My Family – The Moomins

Brian Sibley

I was an only child and a sickly child and, hence, a lonely child. Like many others such, I lived vicariously in a world of books. But which books? Certainly not most of those books featuring ‘families’.

I had read a few – by Wyss, Nesbit and Ransome – but those authors failed to engage this youngster with no siblings, few ‘friends’ and a daily life absolutely devoid of even the most commonplace adventure! The Swiss Family, the Bastables and the Walker children felt remote, as were those gung-ho, ginger-beer-fuelled larks of Julian, Dick, Anne, George and Timmy the dog.

I admit that I delighted in the escapades of William and the Outlaws and the high jinks of Jennings and Derbyshire, but that delight stemmed solely from the narrative skills of Crompton and Buckeridge, not from my identifying with (or, even, envying) their japes and scrapes – besides, the families to which those characters belonged were only ever supporting players.

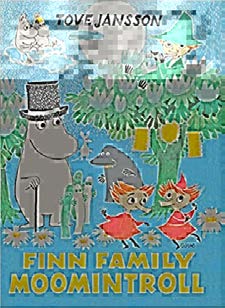

Then, in 1961, I discovered the ideal family when I stumbled on the newly published Puffin edition of Tove Jansson’s Finn Family Moomintroll – price two shillings and sixpence of my preciously guarded pocket money.

I will resist attempting to describe Moomins because (although there are those who make analogies with hippos) the only thing a Moomin resembles is another Moomin. Apart from which, if you already know what a Moomin is then you don’t need a description and, if you don’t know, then I suggest you abandon reading this article and go and find a copy of one the books instead.

I was already well aware of the Moomins since I followed their daily exploits in the comic strip in my father’s nightly copy of the London Evening News. But those strips, carefully clipped out and preserved, were three-or-four-frame ‘cartoons’ with ‘speech bubbles’; in Finn Family Moomintroll I met the same storyteller but, unshackled from the limiting restraints of the newspaper layout and the demands of syndication, I found the work of a writer of emotionally nuanced prose accompanied by some of the most alive and exciting illustrations I had ever encountered. Jansson’s drawings were in the black-and-white tradition that I loved from my copies of the Alice and Winnie the Pooh books, but – without disrespect to Messrs Tenniel and Shepard, for they remain among my gods of the drawing board – Jansson was in a category uniquely her own, for Finn Family Moomintroll and her other books in the series tell their narratives in both word and line.

My imagination was instantly seized by one such illustration: Jansson’s tantalising pictorial map of Moomin Valley (no book with a map can ever truly disappoint) and the wider landscape that is hinted at, for this was clearly but an intimate corner of a much larger world – and it was one that was irresistibly beckoning and beguiling.

I supposed that the landscape depicted on this map was purely imaginary, like the cartography encountered in other works of fiction. How, almost 60 years ago, could an 11-year-old have known that the mountains, forests and scattered archipelagos of the world of Moomins had been drawn from the Swedish-speaking Finnish author–artist’s Nordic homeland? Finland to a child in 1961 was as fantastically remote as Narnia or Middle-earth.

Inveigled into the book by this map and the quaint ‘Dear english Child’ preface (written in Moominmamma’s somewhat erratic English and her distinctive curlicue hand), I dashed into Moomin Valley (‘a small valley that was more beautiful than any they had seen that day’ [1]) and eagerly entered the tall, round, blue Moominhouse – the place where so many of the stories have their beginning and their end.

Moominhouse is a very particular residence: a haven for family (in the most hospitable definition of that word) and a refuge for outsiders. It is that place of which Snufkin, an eternal drifter, observes: ‘You must go on a long journey before you can really find out how wonderful home is’ [2]. In short, the blue tower of Moomin Valley is a shining beacon, the dependable embodiment of security and tranquillity, without those restraining locked doors and barred windows encountered in so many houses – in literature and life.

It was in the Moominhouse that I had my first introduction to the Family Moomintroll and I instantly knew that it was the kind of family to which I had long dreamed of belonging: a family unlike any other I had ever read about and one that was diametrically opposed to that into which I had been born.

I was the product of a mild-mannered father and an overanxious, mollycoddling mother: hereditary elements fertile (and, at the same time, sterile) enough to poorly nurture an only, sickly child. Mercifully, Moominland provided an escape route into a freer, happier life . . ..

