One Story Many Voices

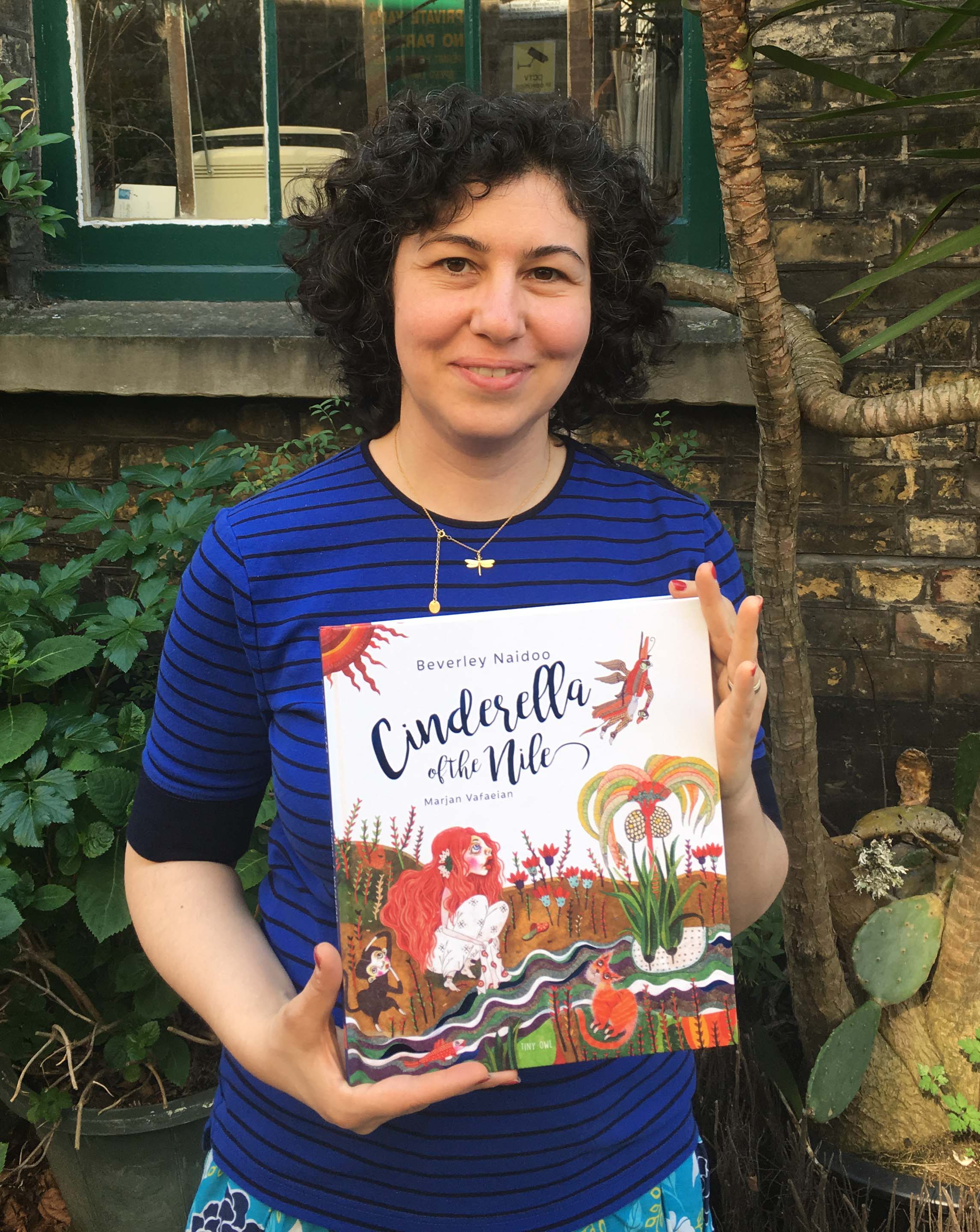

Delaram Ghanimifard

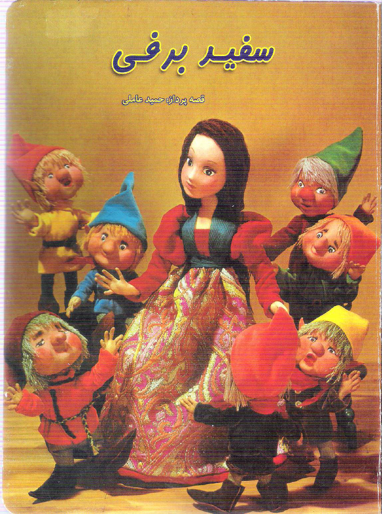

I grew up in Tehran in the 1980s during the Iran-Iraq war. It was a scary time but I always remember the safety I felt when my mother used to read me bedtime stories at night. I loved it when she read my beautiful hardcover copies of Hansel and Gretel, Cinderella and Snow White. They transported me to different worlds where good always prevailed. My father, on the other hand, would make up stories to lighten our moods – you never knew what yarn he might spin or where it might go! But it was my grandma who would tell me stories from the past, stories told by her mother and grandmother.

