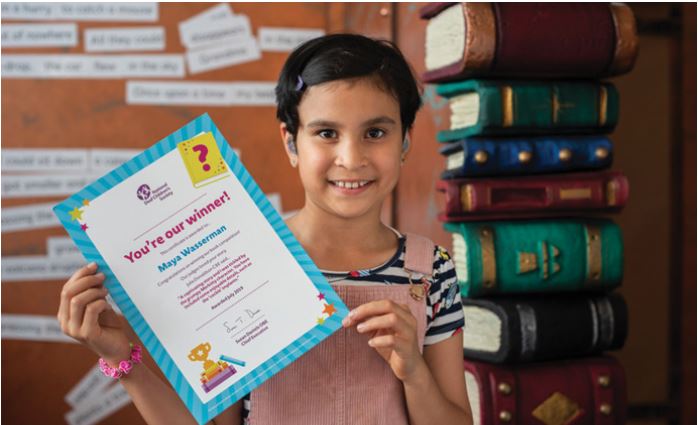

Maya Wasserman’s story shows deaf children they can achieve anything

A nine-year-old deaf girl’s story shows the way disabled characters should be seen in children’s books

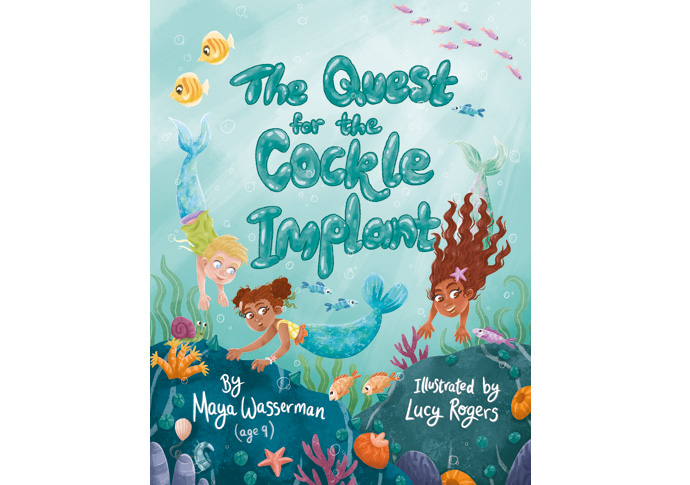

In the children’s book, The Quest for the Cockle Implant, a deaf mermaid called Angel loses one of her “cockle” implants , so she, her sister and a friend travel on an adventure through the sea to find it.

It was written by Maya Wasserman, who was nine when she wrote it. She is deaf, as is the book’s illustrator, Lucy Rogers.

The result of a storytelling competition run by the National Deaf Children’s Society and judged by Julia Donaldson, author of The Gruffalo, The Quest for the Cockle Implant took first prize.

Ms Donaldson described the story as “captivating” and has spoken of the importance for children to be able to relate to characters in books. “I’ve seen first-hand how powerful it is for a child to have their lives and their experiences reflected in what they read – to be able to say ‘There’s someone like me!’” she has said.

This is echoed by Maya who hopes her book will help others.

“I think it is so important because deaf children don’t really see themselves as deaf,” she says.

They just see themselves as different from other people; they maybe don’t like it because they maybe want to be like the other people, so then when books about deaf children come out like mine they will see: ‘oh there’s other people in the world like me’.

Children’s book consultant and author Alexandra Strick believes there has been progress with regard to meaningful depictions of disability in children’s books.

“I’ve been working in this area for more than 25 years and the picture has certainly improved in many ways,” she says.

For starters, there are simply more books featuring disabled characters, but more than this – there are also far more authentic representations.

The book industry is recognising the need to ensure more books feature disability, but also that they do so in a diverse and authentic way and that the book landscape includes both books ‘about’ disability or with disability as a core to them, but also features disabled characters casually.

Ms Strick added:

Historically, books featuring disabled characters were few and far between and disability was often ‘problematised’, so seen as a problem to be overcome: the disabled person perhaps seen as a burden or someone to be pitied. Disability was often seen by the non-disabled person’s perspective.

Dr Rebecca Butler, who is a writer and commentator on children’s literature and is a wheelchair user, also wants to see more three-dimensional disabled characters in books.

She says:

If the only thing about the character is their disability then that negates a valuable story. Incidental depiction is much better if it can be achieved. It’s mainly about three-dimensional, not perfect characters. And for me, it’s about allowing negative feelings towards their disability to be depicted.

It’s important that children, particularly children with disabilities, are able to acknowledge those feelings happen.

Make disabled characters three-dimensional, we are not only our disability. And we are also not always in good moods.

She added:

Disabled kids need to see disabled adults who are listened to in books. If they see a disabled adult in a book they might think: ‘maybe I could too’. If there aren’t any characters there won’t be any ‘maybe I coulds’.

There is, she says, the fact that non-disabled children can benefit from encountering disabled characters in books, leading them to have a “more informed and positive view of people with impairments”.

So how can more change happen?

Ms Strick believes that the book industry needs to publish, employ and consult disabled people more, to help ensure authentic representations.

“Where one is not writing from experience I think early research and consultation with those who have lived experience is one of the keys,” she says.

One of the organisations I co-founded is Inclusive Minds which has a network called the Inclusion Ambassadors who are people with lived experience willing to share it with book creators.

Dr Butler, who is a trustee of the International Board on Books for Young People (IBBY) which stages a biennial event promoting books with portrayals of disability, would also like to see more disabled people working in publishing.

Publishing houses, she says, should “talk to disabled people and make better opportunities”.

She adds: “Talk to disabled people about representation and they will tell you instantly if a character feels wrong to them.”

According to The National Deaf Children’s Society, there are 50,000 deaf children in the UK.

Maria Chambers, director of services and innovation at the National Deaf Children’s Society, believes that books like Maya’s can bring about real and lasting change.

“Children’s stories should be as diverse as the young people who read them,” she says.

It’s really important for deaf children to see themselves and their experiences in the stories they love and grow up with.

Maya’s book casts a really positive light on deafness, and we’re so proud to have worked with her on this book.

Not only is Maya showing a fantastic portrayal of deaf characters in her book, but is showing other deaf children that there is nothing they can’t achieve.

- The Quest for the Cockle Implant is £6.99 plus postage and packing and is available from The National Deaf Children’s Society, www.ndcs.org.uk/childrens-books

- For more information on The National Deaf Children’s Society go to www.ndcs.org.uk/ or call 020 7490 8656.

- Inclusive Minds www.inclusiveminds.com

- International Board on Books for Young People www.ibby.org

- Many thanks to Jane Clinton for permission to repost her article. To read the original article go to http://camdennewjournal.com/article/sound-reasoning