The Emma Press

The Emma Press publishes beautifully designed collections of poetry and prose for adults and children from otherwise unheard voices, including children’s poetry from Indonesia, Estonia, Latvia and Spain.

In this interview we speak to founder and IBBY supporter Emma Dai’an Wright about being an unconventional voice in the publishing industry, the attraction of working with translated literature and how the Emma Press is helping to update the definition of poetry for children.

What made you decide to set up The Emma Press?

Not long after graduating I ended up working in publishing, doing e-book admin and production at Orion Books. I was there for 2 years and I started thinking a lot about who was deciding what got published, about book design and publicity and how I’d make books myself. I started feeling frustrated about how hard it is for people in the lower rungs of publishing to progress. So, I left in 2012 and put all of that thinking into The Emma Press.

So it was very much a personal project for you?

Yes. I thought: this is going to be my thing. I decide how it works. I’ll do everything and just the fact that I’m doing it is something of value. Because there weren’t enough people like me running publishers and being gatekeepers. It was something for me – that’s why it’s The Emma Press. As well as being about making things that are beautiful, through and through.

What is an Emma book? How do you decide what to publish?

I’m trying to publish things that I like and that have value in themselves. Whether it’s a poem or a concept for an anthology, it’s something that speaks to me. As a young British Asian woman who isn’t a poet I’m aware that my perspective isn’t the prevalent one in publishing. I’m very conscious that my reaction to texts isn’t necessarily going to be shared by a lot of people. But that’s hopefully what I’m bringing to the publishing industry and the readers. I’m picking out something that won’t necessarily speak to everyone, and that’s fine.

Have you been publishing children’s books since the beginning?

No. It’s always been something I wanted to do but I guess I was adding in things as I felt comfortable with each one. I started with poetry for adults and did that for a couple of years, and then I added in the first children’s poetry anthology. The children’s list has been growing very slowly. At the moment about a 3rd of our titles are books for children and I’m aiming for it to be half and half. In the children’s book world our press is tiny and I’ve got a lot of work to do. But I love children’s books! I’d really like The Emma Press to be known for children’s books as well as for poetry and short form prose.

You started publishing translated works in 2017. How much did you know about the translation process before you started?

I have translation in my background as I studied Classics at university. I think that has been really useful. It means I’ve thought a lot about how you approach translations: you can go very far away or you can stick very closely to it and then it reads very robotically. I really enjoy editing translations as well. I try to respect the original work and the translator’s work but also try to respect the reader’s experience and bring that together.

How do you work with the translators?

I prioritise my experience as an editor of poetry. I look at the text and see if there’s anything that jumps out at me and then I query it with the translator. Or if their phrasing makes it seem like a translation then I also query that. I enjoy the fact that you don’t have to shape a translated poem in any way. It’s liberating to think that the poem already exists in the original language and all I have to do is the tidying. I quite like that tidying process.

What attracted you to publishing international children’s poetry?

I felt like the sort of poetry being published in the UK for children was quite limited. I was really interested to see what else was being published around the world. I had a hunch that it was going to be a lot more varied and exciting. There also wasn’t that much poetry being published in the UK for children so I wanted to add some more to the mix to broaden it out. Who knows if it will pay off – maybe no one’s reading them! But it’s now possible to read more poetry for children and to see what’s being published in a few countries. Hopefully I can build a little library of children’s poetry books from other countries and that will inspire more people to write in a different way.

What would you say is the main difference between UK children’s poetry and international children’s poetry?

From what I’ve seen, outside of the UK there’s a broader definition of what poetry for children is. In the UK there are some poets writing in a really interesting, thoughtful way, but I think a big section of poetry for children is quite one level and jokey. The quality isn’t that high. I think poetry for children should stand up against the standards that you judge adult poetry by. The poetry I’ve seen from outside of the UK has a wider range of tones and concepts. There’s a book I’m hoping to acquire by Guatemalan author Julio Serrano Echeverria, set in a block of flats. It’s about the different people who live there, which is just really interesting.

You’ve published books from Latvia, Estonia, Spain and Indonesia. Why did you choose those particular countries?

