Stories in Detail: Wimmelbooks and Narrative

Elys Dolan

When writing and illustrating picture books I’ve always found the devil is in the detail.

I can’t help but surround the central narrative with extra characters, detailed settings and subplots to create intricate worlds. To do this I naturally gravitated towards creating highly detailed imagery. This wouldn’t surprise anyone who knew how I’d spent my early years obsessing over Martin Handford’s Where’s Wally? and Richard Scarry books.

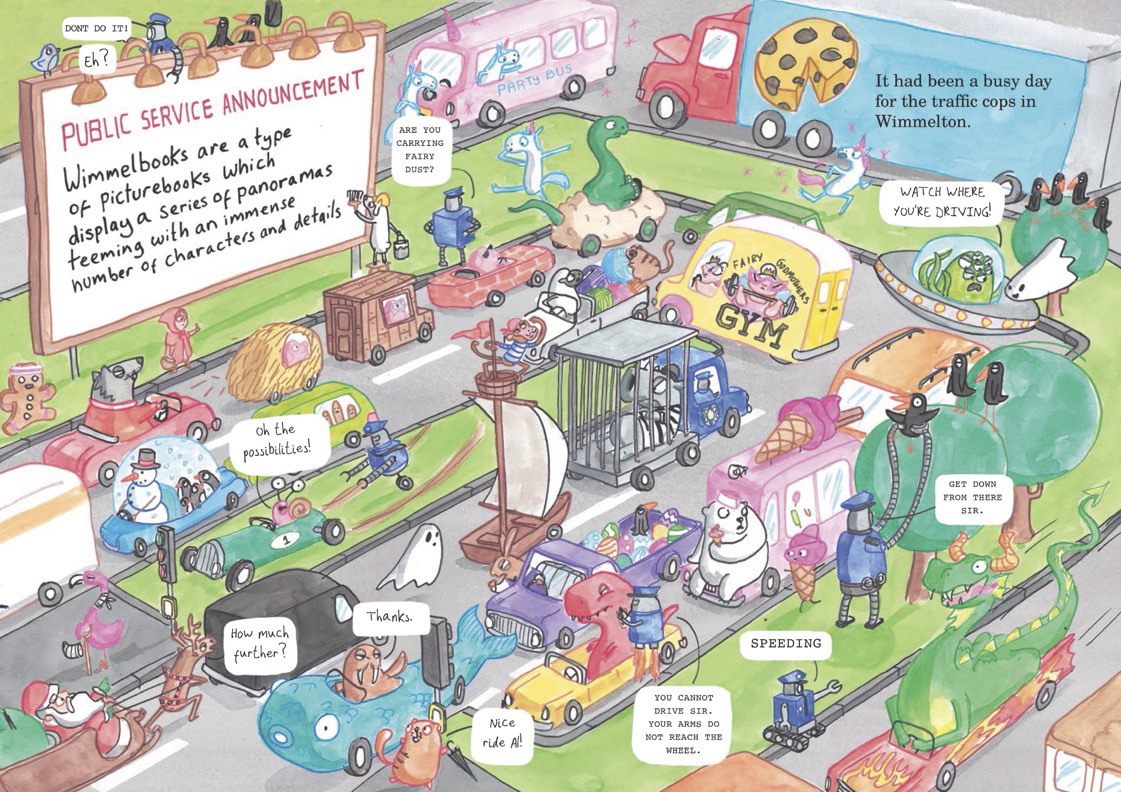

Later, as a fully fledged adult doing a PhD in picture books and still obsessing over Where’s Wally? (one day I will find him!), I discovered these detailed books have a name, wimmelbooks. Although not much has been much written on the subject of wimmelbooks we are fortunate to have one main researcher, Cornelia Rémi (2011), who has explored the subject. She defines wimmelbooks as ‘a type of wordless picture book which displays a series of panoramas teeming with an immense number of characters and details’. This is a definition I’d broadly agree with but I’d suggest a slight amendment. In the course of my research I’ve found that when talking about visual concepts sometimes it’s more effective to show rather than describe so I’ve created a visual definition to show you what I believe a wimmel image is.

