From a Mountain to a Rocket: Diversity and Family Representation in Children’s Books in the UK

Patrice Lawrence

My parents met as student nurses in Sussex. They were young and came from different parts of the Caribbean. They were together briefly and split up before I was born.

For me, families have always come in myriad shapes. I have lived in a white foster family, with my unmarried single mother, and with my mother and Italian stepfather before, during and after their marriage. (They got on better after their divorce.) I have never lived in a family where we are all the same colour and never with my biological father.

I was encouraged to read widely from an early age by both my foster mother and my mother. As a black child growing up in a very white society, it never occurred to me that children that looked like me could ever be seen between the pages of a book. However, stories presented me with families that were not the standard nuclear ideal. Dead mothers abounded, not only in classic fairy tales such as ‘Cinderella’ and ‘Sleeping Beauty’, but also in books considered classics such as Heidi and The Secret Garden. The plots of these books are powered by orphaned girls who are sent to live with an extended family member – an angry grandfather and a grieving uncle respectively. I knew that one of my mother’s options for me as a baby was to send me to live with one of her older sisters in Trinidad to be cared for until her nurse training was complete. It is perhaps why I found Heidi and Mary Lennox such absorbing company.

As well as encouraging me to read these books, my mother was a big fan of Anne of Green Gables. Anne is also orphaned, but mistakenly sent to middle-aged siblings, Matthew and Marilla Cuthbert, who wanted to adopt a boy to help them work the farm. As the first of my family to be born in the UK, British but often not considered so, I empathised with the feeling of not belonging. Two other favourites of my mother were Little Women and The Railway Children, both tales featuring single – albeit respectably married – mothers caring for their children while their husbands are absent.

As I look back now, I realise that these books were written and published during the period sometimes referred to as the New Imperialism. The Berlin Conference of 1884–1885 led to the infamous Scramble for Africa, when European countries planned the division, colonisation and exploitation of the African continent. In Beyond the Secret Garden, an article for the children’s literature magazine Books For Keeps, Chetty and Sands-O’Connor note:

British children’s literature rose and gained prominence along with the rise of the British Empire . . . [and] therefore found its way onto bookshelves throughout the world. (2018)

How do the experiences of black and other minority ethnic children write themselves into this national story? One column focusing specifically on classic literature, addresses controversy surrounding the Barnes and Noble ‘Diversity Editions’ of classic texts such as Alice in Wonderland and The Secret Garden, repackaged for US Black History Month with covers depicting main characters as children of colour.

The backlash against taking classic texts, many of which are inherently tied to white European and American ideas of colonization, westward expansion and imperialism, and ‘colouring in’ the main characters to sell more books, was instantaneous and angry. (Chetty and Sands-O’Connor, 2020)

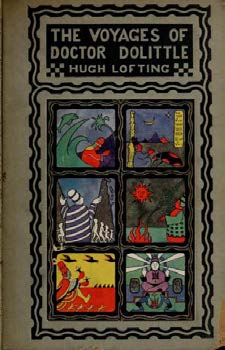

Chetty and Sands-O’Connor also refer to a book with particularly damaging depictions of family. The families that I saw in books as a child were white families. I grew up surrounded by white families. The families on TV and in films were primarily white. The only time I saw – and it was vividly illustrated by the author too – a black family in a book, was in Hugh Lofting’s The Story of Doctor Doolittle. It is a royal family, the King of the Jolliginki (a fictional African country), his wife, Queen Ermintrude, and their son, Prince Bumpo. They live in a palace made of mud and their body and racial features are racist caricatures. Prince Bumpo is stupid and uneducated, in spite of attending university in England. He is persuaded to bleach his skin white if he hopes to marry a princess. I read this book when I was six.

