Magical Reality in Children’s Fiction

Penny Thomas

As Maria Merryweather arrives at her estranged uncle’s west-country mansion of Moonacre Manor she thinks for a fleeting moment that she sees a little white horse at the far end of a glade in the moonlit woods. But her startled guardian assures her that no such creature exists on the estate.

I recently chaired a seminar at the London Book Fair on ‘The new Welsh magical realism in children’s publishing’. Thanks to some kind fairy godmother the event went well, but I admit I’m still struggling with comprehending magical realism in relation to children’s books.

A quick Google gives many, often defensive, definitions of magical realism. It is most usually described as the appearance of an impossible or magical event in an otherwise entirely serious and realistic adult novel, most notably in the novels of Gabriel Garcia Marquez, such as the shattering moment when the blood of a murdered son flows around corners and up steps to end at the feet of his mother. A truth expressed in fictional terms where fiction allows the impossible to happen, maybe. We are admonished that this is quite different from that fantasy stuff, which is mere escapism, whereas it is the duty of adult fiction to engage with the real world and try to order or reorder the experiences it retells.

But in this article I’d like to step away from the tautological world of ‘entirely serious and realistic adult fiction’ and give the slip, at least for a while, to the question of escapism (who is against escapism anyway apart from a jailer, it has been said). Instead I’m setting sail for the more enticing islands of magical reality in children’s fiction, where there are mercifully fewer attempts to kill the magic stone dead before it can be officially allowed to exist.

I mean, if a pumpkin can turn into a golden carriage, and back again at midnight, what can’t happen? By and large, though, fairy stories fit their own internal reality, and the grooves of the much-told tales. For other stories of magical reality, there needs to be a way in: a door to knock.

Delving back into twentieth-century British fiction to explore this further, I find myself immediately in that little-used room in the old house with the wardrobe. Open the door, peep through it, push between the mothballed fur coats (I’ve never smelt mothballs but mention them and I’m in that wardrobe) and you might just see a lamppost, and a glitter of snow on branches. It’s that longed-for doorway into another world: scary, possibly dangerous, but compelling.

But of course it didn’t start with the wardrobe door. The fairy door has been around a very long time; the magical entrance to Annwn, the otherworld as the Welsh have it, has opened or closed at will (generally the faery will) to trap the unwary and release them again after fruitless enchantment, typically lasting a year and a day – and that’s if they are one of the lucky ones. Time of course is different in faery lands, and it’s wise not to eat or drink a drop if you ever want to escape.

To go back to C.S. Lewis, the device becomes ever more involved. In The Magician’s Nephew (1955), prequel to The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (1950), he creates the ‘wood between the worlds’, where wearers of certain magical bracelets can choose which world they enter by jumping in different pools with the wood, a sort of quiet place with a hum….

Just as important of course, is sustaining the magical reality so carefully created. To step back through the wardrobe door one last time, through time, into a small Oxford pub, Tolkien was reportedly outraged when his fellow Inkling C.S. Lewis allowed Father Christmas to blunder his way into the magic of Narnia, and even more bizarrely, furnish the children with weapons as Christmas presents.

‘It simply will not do,’ he warned. And he had a point.

