‘Nobody Wants to Know about That’: On the Importance of Creating Multilingual Spaces

Sabine Little

I once interviewed a group of school children about their multilingual reading experiences. They had all been hand-picked by their teacher precisely because they were multilingual, and they were reading in all their languages.

And yet, twenty minutes into our discussions, only English language books had been mentioned. I had tried hard not to steer the conversation, instead asking open-ended questions about reading in general, favourite books, and reading with family members. Finally, after I took a more direct approach, asking: ‘ … and do you read anything that is not in English?’ One 8-year-old girl replied: ‘Yeah, I read all the Harry Potter books in Bengali, but why do you want to know about that? Nobody wants to know about that.’ This response stuck with me, and I now use it frequently in teacher training and conference presentations – it spoke, in such a young child, about a certain defeat, an understanding that there were aspects of her that were not welcome, and nothing she could do about it, and it is something I have been trying to change ever since.

On closer inspection, it turned out that every single child had, in taciturn agreement, edited their multilingual identity out of the discussion, assuming that I, an adult visiting them in a formal education context, would be interested only in the part of their identity that the formal education context assesses and validates. This is a long way from the Bullock Report ‘s (DES, 1975) dream that:

No child should be expected to cast off the language and culture of the home as he [sic] crosses the school threshold, nor to live and act as though school and home represent two totally separate and different cultures which have to be kept firmly apart. {p. 286)

It also highlights how important it is that we ensure children understand that all aspects of their identity are welcome – in our schools, in our libraries, and in other public spaces.