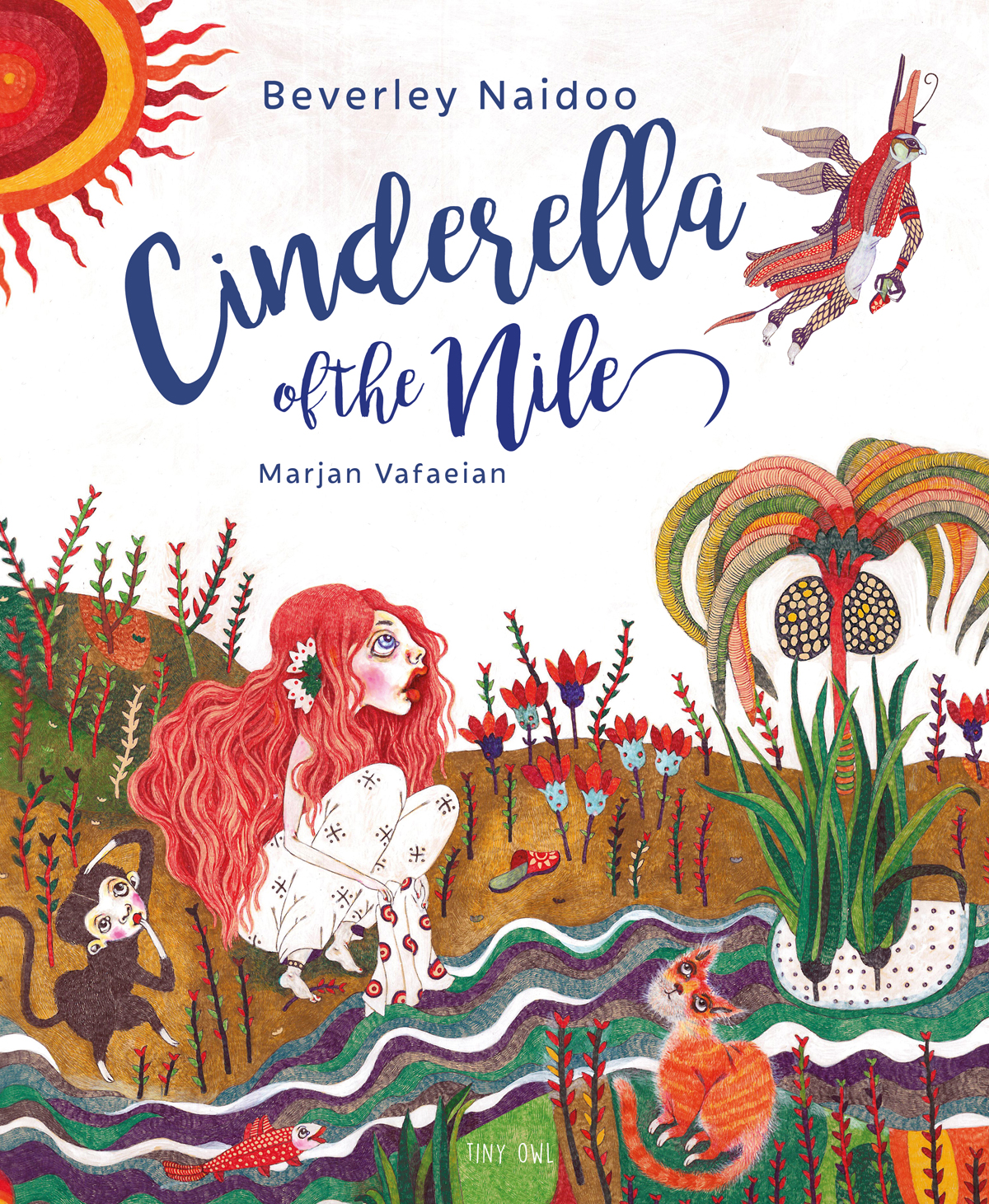

My grandma told me all sorts of stories: rhymes, funny folktales and, of course, fairy tales. It was only later that I recognised some of these fairy tales as versions of the ‘Western’ tales I knew so well. At the time, I didn’t realise that the story of the poor man in the woods with his three daughters was another version of Hansel and Gretel, or that “Mah Pishooni” was the Iranian Cinderella, and “Namaki” was The Beauty and the Beast. It made me realise that stories are dynamic. They travel like people and food. They change in their new home and adapt to their environment. Reading or hearing different versions of the same story is like finding a common language between cultures.

In the Iranian version of Hansel and Gretel, a man leaves his daughters in the forest because he’s poor and can’t support them. The children drop stones through the forest and find their way back home but the second time their father leaves them in the forest, they get lost. They dig deep underground and find their way to a magical city.

Mah Pishooni is the Iranian Cinderella. She is made beautiful by a witch because of her kindness. The witch makes her stepsister ugly because she’s so rude. Mah Pishooni attends a royal party in disguise and the prince falls in love with her. She runs back home when she realises it’s late and she has unfinished chores to do, and loses one of her shoes.

Namaki is a young girl who forgets to lock all seven doors of her home. A beast enters through one of the open doors and asks for food and a place to sleep for the night. In the morning, he demands to take Namaki home with him. Her mother says “Namaki, you were responsible for locking the doors, now you have to go!” In the beast’s home, Namaki finds a bottle that holds his life and eventually they fall in love.