Here I’ve removed ‘wordless’ from the definition so it reads, ‘Wimmelbooks are a type of picture book which displays a series of panoramas teeming with an immense number of characters and details’. Rémi’s definition fits neatly around the German tradition of wimmelbooks, including the brilliant work of Rotraut Susanne Berner, where these detailed books are often wordless, but this change allows for what Nikolajeva and Scott (2001) describe as ‘the unique characteristic of picture books as an art form’, the combination of two levels of communication, the visual and the verbal. It expands the scope and versatility of wimmelbooks and, more importantly, it encompasses a shared factor that unites many such detailed books and describes my own motivation to use wimmel imagery. That factor is the ‘wimmel’ itself. Let me elaborate.

The word ‘wimmelbook’ comes from the German word ‘wimmelbuch’ (Cuperman, 2014). The Collins German Dictionary (2005) says ‘Wimmeln’ translates as ‘to teem’ and ‘buch’ as ‘book’. It is this teeming nature, the ‘immense amount of characters and details’ (Rémi, 2011), that I believe is the key feature of these books.

Having a huge number of characters doing a variety of things in an expansive and detailed setting can convey a substantial range of information to the reader on a single page. Much more so than through the imagery traditionally associated with picture books. Through this high level of detail a wimmelbook can offer depth of understanding of a fictional world and so the characters and the narratives occurring within it. It’s this effect that makes using wimmel imagery a unique way of working. I’m going to refer to imagery that involves this teeming detail and exhibits the effects described above as having wimmelbook characteristics.

Now onto the bit I really enjoy, what you can do with these wimmelbook characteristics.

For instance, you can add purpose to the reader’s exploration of the detail by giving them an objective, creating a game or puzzle. This is seen in Where’s Wally by Martin Handford (1987) and Pablo and Jane by José Domingo (2015). Alternatively, being able to show in detail how complex structures interconnect using wimmel images can be incredibly useful for non-fiction. This is seen in What Do People Do All Day? by Richard Scarry (1968) and Castle Cross-Section by Stephen Biesty (1996).

The thing I want to demonstrate in more depth though is how wimmelbook characteristics can be used in visual storytelling. I believe their greatest strength within a narrative picture book is their utility in creating intricate, immersive and fully formed worlds. To demonstrate this we need to take a trip to a strange and foreign land ….

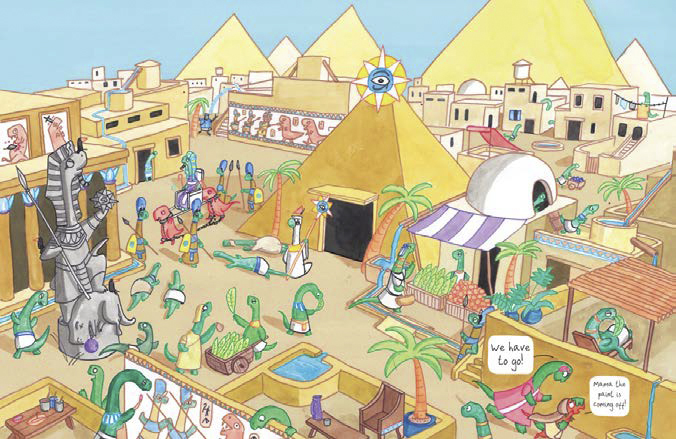

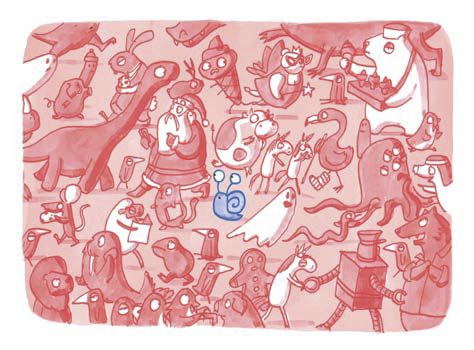

Explore the details of the particular world to the below. Pay close attention, there will be a quiz later.

From looking at the wimmel image above can you tell me …

- Who or what lives in this city?

- Who or what lives in this city?

- What are their houses like?

- What do they eat?

- What do they worship?

