On Writing Lydia, The Wild Girl of Pride and Prejudice

It was not my idea to write Lydia. The project came about as a result of a random conversation with a friend about Jo Baker’s marvellous Longbourn (2014), who mentioned it to her publishing colleagues at Chicken House, who had had some success with previous retellings of classics and thought Lydia’s story might be rather saleable.

Imagine my surprise, then, at what came next.

I signed the contract, and panic swept aside my cavalier assurance. Jane Austen! What was I thinking? I knew almost nothing about her. I had never studied her – I knew the TV adaptations better than the novels. And the world, I quickly discovered, was full not only of Austen scholars, but also of Austen super–fans, prepared (I was quite certain) to cross continents in period costume to pierce me with a darning needle if I got the slightest detail wrong …. I had been rash and impetuous.

I had behaved, in short, rather like Lydia herself.

Well, the contract was signed, and it was too late for hand wringing. My only option was to learn as much as possible in the little time I had (and did I mention the ridiculously short production schedule I had airily agreed to?). I threw myself into research with all the enthusiasm and determination of the youngest Miss Bennet in pursuit of a regimental officer. I visited museums, archives and libraries. I interviewed fans and academics. In an attempt to retrace Lydia’s steps in Brighton, I toured an eighteenth–century theatre and took moody walks along the beach. I reread everything Austen wrote, including Love and Freindship (1790) and even Mansfield Park (1814). I read articles and critics and fan–fiction and learned tomes. And lordy! (to coin a phrase) how much I learned!

First, about the wider context. It had never occurred to me to wonder how twelve years of war against Napoleon’s France might impact on British society – the fear, the hardship, the uncertainty. And gosh, how little I knew about the role of the slave trade in shoring up British stately homes and cities and personal fortunes! And goodness me, inheritance and property law may seem a dry subject, but pre–welfare state, they were a matter of life and death, particularly for women. How glibly we use the phrase ‘she married for money’, as if in doing so women were prostituting themselves. In Austen’s era, what those words often mean is ‘she married him to keep a roof over her head so that she and sisters might not starve’.

Secondly, about Austen’s works. To properly understand Austen is to understand all the above, and more. It is to understand that for servants to wear white is a sign that they are paid too much; that to dance more than once with the same partner at a public ball is indeed a sign of sure attachment; that far from the pretty idyll often represented on screen, her books are populated by people who are desperate; that it was normal in those times for children to be sent away from home for economic reasons.

The more I read about Austen, her world and times, the more the books themselves opened up to me. In them, I found not only the love stories which have inspired countless films and television series (and yes, Mr Darcy is still one of the sexiest antagonists in all of literature), not only the satire and irony for which she is so rightly famous, but something more: insight into the hopes and fears of her contemporaries.

Fears of war, of change, of poverty, of uncertainty.

Hopes for love, for children, for security, for a better life.

Not so very different, then, from what we fear and hope for today.

And so to Lydia herself, and the greatest surprise of all in the process of writing about her. Lydia who is ‘vain, ignorant, idle and completely uncontrolled’ and who I very quickly grew to adore.

It is a fact universally acknowledged that writers are a little mad. When I started to sketch out Lydia’s story, I give you my solemn word that I heard her speak to me. I even heard her stamp her foot.

‘Finally!’ she cried (in my head), ‘My turn!’

Her turn not to be eclipsed by those brilliant older sisters! Her turn to prove she had just as many qualities as them! Her turn to tell her story, to be understood, to be … well, loved.

I had not expected another writer’s creation to inhabit me so completely. Lydia released something in me I didn’t even know was there and became the closest to therapy writing has ever been for me. For various (private) reasons, I hated myself as a teenager, to the point where I had blocked out years of memories. Writing Lydia, those memories came flooding back. And guess what? I liked what I remembered. Sure, I had been selfish and thoughtless, not always kind. But I had been other things too. Good things.

And, like Lydia, I had been young.

I run a writing workshop based on Lydia, in which I invite participants to write from the point of view of a minor character in one of their favourite stories. It is amazing how different the same story can appear when told from a different point of view. As familiar as Pride and Prejudice (1813) may be, it takes on a whole new light if, instead of being dazzled by Lizzie and Darcy, you pay attention to the bit players. To Mrs Bennet, desperate to see her girls provided for, or Mr Collins and his harsh, unloving father, or Mary striving unguided to educate herself. They are all in turn ridiculous, feeble, petty and selfish, but they all have their reasons for being so, and they all have their story.

Do you know the first words Lydia speaks in Austen’s novel? I didn’t.

‘I am not afraid;’

I look at this now, at what I have written. I think of my fear of confronting my past self, my fears for the uncertain future, and I repeat Lydia’s words like a mantra. It is true that she goes on to complete the sentence, somewhat ridiculously, by saying ‘for although I am the youngest, I am also the tallest.’ Well, that is Lydia, always looking for a way to measure up. The point here, surely – if you are rooting for her, rather than her sisters – is her refusal ever to be put down.