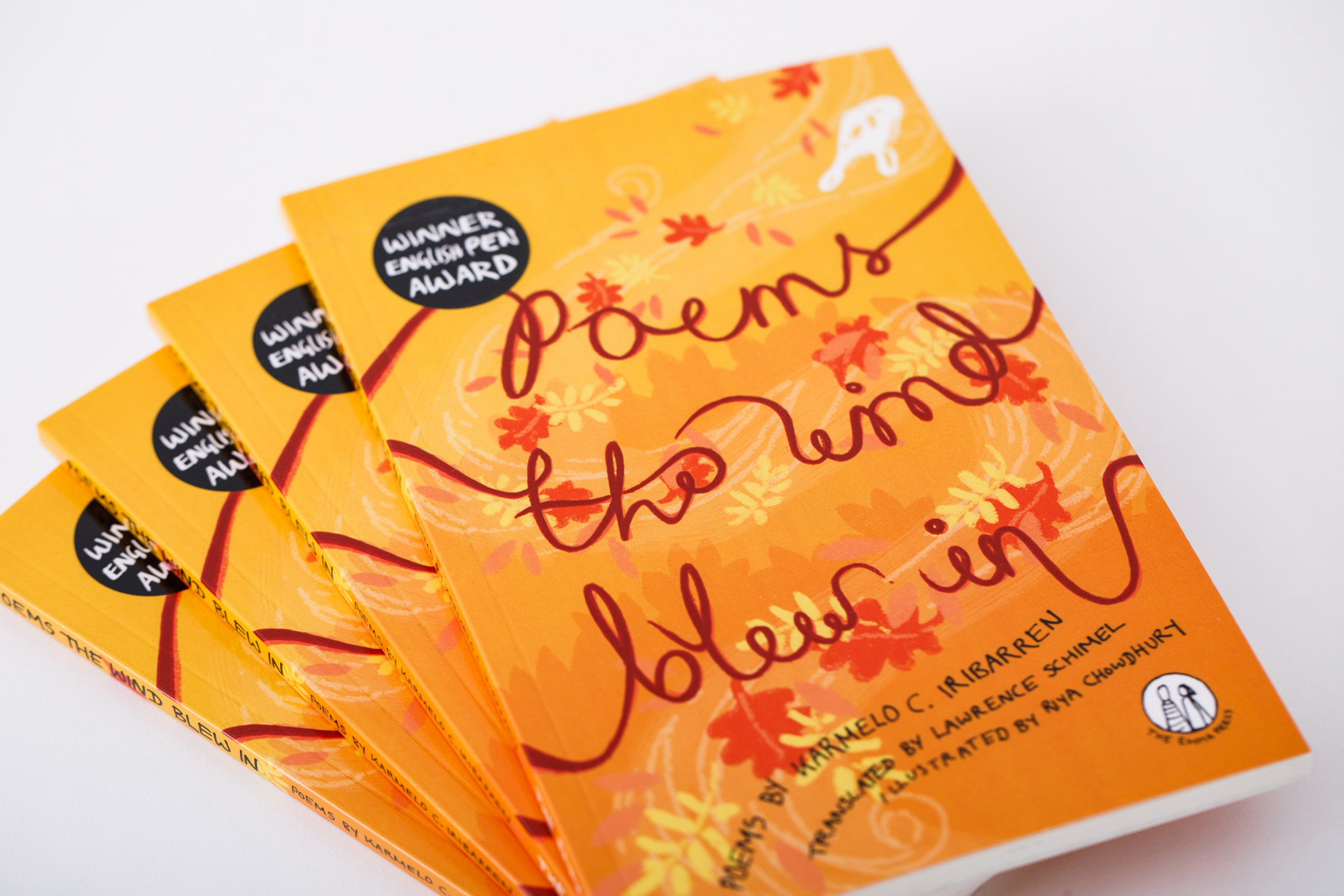

It was partly just connections. Lawrence Schimmel [co-founder of World Kid Lit] recommended a Spanish children’s poetry collection to me, Poems the Wind Blew in, and he recommended a translator from Dutch, David Colmer, who pitched Super Guppy to me. Then the British Council were showcasing the Baltic countries at the London Book Fair so I ended up publishing a Latvian children’s poetry collection and then an Estonian poetry collection. The year after that was the Indonesian focus and that’s how I ended up acquiring the rights to a few children’s books from Indonesia. But then I decided it was exhausting chasing the British Council focuses, so I stopped!