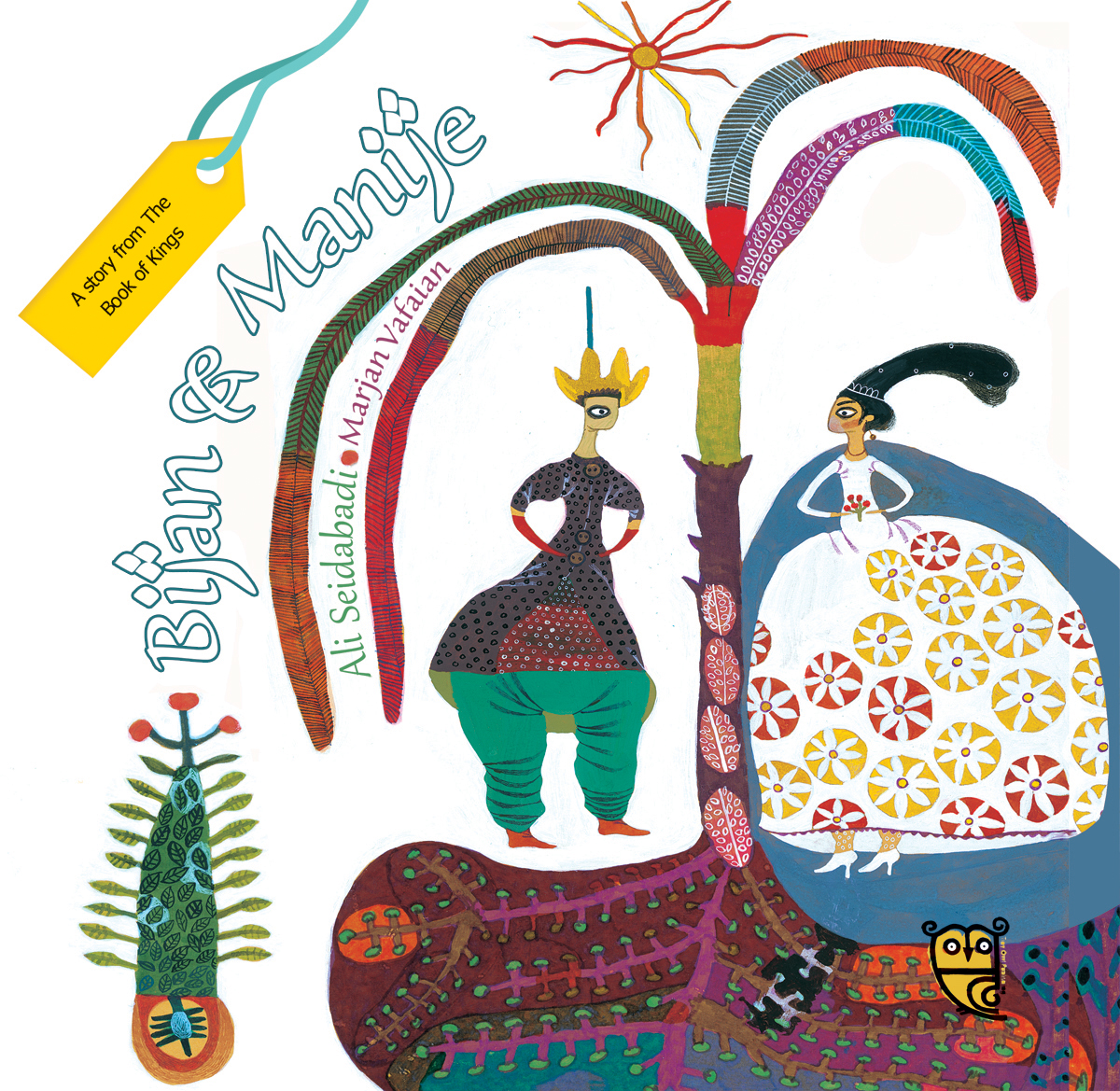

One of Iran’s most prominent poets Hafez says, “There is only one story of love and many narratives of that same story; still it is new whenever I hear it”. The same themes of good versus evil, love, jealousy, and hope permeate across cultures. Stories connect us; they remind us that we are not so different after all. Yet some of our best-known fairy tales have been co-opted by the big screen and cultural variants are little known. We wanted to create a series that paid homage to our shared global heritage and that celebrated the diverse and colourful world that we live in.

Our second fairy tale is The Phoenix of Persia (April 2019) written by storyteller Sally Pomme Clayton. This story is from Shahnameh and tells the story of Prince Zal who is born with the fairest skin and white hair. His father banishes him to the forest where he is adopted by a Simorgh, a benevolent and mythical bird which finds its parallels in the phoenix of Greek mythology and the firebird of Slavic folklore. With echoes of Snow White, this fairy tale is a story about forgiveness, the power of love and celebrating difference.

Our next fairytale is The Twelve Dancing Princesses (September 2020) by Jackie Morris, illustrated by Ehsan Abdollahi. Versions of this tale can be found in Turkey, India, Russia, Hungary and Scotland. Jackie’s haunting retelling is a fresh interpretation of the beloved Brothers Grimm fairy tale about twelve princesses who, though