The whole exercise of retelling Pride and Prejudice shifted the light in which I saw so many things – Austen’s work, British history, the character of Lydia, myself. Perhaps that last point is a key to the enduring appeal of the great classics. They continue to tell us about ourselves, they whisper to us that though laws and customs change through the centuries, the human fundamentals of love and desire, courage and greed, selfishness and generosity, and, yes, fear and absurdity remain the same.

Writing Lydia, I rediscovered myself. And so I have another mantra, when fear and uncertainty loom:

Be more Lydia.

Be more … me.

Works cited

Primary texts

Austen, Jane (1813) Pride and Prejudice. Whitehall: Thomas Egerton.

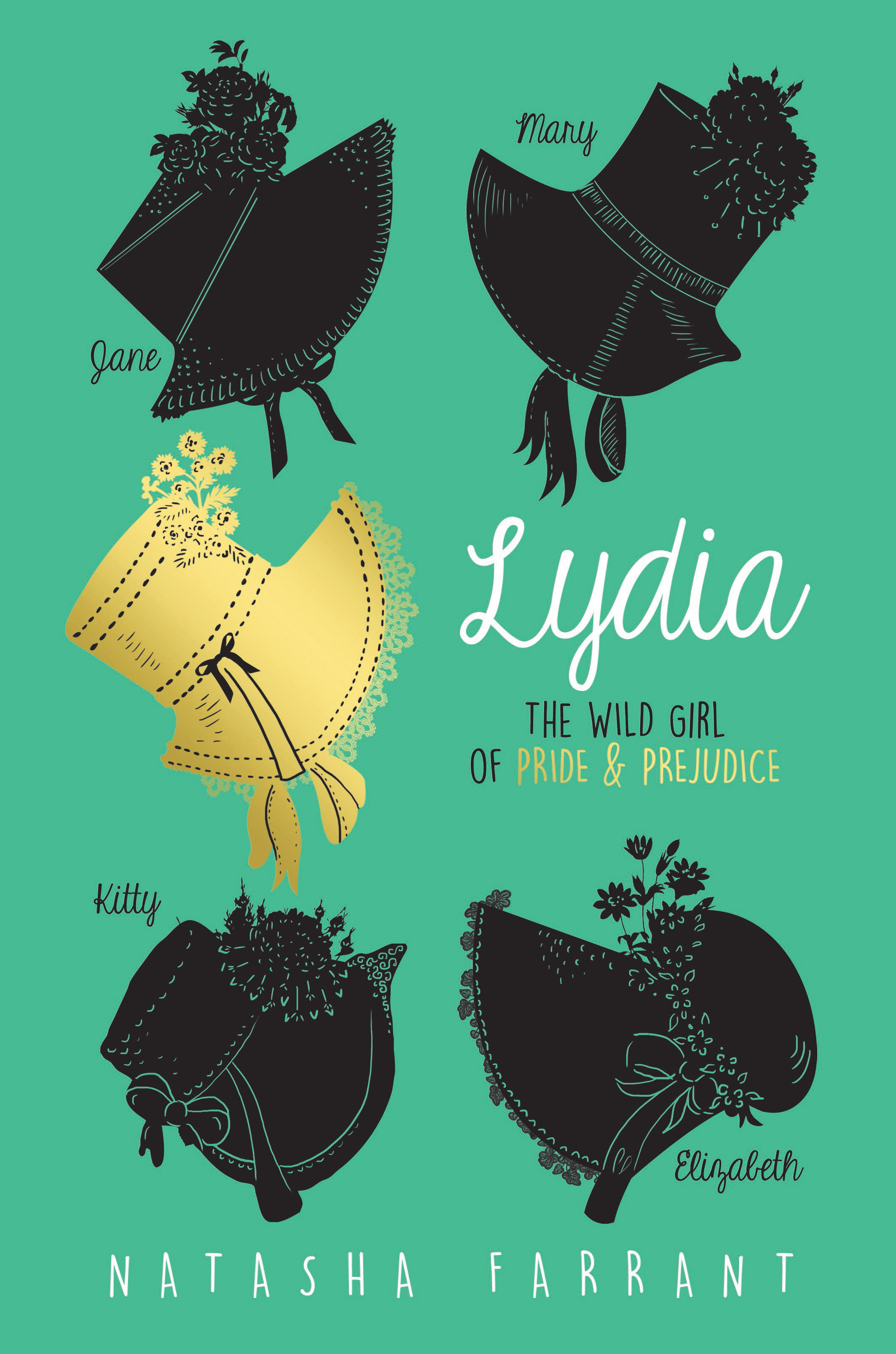

Farrant, Natasha (2016) Lydia, The Wild Girl of Pride and Prejudice. Frome: Chicken House.

Secondary texts

Austen, Jane (1790) Love and Freindship. [Unknown publisher].

–– (1814) Mansfield Park. Whitehall: Thomas Egerton.

Baker, Jo (2014) Longbourn. London: Black Swan.