Was it easy to find collections of children’s poetry to translate to English?

No. A lot of countries aren’t foregrounding their poetry because there isn’t much of a demand for children’s poetry in England. With the Estonian one, there was only 1 children’s poetry book in their whole catalogue. Most publishers wouldn’t have bothered putting space aside in their catalogue for poetry. I did a lot of work trying to find them.

Is there one book in particular that you’ve published that you’re really proud of and you’d like it to get a bit more attention?

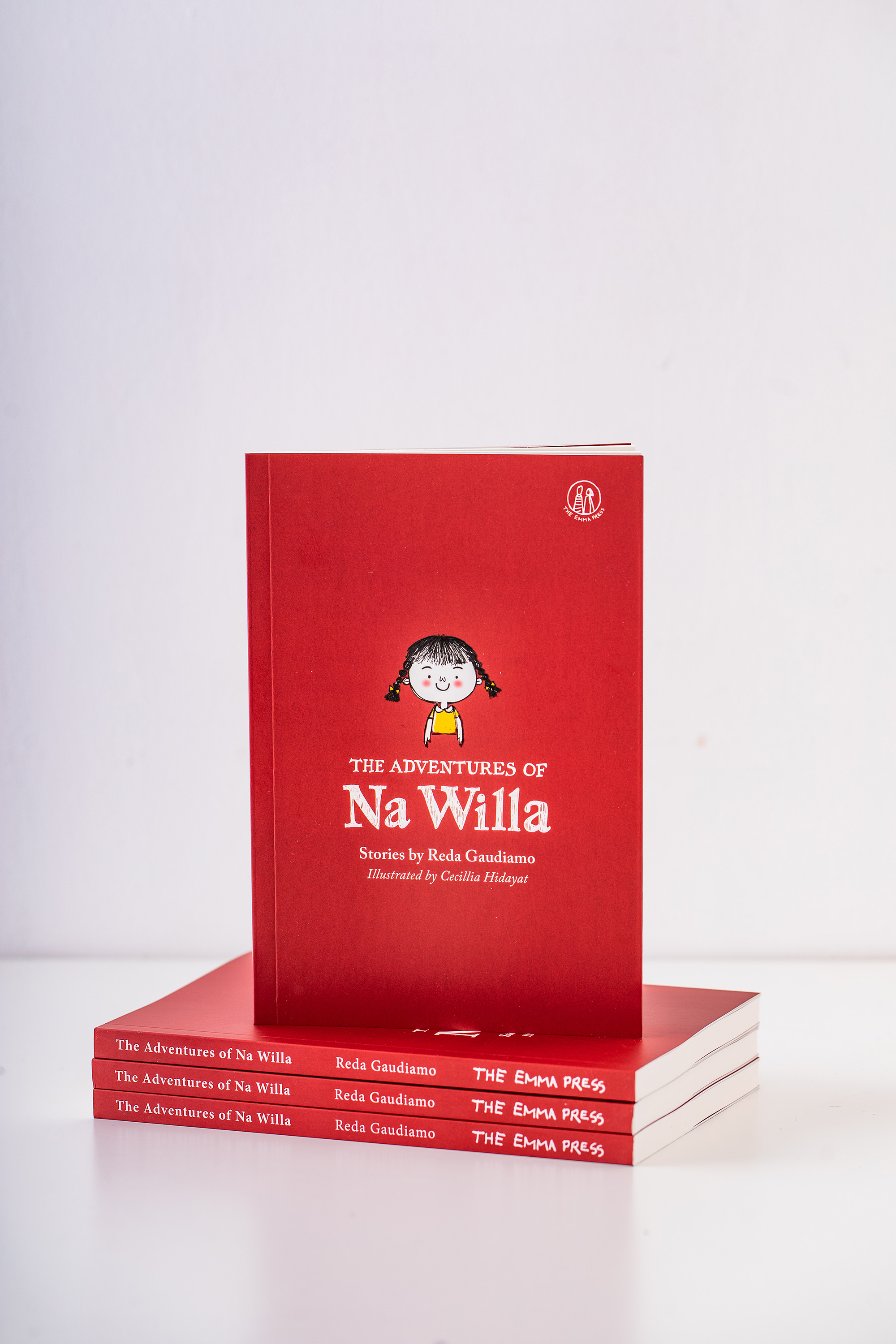

I’d always like more spotlight for The Adventures of Na Willa by Reda Gaudiamo, translated by Ikhda Ayuning Maharsi Degoul and Kate Wakeling. I just love it so much! I feel like it could be a classic. It’s set in Indonesia in the 1950s and it’s about a girl with mixed heritage. Her mother is from East Indonesia and her dad is Chinese-Indonesian. She experiences a lot of things but it’s told in a really gentle way, so children would notice on an instinctive level that the little girl is being made to feel uncomfortable and as an adult you think, ‘Oh, that’s what’s going on and that’s not very nice’. It’s very beautifully done. It’s capturing the author’s childhood and memories, but it also makes a case for inclusivity and a varied multicultural society.

On your website you talk about the importance of increasing the representation of unheard voices in publishing. How would you say this applies to the international children’s literature you publish?

I think just publishing books in translation is a really powerful thing. There’s a sense that most people are just British but actually a lot of people feel connected to lots of different countries and I think everyone’s richer for it when we acknowledge that. Sometimes you don’t feel entirely from the place where you’re living in or you have a connection with another country. I think translation has the very important role of normalising it and saying, “Yes, we’re not homogenous.” Translations add to the sense that we’re all global people.

Have you had any feedback from your child readers?

Only little bits. Books for Keeps had a review where a class was reading poetry books, including The Noisy Classroom [translated from Latvian] and there were some really cute reviews from these Years 2s. There was one girl who said, ‘I can’t speak Latvian so I am happy these poems have been translated otherwise I wouldn’t have known about them. My first languages are Greek and Albanian so I know how important it is to be able to translate good writing into a language people can understand.’ I thought that was really sweet! My first language isn’t English either and I relate to her enjoying the international aspect of the book. World Kid Lit helped me champion The Adventures of Na Willa too, and they posted a review by 7-year-old Juliet that said, ‘It’s really hard to describe all of the things we liked about this book. It was funny, sometimes a little sad, and very descriptive.’ Job done!

