‘All I can do is keep telling stories’ – The remarkable realities of Marcus Sedgwick

This HCAA nominee spotlight is courtesy of Sadia Zafrin Lia and Rowena Seabrook, in partnership with Evelyn Arizpe and the Erasmus Mundus programme, the International Master’s in Children’s Literature, Media and Culture (IMCLMC).

Marcus Sedgwick challenges young readers by depicting darker realities of human existence and instigating their inquisitiveness regarding art, science, and philosophy. As a passionate writer about nature and wildlife, his fictional world shows brutality in human nature, hardship, and social breakdown to create collective consciousness regarding the future of the earth and humanity.

There is something exciting about picking up or downloading a new Marcus Sedgwick, an award-winning British author and illustrator. He has written over 40 books, including novels for young people, with empathy and ambition. Additionally, he plays with form and genre confidently and intelligently, which is unusual in young adult fiction. Sedgwick is a member of Authors 4 Oceans, a collective who are ‘passionate about inspiring children, teachers and parents to love nature and wildlife’ (OUR MISSION, 2018). He is also one of the Climate Fiction Writers League, who believe ‘fiction is one of the best ways to inspire passion, empathy and action in readers’ (Climate Fiction Writers League). Sedgwick’s writing includes The Raven Mysteries; the Elf Girl and Raven Boy series; and graphic novels with his brother, Julian Sedgwick.

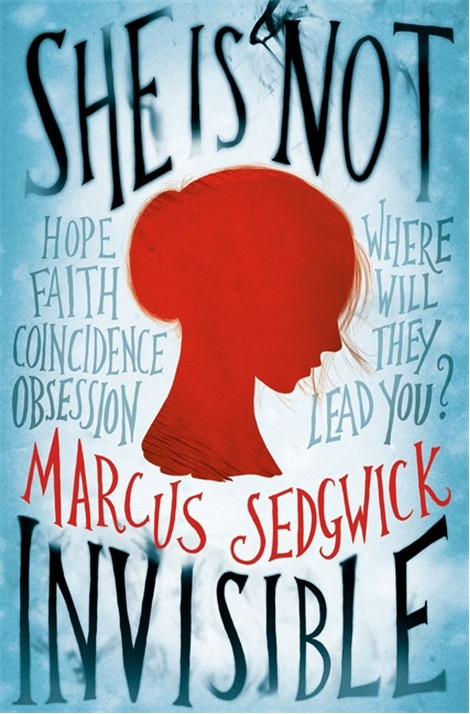

Marcus Sedgwick has been nominated for the Hans Christian Andersen award, 2022. Five of his books are being considered by the panel of judges. These books are Floodland (2000), Revolver (2009), She is Not Invisible (2013), The Ghosts of Heaven (2015) and Saint Death (2016). All of them are published by Hachette UK.

Sedgwick never loses sight of the importance of story. His novels often propel their characters through relentless problems and threats. From the very beginning of the novel Floodland (2000), the reader finds a breathtaking, powerful narrative with the style of a Young Adult thriller. There is a lot of energy and courage portrayed in the protagonist, a teenage girl named Zoe. She thinks and acts more like an adult, adopting survival techniques after being accidentally abandoned by her parents. In her voice, Sedgwick repeatedly mentions the survival of the fittest technique – not to trust anyone. However, Zoe’s life is encircled by two questions: Where are her parents? And why is the sea level rising? Zoe finds the latter answer in William’s muttering, but his voice is ignored by the inhabitants of the Eel’s Island, where Zoe has been imprisoned. For the reader, Zoe’s time is the catastrophic future that the writer pictures as a consequence of global warming. This novel utters a message that when human beings are separated from nature’s blessing their Superego and Ego also leave their company and eventually, they are left with their Id. Sedgwick’s depiction of hardship and societal breakdown seems to be the result of concern for our collective future. In Floodland (2000), William, the only adult person on Eel’s Island, once mentioned that one way of survival is to build a really “big boat.” This may remind the readers of Noah’s Ark from the Bible. The religious connection can be considered as the author foreshadowing Earth’s journey from a dystopia to a utopia which revives everything anew and afresh.

Sedgwick is also a magician of imagery. His language is full of detailed visuals and kinesthetic images that make the story-world more real to the readers. In his unique writing style, keen readers may find his focus on every individual moment, including the thoughts inside the characters’ heads. One good example is the novel Revolver (2009), where death is dealt with through a closer look at a young adult’s psychology. The main character Sig, a fourteen-year-old boy, confronts the death of his father not with grief and despair but also with suspicion and disbelief. Sig also faces an acute existential crisis. When he was eight years old, his father insisted on him confronting the dead body of Reindeer. Six years later, Sig is left alone in a room with his father’s dead body. This gruesome picture may make a young reader a shudder and an adult reader a question about how much horror and realism a Young Adult novel can bear.

Interestingly, this cruel reality taught Sig survival techniques and, like Zoe, he became more mature within a very short period. As in Floodland, Sedgwick’s narrative flows with lots of flashbacks coming from Sig’s memory with his father, Einer. Once he said, ‘A gun is not a weapon. It’s an answer. It’s an answer to the question life throws at you when there’s no one else to help.’ Anyone observing carefully from a philosophical perspective can connect the theory of existentialism, as in many places Sig resembles a young version of Meursault, the protagonist and narrator of Albert Camus’s novella, The Outsider. Moreover, Sedgwick mostly uses “stream of consciousness” as his narrative style, which was largely used by many modern novelists of the twentieth century.

Perhaps Sedgwick is not for every reader because he does not shy away from the darker realities of human existence. Saint Death represents a brutal, unforgiving world on the Mexican-American border. It is heart-breaking and shocking, but Sedgwick’s choices seem driven by a desire for empathy and action in the face of injustice. He is not afraid to challenge his reader intellectually, to invite them into his curiosity about art, science, philosophy and more. Another writer might have become fascinated with the role of the spiral and the helix in all aspects of our history and existence, and written a high-concept science fiction novel. In The Ghosts of Heaven, Sedgwick does write an Arthur C. Clarke-esque story, but sets it alongside three other ‘quarters’ which can be read in any order, with twenty-four possible combinations. One is in verse and tells a story of an early woman and the first art. Another describes the hypocrisy and misogyny that leads to a young woman being accused of witchcraft and then murdered. The last plays with echoes of Lovecraft in a New England asylum where characters grapple with cruelty, mystery, and grief. Each quarter interweaves with the others, stretching across time and space.

It is the combination of ambition and heart which makes Sedgwick’s storytelling so compelling, even – or perhaps, especially – when it makes the reader uncomfortable or unsettled. As he writes, ‘All I can do is go on telling stories, as honestly as I can, even if they run the risk of frightening the children. Some people may not like that, but personally I’d rather let the children decide’ . He is an extraordinary writer and well deserves the nomination for the Hans Christian Andersen Award.

References

Climate Fiction Writers League. (s. d.). Climate Fiction Writers League. https://climate-fiction.org/

Marcus Sedgwick. (2019, juillet 16). Don’t frighten the children. Undiagnosis. https://marcussedgwick.me/2019/07/16/dont-frighten-the-children/

OUR MISSION. (2018). Authors4Oceans. https://www.authors4oceans.org/our-mission-1