- Who’s in charge?

- Are there any conflicts?

- Do they play any games?

If you can answer at least some of those questions then this demonstrates how you can use wimmel imagery to create an expansive and fully formed setting in a single image. This is also seen in Marc Boutavant’s Around the World with Mouk (2009) where he uses wimmel images of particular countries to convey a wide range of details and facts about that place. Cléa Dieudonné’s Megalopolis (2016) uses one huge wimmel image to depict the workings of an entire city and an alien’s journey through it.

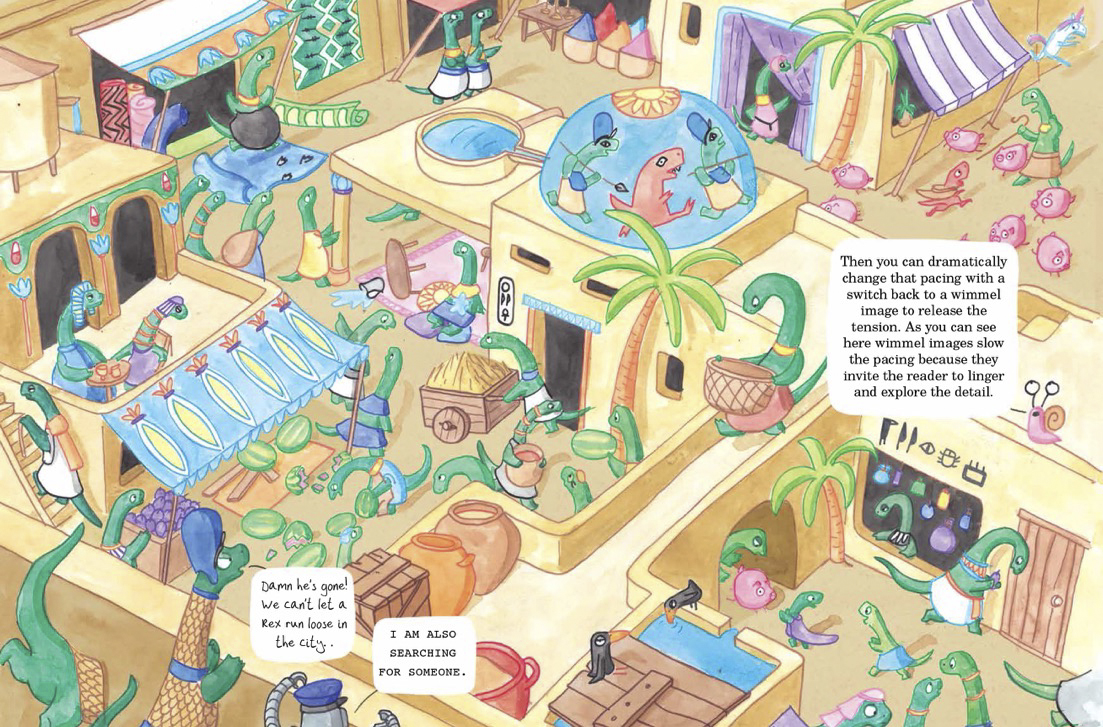

For me such a detailed setting begs to have a story woven around it because it makes the narrative more immersive and convincing whilst adding depth and understanding to the characters and situations. Nikolajeva and Scott (2010) say the setting can ‘convey narrative time, for instance, by a change of seasons, enhance characterisation, suggest a mood, or add detail not mentioned in the text’. In this particular case I’ve used the setting to set up the mood and characterisation for these characters.

Did you notice them?