What language did you speak at home?

I spoke Hubei, which is a dialect of Mandarin from the Hubei province of China, to my mum, and English to my dad, though he understood the Hubei as he’s a Mandarin teacher.

Would you be interested in publishing Chinese books?

Yes, but I’m also drawn to very small publishers. It’s about finding the equivalents of The Emma Press around the world. Normally it’s 1 or 2 women running a little press, and that really couldn’t exist in China as there’s no independent press scene. The Emma Press wouldn’t exist there because it’s not allowed. My mum is from a Chinese family in Vietnam so I’d like to publish books from Vietnam. That’s why I do a lot of mixed things, because my background is quite complex. There is some freedom in Vietnam, which makes me think I probably could find a publisher there who I liked. I just have to do the research.

Do you have any help at the press?

I had been on my own for the last 9 years but I got Arts Council funding at the start of last year. That made the pandemic a lot less scary as otherwise I would have been terrified about just staying afloat. I got one new staff member, Pema, who is our Ecommerce Executive. She’s working on driving the direct sales, and that’s a really important part of the business. And I’m in the process of hiring a publishing assistant, so there will be 3 of us. Hopefully in the next 2 or 3 months I’ll be able to look a bit further ahead rather than just day by day.

What are you working on at the moment?

We’re starting with making our packaging nicer. So far we just package the books in a paper bag and we’re trying to make that a nicer experience. We’ve just created a little zine with some poems so people can cut that out and stick it on their walls. I think it’s important for people to realise that it’s humans making the things that they’re getting. It’s easy to distance yourself from that, but everything you get from The Emma Press is something I’ve worked on and Pema’s worked on and our local printer Joseph has printed and folded them. So many actual hands have gone into making these things. The reason why it’s called The Emma Press is to remind people that a lot of care has gone into it. Hopefully it’s heartening to know that there are people out there working away in the background to bring beautiful things into the world.

What are your ultimate hopes for The Emma Press?

Hopefully The Emma Press will be something that chimes with people. Obviously it isn’t for everyone but for some people maybe it will represent something that doesn’t exist elsewhere. Something they feel really comfortable and happy with. It’s nice to be able to do that!

Thanks for talking to us today Emma and good luck with your new team and future projects! Discover more about The Emma Press and sign up to their newsletters.