Magic in the Mundane: A Glimpse at the Picture-Book Art of Anthony Browne

Ian Dodds

Take a look at almost any of Anthony Browne’s picture books and they begin with a single image of a child – human or ape. They are seemingly alone although the images hint at the potential for escape and friendship through the power of imagination.

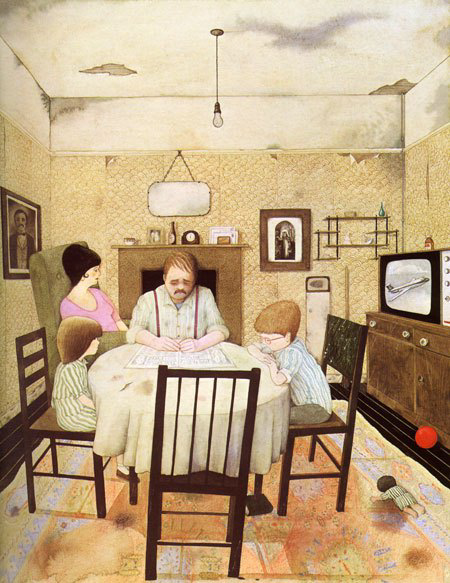

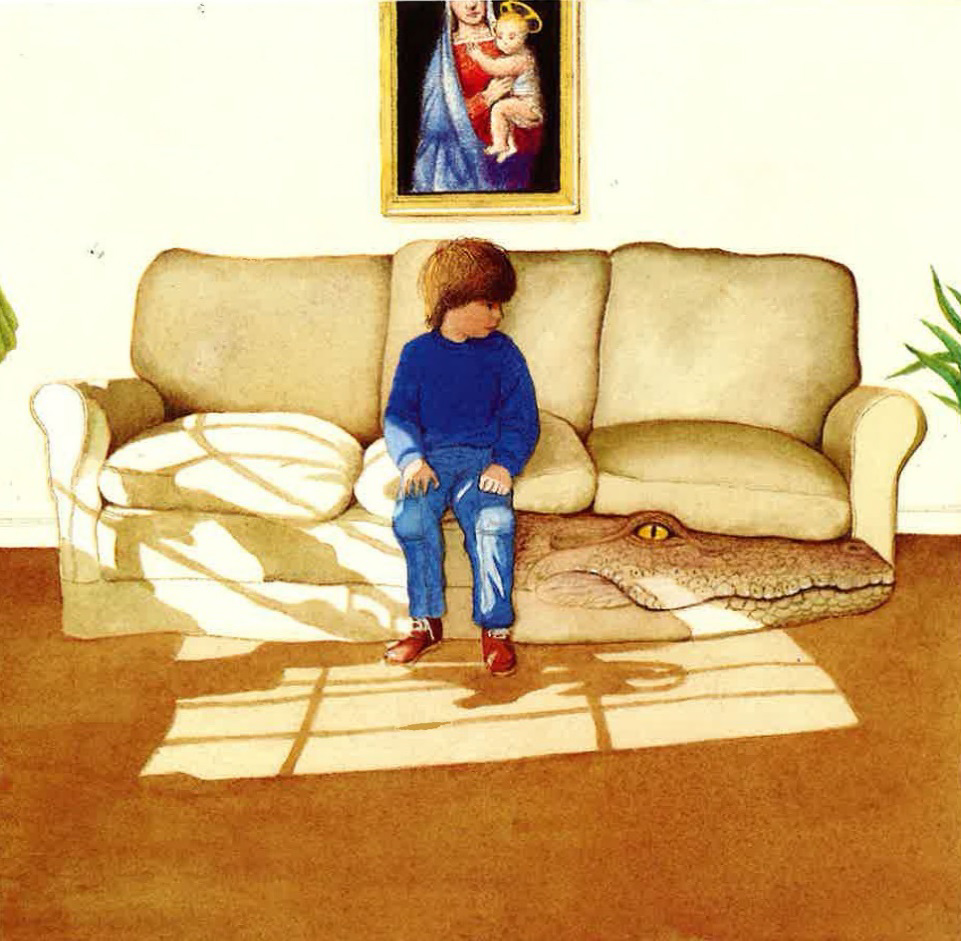

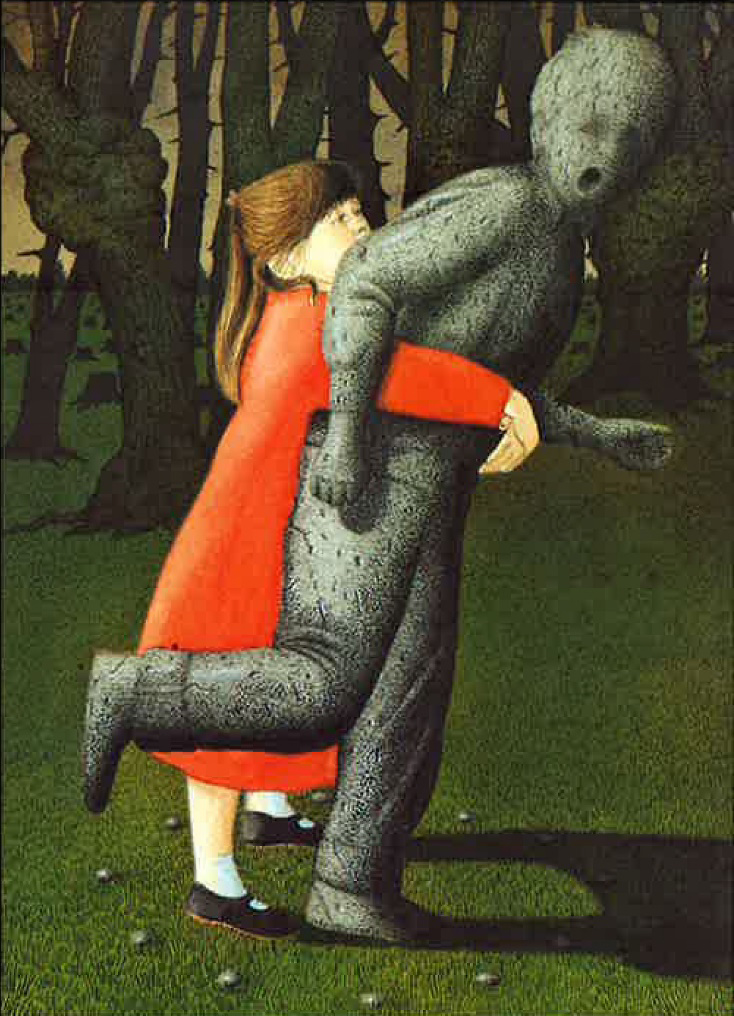

Escape from loneliness is a continual theme in Browne’s picture books; as are absent fathers, disconnected families and longed-for friendships. These themes are reinforced by the domesticity of his picture-book settings. His kitchens and bedrooms, streets and parks, are familiar to us; however, it is not always the cosy domesticity we expect, and neither are they the cosy family relationships we have come to know in picture-book fiction. In fact, they are often uncomfortable spaces, tinged with unhappiness and the threat of menace to come. This undercurrent of darkness and Browne’s deftness to deal with complex and difficult themes permeates his art and arguably gives his picture books their enduring appeal.

Children are more than capable of coping with all kinds of stories; it’s adults who are threatened by the darkness in children’s books. But it has a place: an essential place. If we insist on telling children that everything in the garden is lovely, we are doing them a disservice. (Browne, 2009a).

Meaning-laden visual clues are a signature in Browne’s picture books.

I see Hansel and Gretel as a breakthrough book for me, and one of the reasons is because I started to apply meaning in the hidden details. Whereas in previous books I had treated them as little more than doodles in the background, in Hansel and Gretel I employed them as subtle aids in telling the story. Not only do they re- enforce the main narrative; they also offer an insight into extra narrative information that isn’t expressed in the text. (Browne, 2009a)