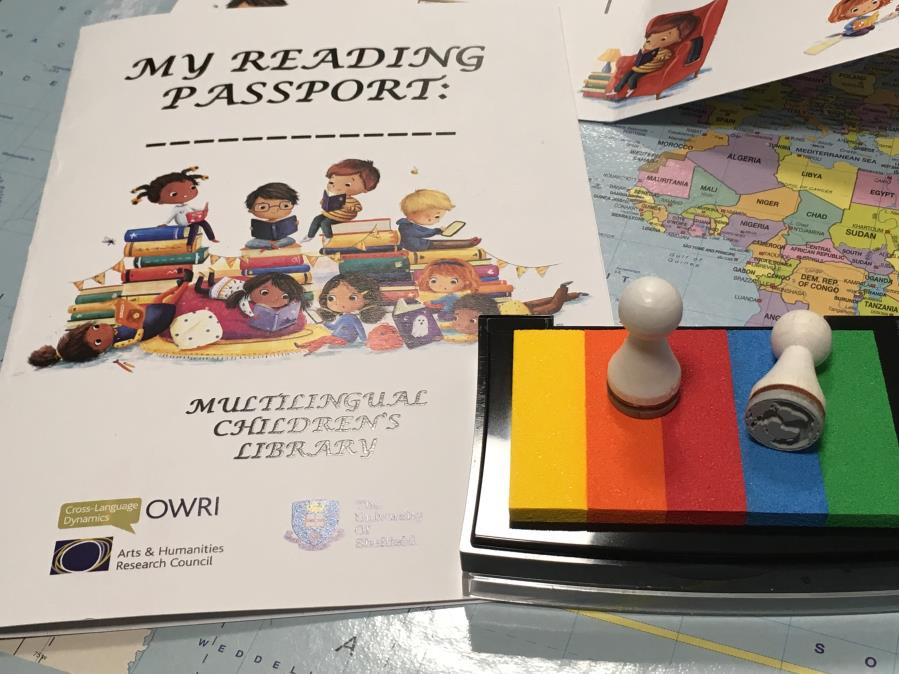

When Sheffield’s multilingual children’s library opened its doors, it adhered to a few core principles: the multilingual section would be part of the main children’s library, sharing a space in the prominent building, and there would be events that would not only support multilingual children, but also normalise multilingualism in the city. Multilingual storytelling events and multilingual readathons were frequented not just by the multilingual community in the city, but, due to being in a public space and part of the main library events, visited by passers-by, who remarked things like ‘I never heard Farsi before – it’s a beautiful language’ or ‘I stayed for three languages, it was fun trying to work out what the stories meant’. These comments, generic as they sound, play an important part in normalising multilingualism in a nation that has one of the worst reputations for foreign language learning. They also serve as important markers for social justice – public spaces serve the public, and when approximately one in five members of the public is multilingual, it is only right that the offer represents this. Parents interviewed as part of the multilingual children’s library project stated that the space meant they felt more welcome in the city as a whole, and more proud to call the city their home – a city that had made an effort to dedicate space and resource to the multilingual community. For some children, visiting the multilingual children’s library was the first time they had witnessed their home language outside the home context. Heritage language schools contributed books and expertise, organising trips to attend multilingual storytelling events, or using the library as a space to promote heritage languages and culture.

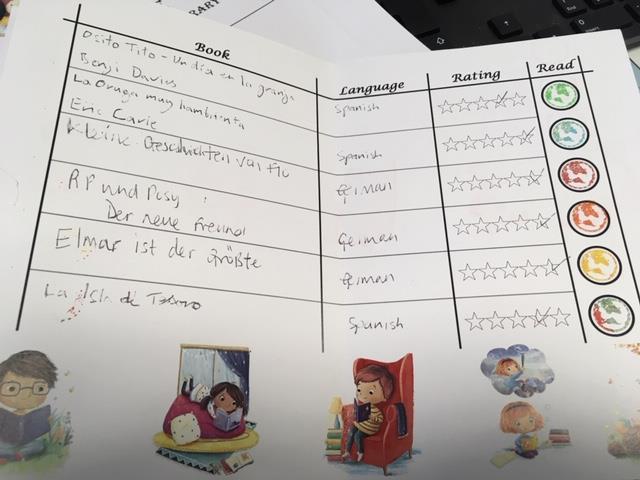

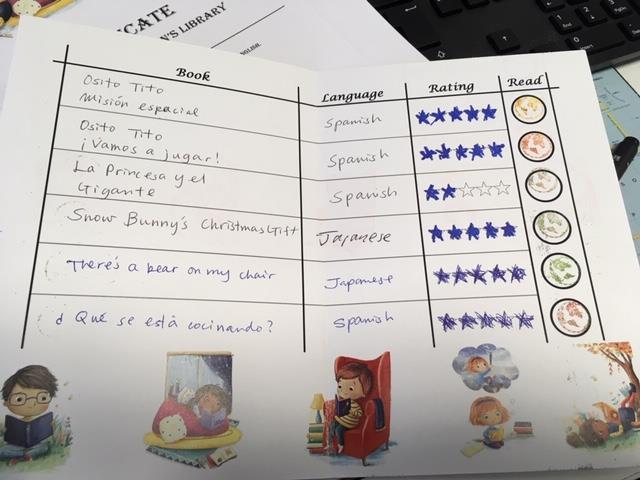

Over a series of events, children themselves became confident contributors, reading out loud in their home language to anybody who would listen, and claiming the space as theirs. The evaluation showed that the library helped children to become ‘language curious’ – a review of children’s ‘reading passports’ showed that children often borrowed books in languages other than their home language, because they were interested in exploring further, and growing their language skills. Similarly, the library is used by language learners to support foreign language acquisition.

Having a multilingual library – whether in a public library, in a school library, or in the classroom, sends an important message. It is a message of representation, certainly, of seeing books in the languages spoken by children of the city, of the school. But it also sends a message regarding space, or, more precisely, the right to take up space: space on a bookshelf, space in a classroom reading box, space in the world. This physical manifestation of space, as a representation of ideological space, matters, even to the youngest children.

Libraries, however, are not the only spaces where the normalisation of multilingualism not only matters, but benefits all, multilingual and monolingual alike. The classroom itself offers countless opportunities to validate pupils’ multilingual skills. Encouraging multilingual entries in home reading diaries, displaying multilingual book reviews, enabling children to draft work in all their languages -even if the final outcome is in English – are just some of the examples any classroom teacher can use to create multilingual spaces.

