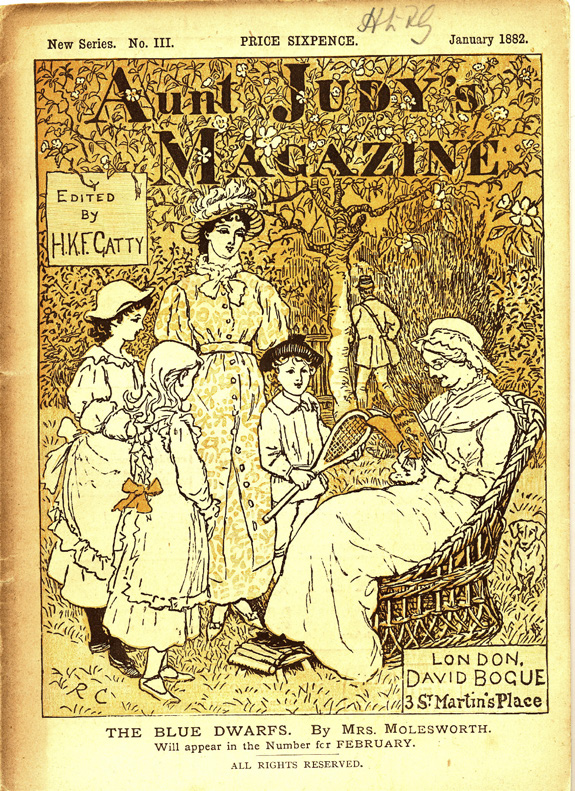

Cover illustration by Randolph Caldecott.

Juliana married Alexander Ewing, an army major, in June 1867 and within a week of marriage they were on their way to New Brunswick, Canada. She continued writing the serial she had started while in Canada and sent home her work for Aunt Judy’s magazine.

After returning to England ill health prevented her from accompanying her husband on future postings. However, she used the army background for some of her stories, notably for one of her very popular titles Jackanapes and also The Story of a Short Life. Jackanapes was originally illustrated by Randolph Caldecott, and included a coloured frontispiece (see above). Alexander Ewing returned to England in 1883 and they settled in Trull, Somerset. She established a garden there which inspired Mary’s Meadow.

Though known as an author, according to Christabel Maxwell, Juliana was proud of her painting too. She wrote short stories and longer ones which were serialised in Aunt Judy’s magazine, depicting families, indeed some of her descriptions of family life draw on her own experiences, Other stories have a fairy-tale theme – in ‘Timothy’s Shoes’ the wearer had to go to school or the shoes will pinch him. When Timothy does not go to church, the shoes go and so he is found out. Her story ‘The Brownies’ inspired the name taken up by the Girl Guides.

After her death in May 1885, her sister Horatia wrote a biography Juliana Horatia Ewing and her Books, which includes a detailed bibliography of her work. This was included as the eighteenth volume when her complete works were published in 17 volumes (including her writing for adults).

Juliana was well regarded during her lifetime. Mrs Molesworth wrote an article ‘Mrs Ewing’s Less Well-Known Works’ published in the Contemporary Review in March 1886, and her stories were in print in the early part of the twentieth century. Since then two of her stories have been retold by Berlie Doherty and issued as picture books.

A collection of her letters was published in 1983, Canada Home: Juliana Horatia Ewing’s Fredericton Letters 1867–1869, and Illustrated News: Juliana Horatia Ewing’s Canadian Pictures, 1867–1869 was published in 1987.

It was a large close family.

Younger brother Reginald Alfred studied law before becoming a clergyman like his father. He was appointed vicar at Bradfield. He seems to have suffered concerns about his vocation in 1870 and travelled to Belgium, and closer to the front line of the Franco-Prussian war. He became a temporary member of the Red Cross before he returned to Bradfield. He died in 1914.

Her sister Horatia, always known as Dot, worked closely with their mother both with the sorting and the collecting of seaweed. She also helped her with her work on Aunt Judy’s magazine as Margaret became less able to write, and also with Margaret Gatty’s last two books. After Margaret Gatty’s death she moved to London to be nearer the publishers and became a publisher’s reader too.

Alfred Scott Gatty was born in 1847 and later changed his name to Scott-Gatty in 1892. He was described as a composer in the 1871 census. Though a member of the College of Arms – indeed in 1904 he became Garter King of Arms and played a leading role in organising various state ceremonies, including the funeral of Edward VII and the coronation of George V – he continued composing and contributed music to Aunt Judy’s magazine regularly. He was knighted in 1904.

