Storytime and Engaged Learning with an Informational Poetry Picture Book

Karen Bentall

Non-fiction picture books are a staple of storytime for me and my 620 students.

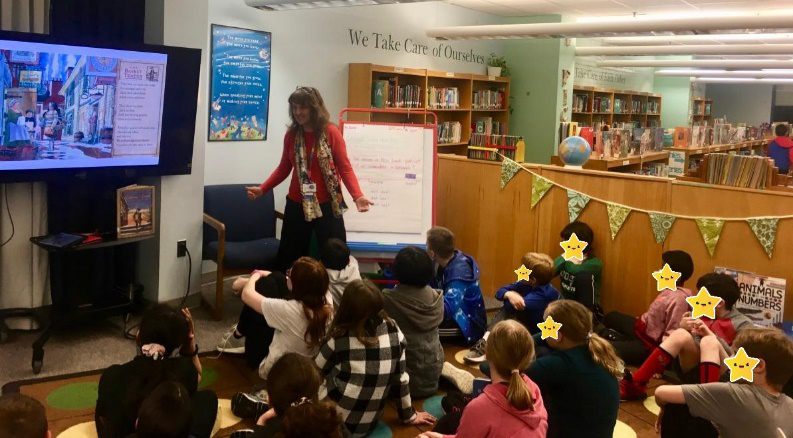

I work at a school where almost 25% of students are economically disadvantaged. More than 30% are learning English as a second language. Yet I sense that they all, regardless of background knowledge or ability, enjoy listening and responding to non-fiction picture books. Scaffolded discussions develop their skills for visual and literacy interpretation, and the type of critical thinking that they will need for their own good and the good of others in a complex, confusing, changing world. But like classroom teachers, I am required to provide evidence of learning. I tried various assessment techniques, but none captured the sense of enchantment and intellectual growth that occurred during storytime discussions. It was palpable and powerful, but I couldn’t explain how or why. Because it couldn’t be explained, it couldn’t be measured. And because it couldn’t be measured, it wasn’t valued in the data-driven education climate in which I work. In an attempt to understand, I took a year’s study leave at the University of Cambridge to pursue an MPhil in Education with a focus on critical approaches to children’s literature. My 20,000-word thesis detailed empirical research with 142 fourth-grade (age 9–10) students who were learning about the complex, confusing and changing world of the period leading up to the American Revolution. (Dare I call it Brexit 1773 style? The people were divided, and tempers were high.) Seven highly qualified and experienced classroom teachers with contextual knowledge about their students observed the storytime lessons. They completed surveys during and after the lessons, which provided the data for my study.

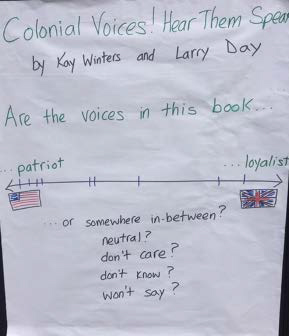

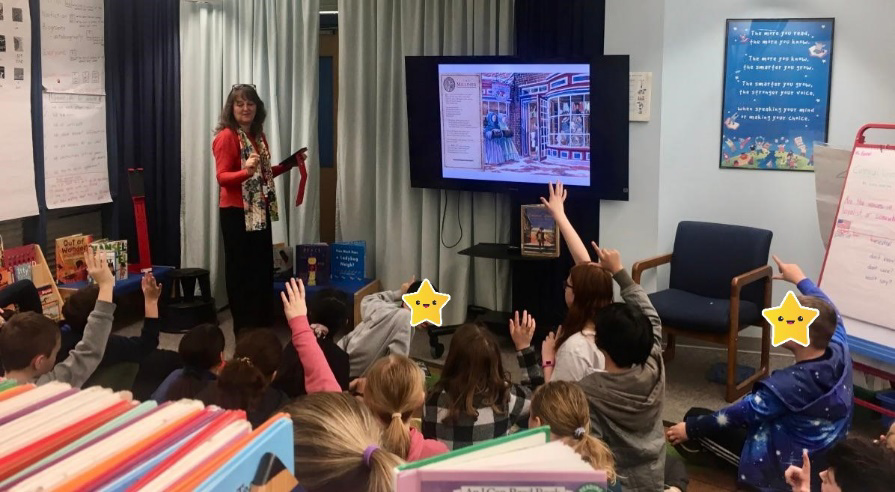

I used an electronic version of the book displayed on a large screen. As students stepped up to the screen to point to the part of the text that supported their reasoning, I could instantly magnify the words allowing the entire class to visually focus on the evidence while listening. To begin, I asked the students to look at the front cover and a poster I had prepared in advance.

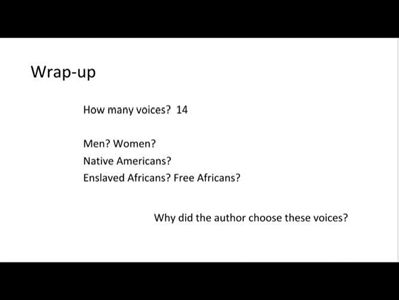

The enslaved man is hunched toward the fire and bound by chains. Their postures alone suggest the power dynamic between master and slave. Ethan stands between them, suggesting that there is only one voice that matters in this room. This image is characteristic of the way that slavery has been taught in the past. It is one-dimensional. It denies the myriad covert and overt ways that enslaved people resisted. Colonial Voices tends to deflect, rather than invite, critical engagement here because it gives only one perspective for the enslaved. This ideological stance is especially problematic in Virginia where the legacy of the arrival of the first documented Africans 400 years ago can be seen and felt today. Most notable are the events of Charlottesville in August 2017 where counter-protester Heather Heyer was killed during a white-nationalist rally. Lawrence Sipe, in his book Storytime: Young Children’s Literary Understanding in the Classroom (2008), asks how children might learn to identify ideologies through literary understanding (p.238), because doing so helps them to think critically about how stereotypical racial, sexual and class attitudes are implicitly inscribed and how they shape social norms today. After leading a discussion about the perspective of each colonist, I asked students to consider these questions:

In his book A Literature of Questions: Nonfiction for the Critical Child (2018), Joe Sutliff Sanders explores the vulnerability of characters. When non-fiction reveals characters’ mistakes and flaws, it encourages rather than negates children’s critical thinking. It is evident in the verse that describes the act of throwing the tea crates off the ships into the harbour: the Boston Tea Party. ‘On British warships docked nearby/ no sailor sounds a warning’ followed by blank space that demands a pause. Were the sailors sleeping? Was no one on the warship on lookout duty? Is this a glimpse of a crack in authority? Was the British navy complacent? Or did the sailors notice the ‘Mohawks’ but refrained from leaping to the defence of the tea company? In addition to the multiple perspectives of the colonists, here readers might consider that not every British subject was a staunch supporter of King George III and parliament.

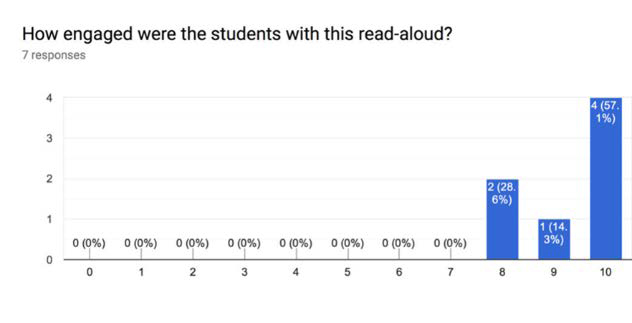

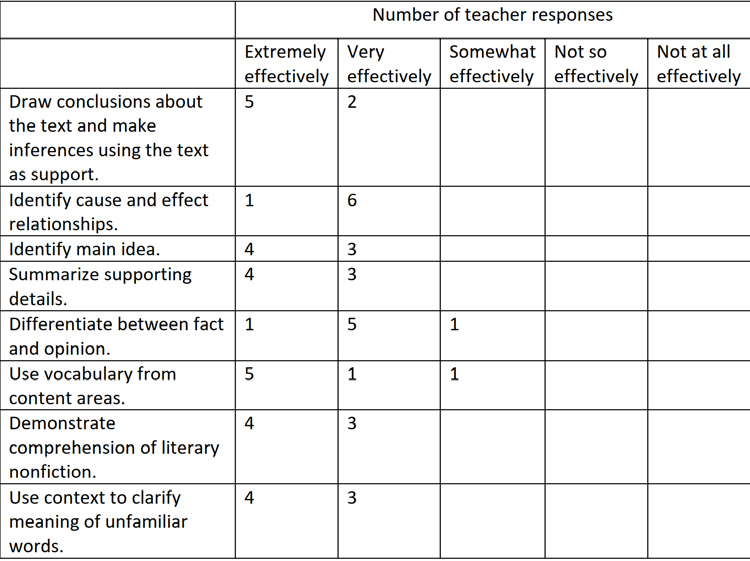

How effective was this lesson? Were all 142 students critically engaged with the content? Seven teachers with contextual insight and knowledge about their students observed the lessons.

Also, I tried to make this study about the book and not about me, but I found that my performance of the text couldn’t be separated and isolated. The orality of the poetry and my use of accents breathed life into the characters. Teachers perceived this to be a factor in sustaining engagement during this hour-long lesson. So perhaps this lesson is not easily replicated by teachers who feel less confident with the performative aspect of storytime. My background in reading aloud stems from my childhood in Wales, where I was steeped in the rich oral tradition of the Welsh language and poetry recitation at Eisteddfods. Teresa Cremin (2009) of the University of Cambridge led one study that revealed the crucial role that teachers’ personal passion for poetry plays in the motivation of reluctant readers. If reading poetry aloud – and especially poetry combined with non-fiction – is a proven instructional strategy that motivates and engages every student in the seamless integration of literacy and curricula objectives, then more room should be made for it in the professional development of teachers and librarians.

Since this small study, I have returned to my school with new insight and a renewed conviction about the power of storytime and dialogue, but I’m still searching for more ways to provide evidence of the effect they can have on children’s wellbeing and intellectual development. Recent research reveals inequality of access and opportunity to school libraries. There is a stubborn education attainment gap in England and the US that persists despite years of interventions. Too many children are still being left behind. In a future that seems likely to include increasing inequality, political instability and climate change, children need to develop critical thinking skills and empathetic dispositions to navigate a path for their own good and for the good of others. Non-fiction books, especially those that invite dialogue through a transparent research process, and engage readers with poetic text and captivating illustrations, can be powerful tools to cultivate the promise of every child.

Works cited

Primary work

Winters, Kay (illus. Larry Day) (2008) Colonial Voices! Hear Them Speak! New York: Puffin.

Secondary works

Cremin, Teresa, et al. (2009). Teachers as Readers: Building Communities of Readers. Literacy 43(1), pp.11–19.

Great School Libraries. National Survey Results. https://www.greatschoollibraries.org.uk/news.

Sanders, Joe Sutliff (2018) A Literature of Questions: Nonfiction for the Critical Child. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Sipe, Lawrence R. (2008) Storytime: Young Person’s Literary Understanding in the Classroom (Language & Literacy). New York: Teachers College Press.

Winters, Kay (illus. Larry Day) (2018) Voices from the Underground Railroad. New York: Dial.