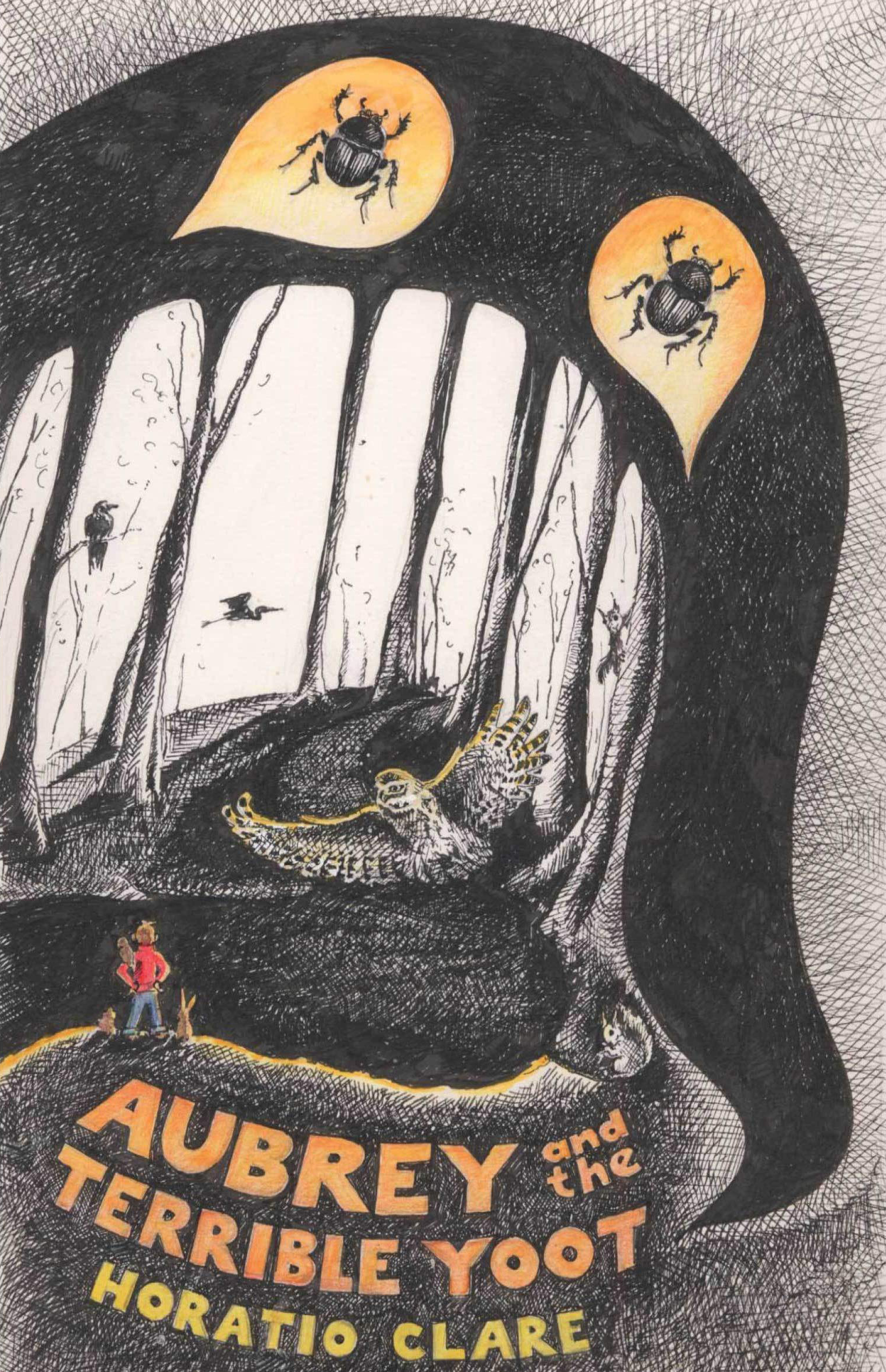

At this point our whole story hangs in the balance. Aubrey even takes hold of the curtains; he is about to shut them on this unlikely but demanding bird.

But, as Clare explains in rather brilliant footnotes, the talking owls are to him an extension of the natural world, rather than a move away from it:

Oh-ho, you may be thinking, a story with talking animals in it. How anthropomorphic. … However as you will see, the philosophy of this story is closer to animism. … Animism says humans are not the centre of the universe because everything in nature has a soul or a spirit, and that plants and rivers and owls have their own existences in the same way you do. (This is why you sometimes overhear people like Suzanne [Aubrey’s mother] say, ‘Hello, woodpigeon’.)

To backtrack a little, the talking owl arrives just after the young hero, Aubrey, has drawn inspiration from the tale of Perseus and the Medusa in his book of Greek Gods, Myths and Monsters. He takes Perseus for a role model to help him fight the invisible enemy of depression (the terrible Yoot of the title) which he believes is attacking his dad. We are told right away that this is a battle he can’t win, but the story, the use of myth and magical understanding of the natural world, gives the young Aubrey, and by implication the young reader, a way in to understanding what may be affecting their parents’ lives or those of the grown-ups around them. A difficult, and rarely tackled subject for any age, is made accessible and understandable by consciously moving it into a mythical, magical but still natural world through which it can be contained, interrogated and understood.

Works cited

Goudge, Elizabeth (illus. C. Walter Hodges) (1946) A Little White Horse. University of London Press.

Fisher, Catherine (2018) The Clockwork Crow. Cardiff: Firefly Press.

Wynne Jones, Diana (1986) Howl’s Moving Castle. London: Methuen.

Lewis, C.S. (1955) The Magician’s Nephew. London: Bodley Head.

–– (illus. Pauline Baynes) (1950) The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. London: Geoffrey Bles.

Moray Williams, Ursula (1945) The Three Toymakers. London: G.G. Harrap & Co.

Dahl, Roald (illus. Nancy Ekholm Burkert) (1961) James and the Giant Peach. London: Puffin.

Rayner, Shoo (2014) Dragon Gold. Cardiff: Dragonfly.

Claire, Horatio (2016) Aubrey and the Terrible Yoot. Cardiff: Firefly Press.

B.B. (illus. Denys Watkins-Pitchford–the author) (1942) The Little Grey Men. London: Eyre & Spottiswoode.

Hodgson Burnett, Frances (illus. Ethel Franklin Betts) (1905) A Little Princess. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

–– (illus. Charles Robinson) (1911) The Secret Garden. London: Heinemann.