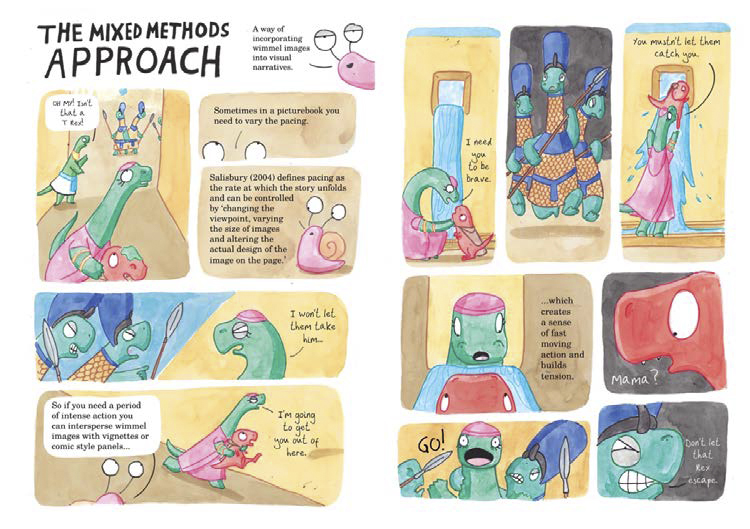

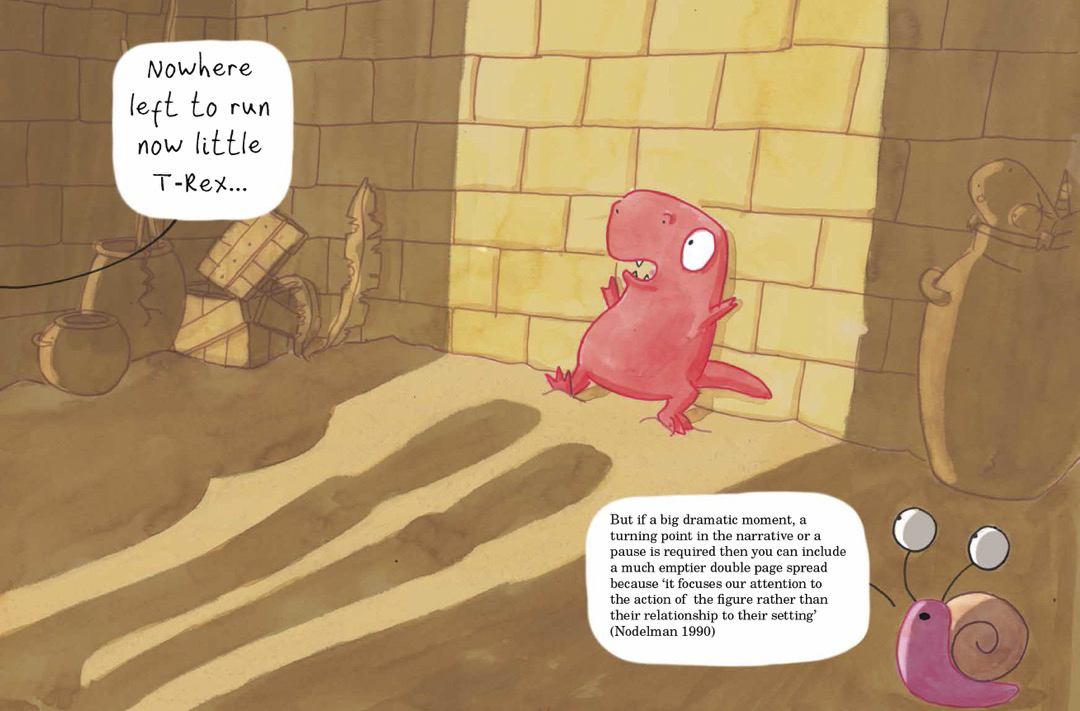

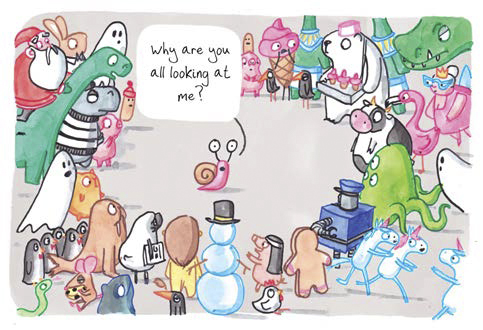

I placed them in the bottom right-hand corner of the previous image to draw attention to them and trigger the narrative. To tell their story using just wimmel images though could be limiting. In the images below my colleague Snail will talk through a way of managing this.

