Down to the Sea in a Homemade Boat

Nicholas Tucker

‘Boys who love boats will delight in making this serviceable canoe. It is 12 foot long 2 foot 9 wide. It can be used safely on any smooth water.’

So E.W. Hobbs, writes in The Boy’s Own Book of Pets and Hobbies (1912). He was advising on how to construct at home ‘a simple canvas canoe’. The very detailed instructions and diagrams that follow are anything but simple, yet clearly seen as no obstacle to what is elsewhere described as ‘the soaring human boy’.

Apart from a casual remark about avoiding ‘ocean voyages’, there is only one other mention of hazards facing those completing this task and then wanting to put it to the test.

Do not canoe unless you can swim. A canoeist, particularly when racing, thinks nothing of an upset, which to an accomplished hand is merely the loss of a few minutes when, the canoe righted and the owner once more in charge, the prize is still held in view. This, to a non-swimmer, might mean, however, loss of life. Speaking from my own experience, I can assure you that I should not now be writing this if I had been unable to swim, and in no case should canoeing or boating be indulged in by those who have not mastered this necessary and simple art. (pp.337–8)

Sensible advice indeed, albeit delivered as if ‘loss of life’ was just one of those tiresome possibilities that crop up from time to time. But even moderately proficient young swimmers surely need more warnings about the sea at its most unforgiving.

Here too some years later is Geoffrey Prout, editor and contributor to Canoes, Dinghies and Sailing Punts (1934). Writing on ‘How to build a sailing “box”’, he opines:

Theoretically, if within swimming distance of the shore, you are as safe as houses. But currents often set strongly offshore; offshore winds might blow one out. There are a hundred and one things which would prove dangerous to an inexperienced sailor of a sneak box. So don’t try any channel crossing if you build a sneak box for yourself! (p.91)

But these authors are addressing boys, not men, with an opening advertisement for Bassetts Allsorts – ‘the finest sweets you can spend your pocket money on’ – setting the tone for what follows. In 1938 there were 590 male deaths by accidental drowning in the UK. Could some of these have involved over-confident but under-prepared children, failing to take what little safety advice they might (or might not) have been given?

Eight years earlier saw the publication of Arthur Ransome’s first sailing adventure story, Swallows and Amazons. In this a family of children, the youngest of whom is seven, take to the water for an extended trip on their own without any safety jackets. Parental assent is provided by their father, absent on naval duties himself, who, when asked by his wife whether she should allow such adventures, cables back ‘BETTER DROWNED THAN DUFFERS. IF NOT DUFFERS WON’T DROWN’. ‘Hurrah for Daddy!’ shouts John, the oldest, on hearing this news. But this would have made uncomfortable reading in a coroner’s court had the worst actually happened, always a possibility in real life when lakeside sailing at night with only lanterns for guidance.

Ransome’s story was well received by a young audience with parents able to afford hardback novels. Some of these readers may already have sailed themselves. For the rest, as Malcolm Muggeridge pointed out in a review in 1930, ‘The book is the very stuff of play. It is make-believe such as all children have indulged in; even children who have not been so fortunate as to have a lake and a boat and an island but only a backyard amongst the semis of Suburbia’.

This typically shrewd point is not one that Ransome would have recognised. A keen amateur sailor himself, his book was based on genuine adventures enjoyed on Lake Coniston with children he had befriended from the neighbouring Altounyan family. Swallows and Amazons was initially dedicated to them. But even he seems at a later stage to have had some second thoughts about possible safety implications. In We Didn’t Mean to Go to Sea, published in 1937, the same children are now found alone on a borrowed sailing cutter. After a night storm where they lose their anchor they are swept out into the ocean from their berth on the mouth of the river Orwell. Captain John uncharacteristically weeps with relief as his father finally comes to the rescue after his children survive a perilous journey in the fog before ending up in a harbour on the Dutch coast. The underlying advice here is clear: there is only so much immature sailors can manage before the elements at their worst become too much for them.

This story had a particular meaning for me, given that when very young there was a moment when I too didn’t mean to go to sea. In 1940 my parents moved into Lane Head, a large house once owned by Ruskin’s secretary William Collingwood. Situated on the edge of Coniston Water, it had a fine view of the mountain opposite, always known as Coniston Old Man. It was now owned by a prominent local Quaker who ran it as a commune for kindred souls escaping the blitz. The children’s novelist Diana Wynne Jones and her parents were also there, along with other couples, one of whom preferred talking in German because they found the language ‘more spiritual’.

I remember my father paddling out in a canoe to rescue me, shouting out not to stand up until he got there.

But while all these high-minded adults were indoors debating pacifism or whatever, as well as quarrelling among themselves, their children, who ate at separate tables and shared a communal clothes basket, were largely left to run wild. A boathouse bordering the lake was the focus for most of our games. One day my older brother, aged six, thought it would be fun to launch me, aged three, into the lake sitting on a wooden raft. Eventually my parents were called, and I remember my father paddling out in a canoe to rescue me, shouting out not to stand up until he got there. After that, Arthur Ransome’s stories of super-competent child sailors equal to nearly all challenges never appealed to me. My brother, to be fair, rescued another child a week later from possible drowning. Arthur Ransome himself, who lived nearby, only visited Lane Head once, in order to complain about the noise we were all making while he was trying to write – about high-spirited children who in real life would probably have been making quite a lot of noise themselves.