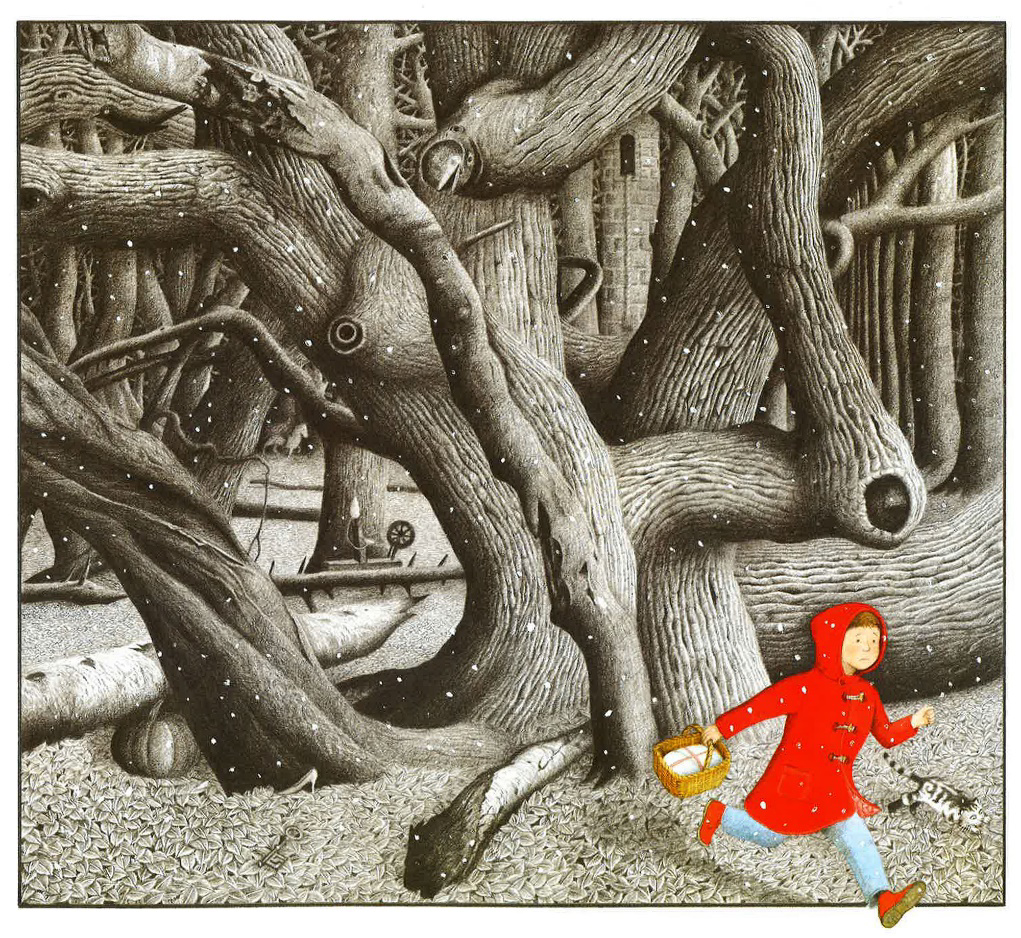

These visual clues rely on us having cultural knowledge and competence in other texts and discourses: fairy tales, fine art, cinema and comic books. Browne’s illustrations are accessible on a number of levels, but place some reliance on the audience’s inter- textual competence to understand the visual clues that he carefully and deliberately places there. Fairy-tale motifs are particularly important in his work. They are amongst the cultural currencies that are more likely to be grasped by children and deliver the elements of darkness that he so enjoys. Such references are spread throughout Into the Forest (2004), which tells the story of a boy anxious to be reunited with his father (illus. 4). Black and white illustrations are used for the forest scenes where he meets a cast of fairy-tale characters. The characters are all notable for their absent fathers: Jack, Goldilocks, Hansel and Gretel. Other fairy-tale images are woven into the black- and-white images that heighten the fear and anxiety we share with the boy as he makes his quest to his grandmother’s cottage. In one image the twining branches of a tree incorporate a pumpkin, a spinning wheel and Rapunzel’s tower alongside other fairy-tale objects placed there to prompt us to look more carefully and search for inter-textual meaning.

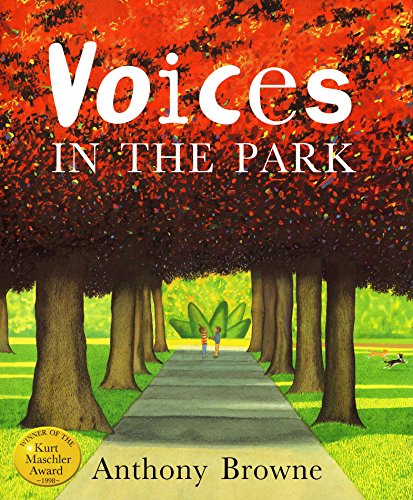

This type of magical realism has its roots in folklore and fairy tale. It has its genus in South America where it was a device used by writers and artists struggling against oppressive and despotic regimes. The magic opposed a reality that the writer or artist found unsatisfactory, restrictive or uncomfortable and which needed to be disrupted. This desire is clearly replicated in Browne’s work: we see it in the struggle to escape an oppressive family in Hansel and Gretel or to reignite a loving family relationship in Gorilla. It is a central theme in Voices in the Park (1998) which is itself are working of an earlier Browne book, A Walk in the Park (1977). In the book Charles and his mother take a walk in the park with their pedigree Labrador, Victoria. There they share a bench with a young girl called Smudge, her father and their mongrel dog, Albert. The two families are from different backgrounds. We are shown this not only in the names they are given, their dress and body language, but also in the colour palettes, tones and fonts that Browne uses to voice each character. Charles is lonely, living a sheltered and restricted existence under the control of his mother. He wears a buttoned-up duffle coat and is most often seen standing in his mother’s shadow. Her hat is ever-present in the grey clouds, the shape of a leafless tree, and on the tops of the lampposts that line the path that Charles seems unable to leave.