So if you intermingle wimmel images with other methods of visual storytelling they can enhance a narrative whilst not losing the storytelling ability of the wimmel images. That’s not to say you have to do this. In The Bear’s Song (2013), Benjamin Chaud artfully conveys a linear narrative, exclusively using wimmel images.

Another advantage of wimmel imagery is that it allows the maker to include subplots and asides that exist independently of any central narrative amongst the detail. The reader can then spot these as they follow the story. I can’t demonstrate one of these subplots visually in this context, but you can find a great example in Matty Long’s Super Happy Magic Forest (2015). Here the reader can follow the alternate adventure of Dennis the butterfly alongside the central narrative.

One of the advantages of subplots is that they enhance repeat readings. The reader can revisit the story and find something new that either adds to the central narrative or augments the world in which it’s set.

The biggest challenge of using wimmel images narratively is arguably composition. It can be difficult to distinguish particular elements and lead the reader across the image in a specific manner. There are visual ways around this though.

Scale: Increase the volume of space taken up by the focal object to draw attention to it through the teeming detail.

Colour: Make the focal object a contrasting colour to distinguish it.

Space: Using the way in which the detail is composed to create negative space around the object.

In this article I’ve endeavoured to show ways in which a maker can utilise wimmel images to tell a story with a central narrative. It is the detailed, teeming nature of the wimmel images that allows them to convey a large amount of information and so enhance setting, mood and characterisation, whilst allowing additional subplots and inviting repeat readings. Wimmel imagery is being used by a wide range of picture-book makers to great effect for purposes ranging from narrative to non-fiction and puzzle books, so demonstrating its versatility.

On a personal level I can’t help but keep trying to improve the way I use wimmel imagery to create richer stories. From my first picture book Weasels, which depicts the secret base teeming with villainous weasels bent on world domination, to my latest offering Mr Bunny’s Chocolate Factory, which shows the intricate workings of the Easter Bunny’s chocolate-egg factory, I’m doing my best to harness teeming detail to give my readers new and fascinating worlds to explore.

[This article has been adapted from Elys Dolan’s pictorial essay ‘How Wimmelbooks Work: A Snail’s Guide’.]

Reference works cited

Rémi, Cornelia (2011) Reading as Playing: The Cognitive Challenge of the Wimmelbook. In Bettina Kümmerling-Meibauer (ed.) Emergent Literacy: Children’s Books from 0 to 3. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp.115–140.

Nikolajeva, Maria and Scott, Carol (2001) How Picturebooks Work. Abingdon: Routledge.

Nodelman, Perry (1990) Words about Pictures. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press.

Salisbury, Martin (2004) Illustrating Children’s Books: Creating Pictures for Publication. London: A & C Black.

Salisbury, Martin and Styles, Morag (2012) Children’s Picturebooks: The Art of Visual Storytelling. London: Laurence King.

Terrell, Peter (2005) Collins German Dictionary. London: Collins.

Children’s books cited

Biesty, Stephen and Platt, Richard (1994) Stephen Biesty’s Cross-Sections: Castle. London: Dorling Kindersley.

Berner, Rotraut Susanne (2008) In the Town all Year Round. San Francisco, CA: Chronicle Books.

Boutavant, Marc (2009) Around the World with Mouk. London: Tate Publishing.

Dieudonné, Cléa (2016) Megalopolis: And the Visitor from Outer Space. London: Thames and Hudson.

Chaud, Benjamin (2013) The Bear’s Song. San Francisco, CA: Chronicle Books.

Domingo, José (2015) Pablo & Jane and the Hot Air Contraption. London: Flying Eye Books.

Handford, Martin (1987) Where’s Wally? London: Walker Books.

Long, Matty (2015) Super Happy Magic Forest. Oxford University Press.

Scarry, Richard (1968) What Do People Do All Day? New York: Random House Books for Young Readers.

Elys Dolan is an author and illustrator living and working in Cambridge, UK. Her recent books include Steven Seagull Action Hero, The Doughnut of Doom and the forthcoming Mr Bunny’s Chocolate Factory. Along with this she is studying for her PhD in humour in picture books at the Cambridge School of Art and lectures on the MA in Children’s Book Illustration there. In her spare time Elys enjoys growing cacti, making fudge and having a quiet lie down.