There is no direct link between the benign neglect our parents at the time showed towards the dangers of letting children play unsupervised on a lake and reading any of Arthur Ransome’s novels. But the rose-tinted fantasy element in his and other adventure stories fed into a culture that habitually minimised dangers rather than warned children – and their parents – about what might happen if things went wrong. The same could be said of the maritime hobby suggestions found in back pages of The Boy’s Own Paper at the same time.

Some readers might well have turned away from such displays of rampant enthusiasm, all too conscious of their own inadequacy as one supremely taxing suggestion follows another. But others, even with no intention of undertaking such tasks for themselves, could still enjoy the idea that they might, just as many adult readers enjoy perusing cookery books without ever getting round to trying out the recipes. Even in fantasy, it could still be nice to be assured by Geoffrey Prout that ‘Every boy who likes paddling a canoe, or sailing a boat on river or lake, much prefers to make his own craft if circumstances allow’. Building a ‘Canadian cruising bateau’, he goes on, is ‘Simplicity itself, with costs running at under 25 shillings’. (1939: 112)

And not just homemade boats: there is also a piece in The Boy’s Own Paper, quoted in Karl Sabbagh’s amusing study Your Case is Hopeless: Bracing Advice from The Boy’s Own Paper (2007) on ‘How to make an Astronomical Telescope’ (p.252). Another contemporary edition of The Boy’s Own Paper has the editor telling a correspondent that ‘We are indeed glad to hear that you have succeeded in making a very fair and good-toned violin from our articles, as we must confess that it is by no means an easy thing to do. Violin-making requires much patience and ingenuity’ (Sabbagh, p.249)

So yes, there always were a few readers then who did manage to construct some of the fiendishly difficult boats and other articles so resoundingly recommended to children over the years. It could also be that the pervasive ever-positive spirit in these hobby pages, along with accompanying, mostly heroic, stories, proved useful in 1939 and after.

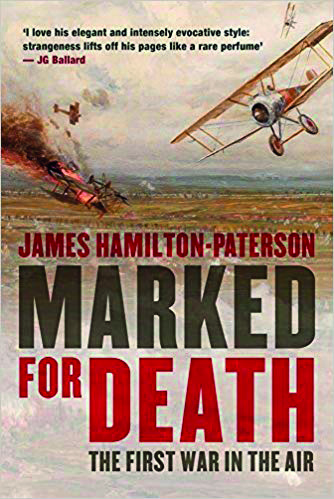

James Hamilton-Paterson’s study Marked for Death (2016), ran interviews with pilots, some of whom in their youth had taken part in the Battle of Britain. Several of these claimed that they had been particularly inspired at the time by having read Captain W.E. Johns’ best-selling fiction featuring that audacious and ever-undaunted fighter-pilot Biggles. As part of the general, largely unquestioning ‘Can-do’ atmosphere so prevalent in writing for older children at the time, could all those highly aspirational if often impractical hobby suggestions found in The Boy’s Own Paper and elsewhere also have had some influence here too?

Works cited

The Boy’s Own Paper (1879–1967). London: Religious Tract Society (1879–1938); Lutterworth Press (1938–1962); Purnell and Sons Ltd. (1963–1964); BPC Publishing Ltd. (1965–1967).

Hamilton-Paterson, James (2016) Marked for Death. Cambridge: Pegasus.

Hobbs, E.W. (1912) How to make a Simple Canvas Canoe. In Morley Adams (ed.) The Boy’s Own Book of Pets and Hobbies. London: Religious Track Society.

Hobbs, E.W. (1938) How to Make a Simple Canvas Canoe. In Jon E. Lewis (ed.) (2008) The Mammoth Books of Boys Own Stuff: A Staggeringly Large Guide to all that a Modern Boy Needs to Know and Do. London: Constable & Robinson Ltd.

Johns, W.E. (1932–1939) Biggles series of books. Various publishers, many by Hodder & Stoughton and Brockhampton Press.

Muggeridge , Malcolm (1930) Swallows and Amazons Book Review. The Manchester Guardian, 30 July 1930.

Prout, Geoffrey (1932) The ‘B.O.P.’ Canadian Cruising Bateau. The Boy’s Own Paper, May 1932.

Prout, Geoffrey (1934) How to Build a Sailing ‘Box’. In Canoes, Dinghies and Sailing Punts. The Boy’s Own Paper Office.

Ransome, Arthur (1930) Swallows and Amazons. London: Jonathan Cape.

Ransome, Arthur (1937) We Didn’t Mean to Go to Sea. London: Jonathan Cape.

Sabbagh, Karl (2007) Your Case is Hopeless: Bracing Advice from The Boy’s Own Paper. London: John Murray.

Nicholas Tucker has written and broadcast on the subject of children’s literature for the last 50 years. He has written a number of books on the subject. His book Darkness Visible: Philip Pullman and his Dark Materials published by Icon Books came out in a new edition in 2017.