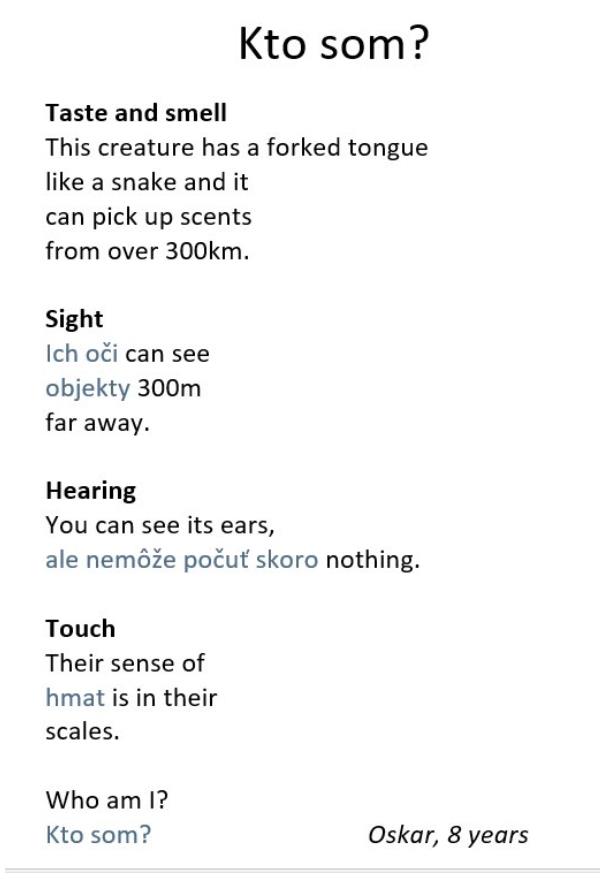

At a more advanced level, pupils can actively learn to use their language skills in their creative writing. One example for this is Oskar’s ‘creature feature’, where the eight-year-old used his English and Slovak skills to create a puzzle for his peers to guess the creature he is referring to. Such exercises raise language awareness for the whole class, and forefront pupils’ multilingual skills as valuable assets in the classroom, rather than something that ‘nobody wants to know about’. The ‘creature feature’ task is one of (currently) 29 tasks featuring on the Lost Wor(l)ds website.

Kto-som (1) – credit Oskar – Lost Wor(l)ds

The project’s premise is that children who lose their home language end up losing part of their world, and the activities are aimed at classroom practitioners – rather than language specialists – who are interested in ‘making space’ for pupils’ multilingual skills. This is not always easy in the current climate, and so all tasks are aligned to the English National Curriculum, with all activities having links to nature and sustainability.

When I talk to multilingual children, it is clear that many have developed strategies to navigate their multilingual worlds (Little, 2021), to grow their skills and confidence across all their languages. But it is also clear that they need a support net to do so, and that they rely on support from parents, teachers, schools, siblings, peers, and even society as a whole to navigate their identity development, and their sense of belonging. Whether children are reading books, producing texts, or using their full linguistic repertoire to learn – giving them the space to do so is an important component of preparing all children to live in a multilingual, multicultural world, and sends multilingual children a clear message that all parts of their identity are welcome, no matter where they are.

Works cited

DES (1975) A Language for Life (Bullock Report). London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Available online at http://www.educationengland.org.uk/documents/bullock/bullock1975.html.

Little, Sabine (2021; originally published online) Rivers of Multilingual Reading: Exploring Biliteracy Experiences among 8-13-Year Old Heritage Language Readers, Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, DOI: 10.1080/01434632.2021.1882472

Sabine Little is a senior lecturer at the University of Sheffield. She is interested in links between language, identity, and belonging, and the role of multilingualism in society. Working with families, schools, and public spaces such as libraries, she explores what it means to grow up multilingual, and developed and worked on a number of projects that explore multilingualism and identity as a social justice issue, seeking to push against the deficit model of English as an Additional Language.