Central to these magical illustrations is the desire for and achievement of change. This is only hinted at for Charles.

I’m good at climbing trees, so I showed her how to do it. She told me her name was Smudge – a funny name, I know, but she’s quite nice. Then Mummy caught us talking together and I had to go home. Maybe Smudge will be there next time?

All that is left of their joyful encounter is a red flower that Charles gives to Smudge. We know that the flower will eventually fade, but the magical touches in the final illustration gives us hope that this will not be their last time together in the park.

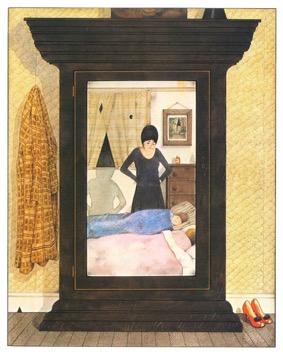

The potential for change and the whole transformative process is a significant element in Browne’s illustrations and magic realist approach. His illustrations guide us to better understand his characters’ changing views, wishes and feelings, and prompt an emotional response from us. We see this first in Piggybook (1986) where the roses on the wallpaper gradually morph into pig faces as Mr. Piggot and his two sons become greedier and more chauvinistic towards their mother; but it is perhaps best seen in Changes (1990) where Joseph must come to terms with the addition of a new baby sister to the family.

That morning his father had gone to fetch Joseph’s mother. Before leaving, he’s said that things were going to change.

What Changes also includes is Browne’s trademark references to fine art and in particular his nods to the Surrealist art of Salvador Dalí and René Magritte. Surrealist interest in the marvellous appearing in everyday life, and the transformation that comes from seeing things in different ways, are commonplace in his books.

I believe children see through surrealist eyes: they are seeing the world for the first time. When they see an everyday object for the first time, it can be exciting and mysterious and new. (Browne, 2009a)

Socks hanging on a washing line are transformed into a Dalí-esque animal skull; a hosepipe becomes an elephant’s trunk; a scrubbing brush becomes a hedgehog; and a plant pot develops a bird-like beak. Similarly, Magritte’s bowler-hatted men are found throughout Browne’s picture books from early works, such as Through the Magic Mirror (1976) on to the award-winning Zoo (1992) and beyond — at least until the Magritte estate intervened following the publication of Willy the Dreamer (1997) and told him to stop. In earlier works, the images tend to appear in the foreground or the background without meaning; but in later books their inclusion points to the sub- textual narrative of the story.

I want my books to have a point and so I try to use the transformations or strange happenings to try to tell us something that the words don’t. (Browne, 2010).

That we may not understand the hidden meaning of these fine art or cultural motifs does not mean that they do not communicate something to us; nor does it diminish the power and enjoyment of the story. For those of us who derive additional meaning from his images, Browne’s magical touches allow for a fuller and more challenging reading of the book. For us all, the magical realism of his artwork encourages us to embrace a new way of looking and seeing. He creates a careful path in his illustrations that steers us through the narrative but which also teases us, like Charles in Voices in the Park, to venture from the path, to free our imaginations and look creatively, so that we become more curious as readers, become more skilful at questioning, and more adept at walking a little way in somebody else’s shoes.

The best picture books are ones that leave a gap between the pictures and the words – a gap that is filled by the reader’s imagination. (Browne, 2009b)

References

Browne, Anthony (2006) – Anthony Browne quoted in A Life in Books: Anthony Browne in The Guardian: 4 July 2006.

–– (2009a) – Anthony Browne quoted in The Surreal Brilliance of Anthony Browne’s Art in The Guardian: 10 June 2009.

–– (2009b) – UK Children’s Laureate acceptance speech: 9 June 2009.

–– (2010) – Anthony Browne quoted in An Interview with Anthony Browne for the Cooperative Children’s Book Centre: 26 June 2010.