locked up every night, wear-down their dancing shoes much to the King’s dismay. Jackie’s dark and poetic text subverts the ending and reminds us that fairy tales change over time and for modern day audiences. Ehsan Abdollahi’s unique illustrative style in rich and delicate detail brings the story to life and perfectly encapsulate the beauty and melancholy of the story.

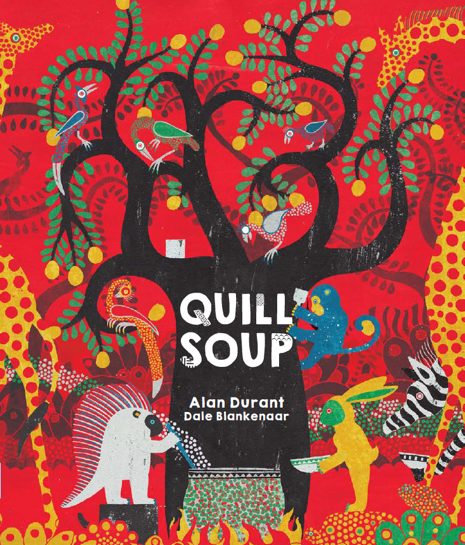

We are also publishing two folktales as part of the series: Quill Soup (May 2019) is a South African version of Stone Soup by Alan Durant, illustrated by Dale Blankenaar. In varying traditions, the stone has been replaced with other common inedible objects but our story sees Noko, the porcupine, make soup from his quills and who, through his charm and ingenuity, finally convinces the rest of the animals to share their food in order to make a meal that everyone enjoys. Miss Bandari’s Golden Heart (September 2020) by Sufiya Ahmed is a story she remembers her own grandmother telling her as a child. This traditional Indian tale of The Monkey and the Crocodile also has variants in other countries, including a Swahili version which features a shark instead of a crocodile.

As I remember my grandma’s stories, I feel a responsibility to keep them alive by telling them to my own children. As a publisher, I feel even more responsible to publish books so that children can celebrate the many voices in this world – and who will love them as much as I loved my grandma’s stories.