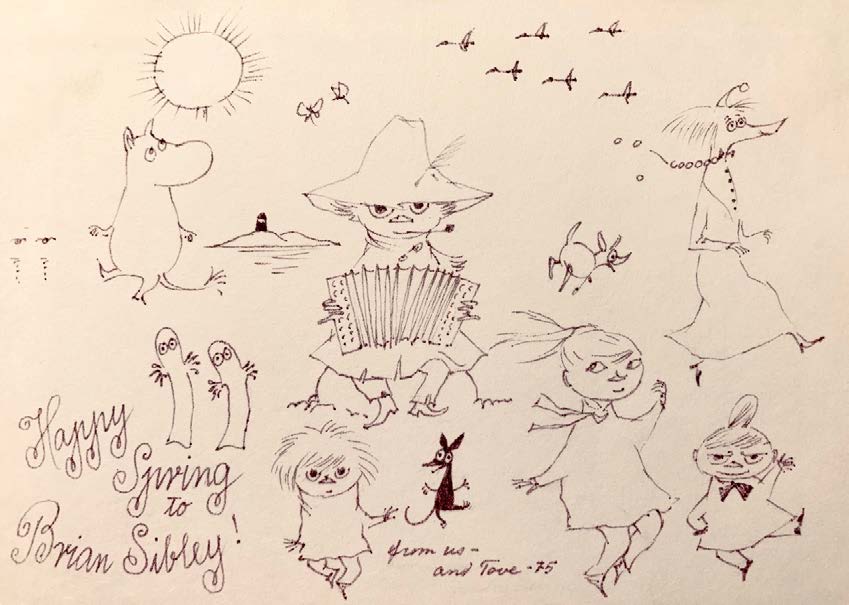

As I would later discover, through a decade of periodic correspondence with Tove Jansson, the creator of the Moomins was a highly unconventional individual from an unconventional family; and this prized individuality demonstrates itself in her writings for children and adults as a philosophy advocating the freedom and joy of self-expression, tempered with an awareness and acceptance of the individualism of others.

A greeting from Tove and her creations sent to Brian Sibley in 1975 (Brian Sibley Collection).

Presiding over the idiosyncratic Moomin clan (although ‘presiding’ is too authoritarian a word, suggestive of hierarchy and control) is an idealised model of parenthood that any child would thankfully embrace: the top-hat-wearing paterfamilias, Moominpapa, simultaneously romantic and pragmatic, a non-judgemental adult who understands the yearnings of the young because he has never forgotten the joys and perils of his own youth; and, with apron and handbag, Moominmamma, a universal cypher for motherhood (‘Mama will know what to do’ [3]) supremely calm, never censorious and a constant dispenser of unrestricted and non-prescriptive love, comfort, understanding and wisdom.

Moomintroll, their son, is (no doubt as a result of his parentage) loving, caring and sensitive; he is naïve, yet inquisitive and has that sharply attuned sense of wonder at the world around him that the world-weary adult identifies as a marker of a happy childhood. Although (as I was) he is a solitary child, Moomintroll is part of an ever changing, expanding and contracting, gathering of kith and kin – some invited, others not – all received and accommodated by his parents and, as a result, enriching his young experience of life.

Within the first few pages of Finn Family Moomintroll, the younger me recognised Jansson’s unconditional credo:

Moomintroll’s mother and father always welcomed all their friends in the same quiet way, just adding another bed and putting another leaf in the dining-room table. And so Moominhouse was rather full – a place where everyone did what they liked and seldom worried about tomorrow. [4]

What, in that description, was there not to like – and desire?

Jansson’s text rarely devotes time to descriptions of Moomintroll’s extended family: having given their names (often suggesting personality and, where preceded by the definite article, singularity – as with The Joxter and The Muddler), she draws them and leaves her readers to make what they will of their nature and temperament.

The primary cast of characters becomes the young reader’s close companions: and their diverse personalities are, if nothing else, a passport to the learning of tolerance. Every Moomin reader will have a favourite: my own (after Moomintroll) being Snufkin, the wanderer forever following the flowing river to the strange places for which he longs. ‘I have a plan,’ he tells Moomintroll before setting out on one of his enigmatic quests, ‘But it’s a lonely one, of course’ [5]. Of course . . .. And, of course, one spring morning he will return with his battered hat and his tobacco pipe and will whistle under Moomintroll’s window and new adventures will follow.