In 2019 the literacy charity Booktrust launched Booktrust Represents, an initiative to increase the number of UK-based children’s writers and illustrators from black and other minority ethnic backgrounds. Booktrust commissioned research to underpin the work. In her introduction to the findings, Ramdarshand Bold reminds us:

Inclusive children’s literature is vital. Children’s books can act as mirrors, to reflect the readers’ own lives, but also as windows so readers can learn about, understand and appreciate the lives of others. They can shape how young readers from minority backgrounds see themselves . . .. (Ramdarshand Bold, p.6)

Furthermore, she reminds us of the warning from the African-American academic, Rudine Sims Bishop:

[W]hen children cannot find themselves reflected in the books they read, or when the images they see are distorted, negative, or laughable, they learn a powerful lesson about how they are devalued in the society of which they are a part. (Ramdarshand Bold, p.17)

I read many of the books referred to above in the 1970s when racism in the UK was embedded within our popular culture. For instance, the popular TV show The Black and White Minstrel Show – white men in blackface singing and dancing with white women – only ended its 20-year run on BBC TV in 1978. The white ‘comedian’, Jim Davidson, appeared on family TV shows imitating a Caribbean accent, the joke being a black character called Chalky. A golliwog adorned the label of the popular Robinson’s jam jars. All the above were used in the repertoire of racist ‘teasing’ by some of my peers at school, and – not infrequently – from adults too. Where were the alternative representations that could challenge those versions of me and my family that were constantly reflected back at me?

I never found them.

When I became a mother myself in the mid-1990s, I was acutely aware of the lack of children’s books with positive representation of black mothers. I was also acutely aware of the many stereotypes of black motherhood, especially single black motherhood when I found myself in that situation a few years later. Finally, as a mother of a mixed heritage child with a lighter skin shade than mine, I knew that our family would – and did indeed – evoke curious questions. I did not have the luxury to wait to discuss ‘race’ and racism with my child. I saw it as essential to my parenting role from the beginning to reinforce a positive view of black and mixed heritage families. Books were essential to this.

Of course, many picture books for young children depict animal families. Yes, the Nutbrown Hares in Guess how much I Love You are irresistible. We were also big fans of Lauren Child’s Charlie and Lola series. The relationship between the older brother and his mischievous sister felt beautifully realised and hummed with kindness and love. But where were the stories with a child of colour and their family at the centre, just like the many, many white children we had read about?

Our first find was Tickle Tickle, written by Dakari Hru and illustrated by Ken Wilson-Max. A darker-skinned father is playing with his lighter-skinned baby. The text is rhythmic and repeated like a song. The images are large and vivid. The loving relationship between the baby and father is unquestionable. Our favourite book, however, was So Much, written by Trish Cooke and illustrated by Helen Oxenbury. Although I did not grow up surrounded by my Caribbean family, I recognised the characters instantly. Uncle Didi’s fade, Mum’s braids, Aunty Bibba’s desert boots, Nannie and Gran-Gran’s handbags are all also a snapshot of 1990s UK Caribbean fashion! Most important of all was the father figure. He is wearing a suit – something that felt so significant to me. He works in an office or even a bank. Perhaps he’s even in charge. This representation was counter to so many of the negative stereotypes that abound about black men and fathers. The father arrives home a little grumpy, but is soon surrounded by the loving energy of the family gathered for his surprise party.

And then, finally, I found a book with a mixed heritage family. It was Wait and See, written by Tony Bradman and illustrated by Eileen Browne. Jo’s mother is black and her father white, and, like my daughter’s father, enjoys a spot of baking! I learned later that it’s set in Finsbury Park in north London just up the road from where we lived in east London. This was why the shops and community it depicted felt very familiar. But why, in the twenty-first century, was it so difficult to find a book with an explicitly mixed heritage family in a high-street bookshop? It feels even more bizarre when the UK censuses in 2001 and 2011 showed that ‘mixed race’ people were the fasting growing ethnic category – and one of the youngest.

It is now 2020. There has definitely been an improvement in the diversity of families in children’s books. Spacegirl Pukes (written by Katy Wilson and illustrated by Vanda Carter) was originally published in 2005 then reprinted and relaunched in 2017. As well as neon-bright vomit, there is a young astronaut with her two mothers, Mummy Loula and Mummy Neenee, who are different colours. Mixed heritage Luna in Luna Loves Library Day (written by Joseph Coelho and illustrated by Fiona Lumbers) also has parents that are different colours, but they are separated. Luna spends a day with her black father exploring the imaginative worlds contained in library books.