Juliana’s youngest sister Undine Marcia (photo by Juliana) was described as her father’s unpaid curate. Her sister Juliana wrote in a letter to her husband about Undine ‘consuming life in the treadmill of running errands for the Governor and slaving at the parish’. Undine married the Reverend Walter Ward, her father’s curate in 1884, A story was passed down the family that Alfred Gatty tried to persuade his daughter not to marry and said he would give up his second marriage if she would give up her marriage. Her daughter Christabel Maxwell was the author of Mrs Gatty and Mrs Ewing.

Then there were the two youngest surviving brothers. Stephen Herbert studied at Oxford and became a barrister in 1874 and a QC in 1891. He became a colonial law officer serving in various places, including the Caribbean, before becoming Chief Justice of Gibraltar (1895–1905). He was knighted in 1904. His daughter Hester married Siegfried Sassoon. Stephen was musical, a watercolour painter and an amateur actor contributing to the family theatricals. The youngest was Charles Tindall born in 1851. He seems to have failed to get into university and undertook parochial work in the East End of London: Juliana thought he would make a good clergyman. In the end he became curator of the Liverpool Museum before a variety of different jobs. He was the unsuccessful Irish Home Rule candidate for West Dorset in 1892. He was well travelled and also a published writer. He wrote a two-volume history of the Grosvenor family and its estates, Mary Davies and the Manor of Ebury. He died in 1928.

In 1866 Margaret Gatty edited Aunt Judy’s magazine, a new monthly magazine for children published by George Bell. Two sources write that Margaret Gatty was asked by George Bell to edit it and Susan Drain writes that Alfred Gatty suggested the idea to the publisher.

Aunt Judy’s magazine was issued monthly, featuring articles, stories and reviews. The first book reviews section was in the second issue, June 1866; the first review was of Alice in Wonderland. The magazine was collected into two volumes, the Christmas volume and the May Day volume for the first few years until it became an annual publication. Aunt Judy’s magazine was truly a family enterprise as many members of the Gatty family contributed to it. The first volume – the Christmas volume for 1866 – as well as articles on natural history by the editor, has an article by Alfred Gatty on ‘Sea Forts at Spithead’, the first instalment of Juliana’s story ‘Mrs Overtheway’s Remembrances’, which continued for several years. Alexander Ewing contributed music and ‘The Prince of Sleona’, a serial, also several pieces of music by Alfred, who continued to contribute to future issues, composing music for some of the songs in Alice – ‘The Walrus and The Carpenter’, ‘Pig and Pepper’ and ‘Will You Won’t You Join the Dance’.

Other members of the family contributed regularly too. Reginald, under the pseudonym LLB, contributed stories from his childhood and some poems, including two both titled ‘To J.H.E’ and written for his sister when she was in Canada. He also contributed illustrations, as did Alfred. Stephen contributed plays, using his initials SHG. Charles contributed articles about some of his travels. Margaret Gatty’s sister Horatia, under her initials HSE, also wrote for Aunt Judy – and there was even a poem by the Reverend Walter Ward.

Aunt Judy’s magazine was edited by Margaret Gatty until she died. After her death Juliana and her sister Horatia became joint editors. Then Horatia became sole editor – indeed, she had always helped her mother in this role. The magazine was one of the most popular of its time – through its readers, more than one cot in Great Ormond Street Hospital was sponsored and were regularly featured. Susan Drain writes:

Aunt Judy’s Magazine was an amateur effort and a family affair, particularly for the first seven and a half years . . .. By amateur, I mean the editorial, though not the publishing, work was done by people whose identity was not primarily that of the professional writer or editor, and whose livelihood did not depend on that work alone. (2007)

I don’t agree totally with this statement as Margaret Gatty started writing to augment the family income, especially needed with a large family. She was able to attract well-known writers, including Lewis Carroll, featuring ‘Bruno’s Revenge’ which later became part of Sylvie and Bruno. There were stories by Hans Christian Andersen too and one by Mrs Molesworth.

Sadly Aunt Judy’s magazine ceased publication in 1885 (it was not a profitable venture) with a farewell note from Horatia Gatty citing the death of Juliana Ewing as the reason and that she could not be replaced as her contributions were so integral to Aunt Judy‘s. Also the name would be meaningless as she was ‘Aunt Judy’. The last volume includes a song ‘To J.H.E.’ with words and music by Alfred and a serialised memoir of Juliana by her sister Horatia.