The only-ever friend of my youth was a Snufkin whose close friendship was entirely dependent on being willing to forego closeness if and when a lonely plan came into his head. Jansson writes:

Moomintroll was left alone on the bridge. He watched Snufkin grow smaller and smaller, and at last disappear among the silver poplars and the plum trees. But after a while he heard the mouth organ playing ‘All small beasts should have bows on the tails,’ and then he knew his friend was happy. [6]

Your favourite character might be the timid, clumsy Sniff who nevertheless has his moments of triumph (such as finding the mysterious Hobgoblin’s hat); or Moomintroll’s inamorata, the loving, but foolishly vain Snorkmaiden; or her stickler of a brother, the Snork.

But there are so many others: the curmudgeonly Muskrat, The homely Mymble, The Mymble’s Daughter and her sister, the impish Little My; those shy and anxious little creatures Toft, Toffle and Ninny, the Invisible Child and, in contrast, that mischievous knock-about duo, Thingummy and Bob. Nor must we forget assorted (and highly strung) Fillyjonks and lugubrious Hemulens – the latter known for their predilection – regardless of gender – for wearing dresses.

You may, depending on your temperament, even be enticed by the inscrutable and unfathomable Hattifattners or, perhaps, share the soul-stirring anguish of the lonesome Groke, doomed forever to bring cold and darkness to wherever there is warmth and light.

With good evidence, I can surmise that Tove Jansson’s favourite character was Too-ticky, inspired by the author’s same-sex life partner of over 60 years, Tuulikki Pietilä (or familiarly, ‘Tooti’), the American-born Finnish sculptor and a pioneer in graphic arts. As noted earlier, Jansson was an unconventional individual and the broad and open-mindedness that imbues her books is a reflection of her openly shown love for her Tooti. Although quite a few years before the adolescent struggles with my sexuality, I know – in rereading Jansson’s stories – that her non-judgemental portrayal of friendships shaped my personal ideology.

It is also clear that Tooti influenced Too-ticky’s philosophy of life and her Walt Whitman-like wisdom: ‘It’s a song of myself . . .’, she explains to Moomintroll of a tune she is whistling,

A song of Too-ticky . . .. The refrain is about the things one can’t understand. I’m thinking about the aurora borealis. You can’t tell if it really does exist or if it just looks like existing. All things are so very uncertain, and that’s exactly what makes me feel reassured. [7]

The Moomin family and their friends are repeatedly caught up in happenings, sometimes trivial, sometimes of consequence and frequently elemental: great floods, all-enveloping winter blizzards, lightning storms, earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. As Jansson notes:

Very often unexpected and disturbing things used to happen, but nobody ever had time to get bored, and that is always a good thing.’ [8]

Boredom is never permitted in Moominland.

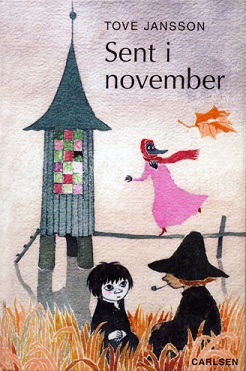

I often revisit the Family Moomintroll to relive their myriad exploits, large and small, at home and at sea (even those told in the one book in which the family never actually appear, Moominvalley in November), because they allow my younger self to run free once more and embrace life.

I pore over, as I did when I first discovered these books, Jansson’s illustration in Finn Family Moomintroll of the Hattifatteners’ secret meeting place, their wavy, vacant-eyed forms drifting out from exotic vegetation to observe the Hemulen botanist who, magnifying glass in hand, has unwittingly strayed onto hallowed ground; or in Moominland Midwinter, the dramatic illustration of Moomintroll unexpectedly awake and anxious in the snow-bound house while his mother sleeps and with the moon flooding the room with pale light and ‘the cut-glass chandelier softly jingling to itself’; or, again, the drawing in Comet in Moominland of Moomintroll and his friends traversing the dried-up ocean bed on stilts casting long shadows on an alien, Daliesque landscape with a wrecked galleon suspended amongst the once-submerged rocks and the comet of the title relentlessly approaching.

I also return to these books for their perpetual challenge – gently demanding that, like the Moomins, I seek a fuller awareness of my world, my place within it and a better appreciation and acceptance of those with whom it is shared. Beyond that, there is the imperative to respond to Tove Jansson’s perpetual call to adventure, as announced by Moominpappa’s oldest and closest friend, the inventor Hodgkins, at the conclusion of The Exploits of Moominpapa:

‘Silence!’ cried Hodgkins and raised his glass. ‘To-morrow . . ..’

‘To-morrow,’ repeated Moominpapa with shining eyes.