Another book written by Joseph Coelho, illustrated by Allison Colpoys, reminds us that mixed heritage families are not just black and white. If all the World Were . . . is a poetic, sensitive depiction of loss and stories, and the relationship between a granddaughter and her grandfather – ‘If all the world were memories/the past would be rooms I could visit/ and in each room would be my granddad.’ The text is on a page illustrated with the grandfather holding his granddaughter against a backdrop of a wall filled with photos of the multi-ethnic family. A few pages along, the granddad is no longer there, just his empty chair, slippers and glasses . . ..

Finally, we return to space – or nearly – with Rocket in Look Up!, written by Nathan Bryon and illustrated by Dapo Adeola. This is a book about Rocket, a space-obsessed little black girl who wants to be an astronaut. She is passionate about a once in a lifetime opportunity to see a comet, but her phone-obsessed older brother Jamal is less interested. For me, the glory is in the illustrations. These are the pictures that I needed when I was a child, that would have made me feel valued and capable of changing the world. Having seen the many pictures Adeola posted of black children dressing up as Rocket on World Book Day, many parents and carers feel the same way. At last, this is a hero for their children. In these divided times, my hope is for many more books that celebrate the rich variation of family life both as a mirror and as a window for us to look through, enjoy and learn.

Works cited

Alcott, Louisa May (1868–1869) Little Women. Boston, MA: Roberts Brothers.

Bradman, Tony (illus. Eileen Browne) (1988) Wait and See. London: Frances Lincoln Children’s Books.

Bryon, Nathan (illus. Dapo Adeola) (2019) Look Up!. London: Puffin.

Chetty, Darren and Karen Sands-O’Connor (2018) Beyond the Secret Garden? Part One: The Fantasy of Story. Books for Keeps, no. 228.

http://booksforkeeps.co.uk/issue/228/childrens-books/articles/beyond-the-secret-garden-part-one-the-fantasy-of-story.

–– (2020) Beyond the Secret Garden: Classic Literature and Classic Mistakes. Books for Keeps, no. 241. http://booksforkeeps.co.uk/issue/241/childrens-books/articles/beyond-the-secret-garden-classic-literature-and-classic-mistakes.

Child, Lauren (2000–2010) Original Charlie and Lola series. London: Orchard Books.

Coelho, Joseph (illus. Allison Colpoys) (2018) If all the World Were . . .. London: Frances Lincoln Children’s Books.

Coelho, Joseph (illus. Fiona Lumbers) (2017) Luna Loves Library Day. London: Andersen Press.

Cooke, Trish (illus. Helen Oxenbury) (1994) So Much. London: Walker.

Hodgson Burnett, Frances (1911) The Secret Garden. London: William Heinemann.

Hru, Dakari (illus. Ken Wilson-Max) (2004) Tickle Tickle. London: Bloomsbury.

Lofting, Hugh (1924) (illus. by the author) The Story of Doctor Dolittle. London: Cape.

McBratney, Sam (illus. Anita Jeram) (1994) Guess how much I Love You. London: Walker.

Montgomery, L.M. (1908) Anne of Green Gables. Boston, MA: Page & Co.

Nesbit, E. (1906) The Railway Children. London: Wells, Gardner, Darton.

Ramdarshand Bold, Melanie (2010) Representation of People of Colour among Children’s Book Authors and Illustrators. Booktrust.

https://www.booktrust.org.uk/globalassets/resources/represents/booktrust-represents-diversity-childrens-authors-illustrators-report.pdf.

Spyri, Johanna (1880 and 1882) Heidi. Gotha, Thuringia, Germany: F.A. Perthes. (First English translation (1882) Heidi’s Early Experiences/ Heidi’s Further Experiences. London: W. Swan Sonnenschein.)

Wilson, Katy (illus. Vanda Carter) (2005/2017). Spacegirl Pukes. London: Onlywomen Press/Spacegirl Books Ltd.

Patrice Lawrence is an award-winning British writer of books for children and young people. She has worked with the UK charity Booktrust on increasing the ethnic diversity of children’s writers and illustrators. Patrice Lawrence has worked in the UK charity sector for over 20 years on projects and policy initiatives promoting social justice, anti-discrimination and elevating the voices of marginalised communities.