It is interesting to note that the first biographical writings about both Margaret Gatty and Juliana Horatia Ewing were by family – Juliana on Margaret, Horatia on her sister and Christabel Maxwell on them both.

I think the fact that most of the family contributed to Aunt Judy’s illustrates what a close family they were, even if they were physically apart. Also, I wonder if Margaret Gatty had had a more conventional upbringing and more of an interest in domestic matters and had just devoted all her time to supporting her husband’s parish, would her children have achieved as much?

Works cited

Aunt Judy’s magazine – various annual volumes are available online at https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/008699163.

Bryant, J.A. et al. (2016) Life and Work of Margaret Gatty (1809–1873), with Particular Reference to British sea-weeds (1863). Archives of Natural History 43.1: 131–147.

Cosslett, T. (2003) ‘Animals under Man’? Margaret Gatty’s Parables from Nature. Women’s Writing 10.1.

Doherty, Berlie and Robin Bell Corfield (1996) Our Field [based on a story by Juliana Horatia Ewing]. London: Collins.

Drain, Susan (2007) Family Matters: Margaret Gatty and Aunt Judy’s Magazine. Publishing History 61: 5–45.

Ewing, J.H. (1873) In Memoriam: Margaret Gatty. Aunt Judy’s Magazine November 1873.

Ewing, J.H. (1882) Memoir of Margaret Gatty. In Parables from Nature. New and Complete edition. London: George Bell and Sons.

Gatty, Mrs Alfred (1872) British Sea-Weeds. Drawn from Professor Harvey’s “Phycologia britannica”. With Descriptions, an Amateur’s Synopsis, Rules for Laying out Sea-Weeds, an Order for Arranging them in the Herbarium, and an Appendix of New Species. London: Bell and Daldy.

Volume 1:

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015061870534&view=1up&seq=7

Volume 11:

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015061870526&view=1up&seq=7

Gatty, Horatia K.F. (1885) Juliana H Ewing and her Books. London: SPCK. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/17085/17085-h/17085-h.htm. [Memoir first serialised in Aunt Judy’s magazine 1885 without the details of Mrs Ewing’s publications.]

Jones, Joan and Mel (2003) The Remarkable Gatty Family of Ecclesfield. London: Green Tree Publishing.

Maxwell, Christabel (1949) Mrs Gatty and Mrs Ewing. London: Constable.

Sheffield, Suzanne Le-May (2013) Revealing New Worlds: Three Victorian Women Naturalists. Abingdon: Routledge. [Limited preview at

https://books.google.co.uk/books/about/Revealing_New_Worlds.html?id=mg-humJ9KzIC&redir_esc=y.]

Sumpter, Caroline (2008) The Victorian Press and the Fairy Tale. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Knoepflmacher, U.C. (1908) Repairing Female Authority: Ewing’s ‘Amelia and the Dwarfs’. In Ventures into Childhood: Victorians, Fairy Tales, and Femininity Chapter 11: 378–424. Chicago IL: University of Chicago Press.

Molesworth, Mary Louisa(1886) Juliana Horatia Ewing. Contemporary Review 49, May 1886: 675–686. Reprinted in A Peculiar Gift: Nineteenth Century Writings on Books for Children. Selected and introduced by Lance Salway. Harmondsworth: Kestrel Books, 1976.

Website

Reverend Dr Alfed Gatty. A page from St Mary’s Parish Church, Ecclesfield. https://www.stmarysecclesfield.com/History/Revd_Dr_A_Gatty.html.

Susan Bailes taught for 36 years and retired from a Surrey headship in August 2012. She was one of the early MA in Children’s Literature cohorts at Roehampton University and continues to carry out research. She values serving on the committees of IBBY UK and the Imaginative Book Illustration Society, is Chair of the Children’s Books History Society and regularly reviews books for these organisations. She has a particular interest in doll literature and all it reveals about the historical context in which it appears. One of her talks ‘Kathleen Ainslie (1858–1936): A Forgotten Female Edwardian Illustrator of Children’s Books’ was published in Studies in Illustration, no. 66, Summer 2017 and another was on ‘Fashioning Dolls: Different Treatments and Attitudes Revealed in Children’s Texts’ published in IBBYLink Spring 2019 entitled ‘Hobbies and Crafts in Children’s Books’, the theme of the 25th IBBY UK/NCRCL MA conference.