‘To-morrow the adventures begin anew,’ Hodgkins continued . . ..

‘Not to-morrow, to-night!’ shouted Moomintroll.

And in the foggy dawn they all tumbled out in the garden. The Eastern sky was a wonderful rose-petal pink, promising a fine clear August day.

A new door to the Unbelievable, to the Possible, a new day that can always bring you anything if you have no objection to it.’ [9]

And what objection could one possibly offer – especially, if we are to be in the company of Moomintroll and family?

Acknowledgements

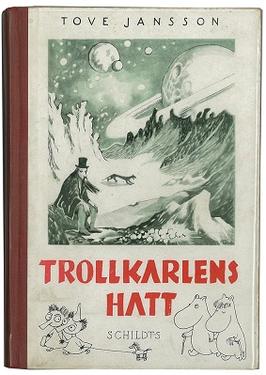

Covers in Swedish are first editions. Covers in English are those published by Sort Of Books.

Notes

[1] The Moomins and the Great Flood, 1945, first translated and published in English in 2005.

[2] Comet in Moominland, 1946; English version, 1951; Chapter 8.

[3] Ibid., Chapter 9.

[4] Finn Family Moomintroll, 1948; English version, 1951; Chapter 1.

[5] Ibid., Chapter 1; Chapter 7.

[6] Ibid., Chapter 1; Chapter 7.

[7] Moominland Midwinter, 1957; Chapter 2.

[8] Finn Family Moomintroll, 1948; English version, 1951; Chapter 1.

[9] The Exploits of Moominpapa, 1950; Epilogue.

Moomin Books

Hyperlinks are to Wikipedia.

The Moomins and the Great Flood (Originally: Småtrollen och den stora översvämningen) – 1945.

Comet in Moominland (Originally: Kometjakten/Kometen kommer) – 1946.

Finn Family Moomintroll, Some editions: The Happy Moomins (Originally: Trollkarlens hatt) – 1948.

The Exploits of Moominpappa, Some editions: Moominpappa’s Memoirs (Originally: Muminpappans bravader/Muminpappans memoarer) – 1950. Moominsummer Madness (Originally: Farlig midsommar) – 1954.

Moominland Midwinter (Originally: Trollvinter) – 1957.

Tales from Moominvalley (Originally: Det osynliga barnet) – 1962 (Short stories). Moominpappa at Sea (Originally: Pappan och havet) – 1965.

Moominvalley in November (Originally: Sent i november) – 1970 (In which the Moomin family is absent).

All the books in the main series except The Moomins and the Great Flood (originally: Småtrollen och den stora översvämningen) were translated and published in English during the 1960s and 70s. This first book would eventually be translated into English in 2005 by David McDuff and published by Schildts of Finland for the 60th anniversary of the series. A later 2012 version of the same translation, featuring Jansson’s new preface to the 1991 Scandinavian printing, was published in Britain by Sort Of Books, and was more widely distributed.

There are also five Moomin picture books by Tove Jansson:

The Book about Moomin, Mymble and Little My (originally: Hur gick det sen?) – 1952.

Who Will Comfort Toffle? (originally: Vem ska trösta knyttet?) – 1960.

The Dangerous Journey (originally: Den farliga resan) – 1977.

Skurken i Muminhuset (English: Villain in the Moominhouse) – 1980.

Visor från Mumindalen (English: Songs from Moominvalley) – 1993 (No English translation published).

Websites

Moominpapa. https://www.moomin.com/en/characters/moominpappa/.

Moominmamma. https://www.moomin.com/en/characters/moominmamma/.

Moomintroll. https://www.moomin.com/en/characters/moomintroll/.

Snufkin. https://www.moomin.com/en/characters/snufkin/.

Too-Ticky. https://www.moomin.com/en/characters/too-ticky/.

Other characters by clicking on their portrait in the graphic. https://www.moomin.com/en/characters/.

‘A Guide to the Moomin Characters’. https://www.panmacmillan.com/blogs/books-for-children/the-moomin-characters.

Brian Sibley is a writer and broadcaster whose many interests include children’s literature and the art of illustration. Artists and writers of childhood classics about whom he has written include Lewis Carroll, A.A. Milne and E.H. Shepard, C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien and Pauline Baynes. He corresponded with Tove Jansson for several years and, in 2015, contributed the afterword to a new Finnish edition of Tolkien’s Hobitti eli Sinne ja takaisin (The Hobbit) with Jansson’s illustrations.