Children’s Literature in Lithuania

1. Could you tell us a bit about the publishing scene in Lithuania, especially for young people.

I suppose it is worth mentioning that we are a nation of three million. This helps putting facts and figures about publishing for children and young readers in perspective. I guess you will be surprised to learn that there are nearly 50 publishers working in this line of business. However, some of them publish just a few titles a year or don’t publish anything some years. So the bulk of production comes from three or five publishers. Most of them publish for adults as well, but there is one publishing house that has focused on children’s literature for nearly 15 years and managed to be particularly demanding about the quality of the text and illustrations.

There are new publishers which have plans to focus only on children’s literature. The number of titles and copies varies, depending on the economic situation of the country. Recent years have seen the situation settle down to around 600 titles. Nearly half of them are for the smallest audience, mostly preschool or primary grades. This trend is easy to explain. The books are fairly thin, and young parents feel an obligation to invest in their offspring and are a fairly active customer base. It is disheartening, however, that quite a few of those books are not good. You wouldn’t admire them for their artistic or pedagogic value. Lithuanian writers and artists account for almost 35% of all titles, which include reprints.

We have nearly 100 new books by Lithuanian authors published annually. Some of them are published by amateurs, the remaining come from professional authors. As a country we are big in translations for children. Around 75% of all books are translations from other languages. After 1990, when we regained our independence, we translated many classic books that were not accessible to our readers before. Authors include Alcott, Burnett, Montgomery, Porter, Rowling, Preusler, Krüss and others. These days we have many translations from contemporary authors, particularly for young readers. Some of them are purely commercial publications, but a significant portion of them are books of value. Our publishers started taking an interest in publications that have received Hans Christian Andersen or Astrid Lindgren awards. Newbery or Carnegie medals ring a bell too. Of course, most books are translated from the English language and predominantly come from UK or USA authors. However, Lithuanians have a sweet spot for Scandinavian literature. For many years Astrid Lindgren was and probably still is one of the most popular authors. Overall, it is good to note that recent years have seen the arrival of a new generation of translators who can translate from virtually any language. It is not surprising to have books translated from 20 or 30 languages in some years. I think that the number of titles is fairly substantial for a country the size of Lithuania. The print runs, between 1500–2000 copies, are a different story. It is always sad to see significant classic books published in small numbers.

2. Historical influences. So little is known here about the Baltic States that to learn about the links with Scandinavia, Sweden and Germany that have created a distinctive Estonian voice, and, of course, the Soviet influence, which form part of your heritage, would be very interesting and enlightening.

I suppose I have to remind readers of several historical facts first. Differently from other Baltic countries, the Lithuanian language was banned from Lithuanian public life for nearly 40 years by the Russian tsarist administration in the period from 1864 to 1904. Publishing in Lithuanian was also banned. Lithuania became an independent country in 1918 and remained independent until 1940. These two decades were highly significant and in the middle of 1930s we already had professional children’s literature in place. So the tradition of children’s literature was very young. We also saw the first translations at the same time. After 1920, three significant authors emerged and had their fairy-tale collections published. These were the Grimm brothers, Hans Christian Andersen and Wilhelm Hauff. These books stuck in the memory of the generation of my parents and grandparents. They were reprinted in the twentieth century. Recent years also saw new translations of these classic fairy tales. I may be subjective, but my guess is that it was due to the influence of these authors that the genre of the literary fairy tale has been so prolific for a long time, irrespective of the fact that Mark Twain, Carlo Collodi, Edmondo de Amici, Jules Verne, Harriet Beecher Stowe and other classic authors had been translated during the same decade.

For 50 years Lithuania had been annexed by the Soviet Union. It is a very long period of time. Soviet propagandists controlled all Lithuanian culture. Effectively, all the translations were done only from the Russian language. Books by the so-called Western authors could only be published after prior publication and approval by Moscow. The amount of Soviet propaganda in children’s books published between 1945 and 1955 is staggering. Later on, however, our authors managed to acquire a certain level of independence. Quite a few books from that period have become classics. The period from 1963 to 1969 was particularly fruitful. At that time our literature was still aiming at developing norms of morality in children, but did so in a playful and amusing way, closely mimicking the psychology of children. However, the Soviet oppression gave rise to an unexpected phenomenon – a range of allegorical and philosophical literary fairy tales. Some children’s books published in the period between 1975 and 1985 used Aesop’s language to deliver quite a few politically ‘dangerous’ messages. Dangerous to such an extent, that they were never referred to in the mainstreamliterature.

3. Reading promotion activities. How do you reach your markets, reading challenges/initiatives, booklists, book fairs, school provision, public libraries? I understand you have a wonderful cultural institution – we should love to hear about it.

Quite a few book promotion activities come from IBBY Lithuania. We aim to educate adults so that they are better at knowing what valuable children’s literature is. Another aim is to make sure that our teenagers get their hands on as good literature as possible. We actively celebrate International Children’s Book Day. On this day IBBY Lithuania makes nine awards to children’s writers, illustrators and researchers. We also have a tradition of inviting children to a theatre on that day and together watch a play based on a literary work for children. It costs nothing to them. It is also important that there are quite a few events and festivals in local schools and libraries. There are some 2500 libraries in Lithuania and nearly all of them have a children’s literature section. Nearly every school has a library.

We have had the Most Significant Book of the Year Award for ten years now, where votes are given for the latest books by Lithuanian authors. Alongside the best book for adults, Children’s Book of the Year and Young Adult Book of the Year have their spots too. The commission usually comprises IBBY members, a shortlist of five books and finally readers cast their votes for the one book that they like most. This campaign results in a great deal of activity in libraries. Children are actively involved in the whole process. Recent years have also seen teenager involvement grow because of the increase in titles focused on the needs of this particular group of readers.

Libraries regularly host reading-aloud events, followed by some creative activities; the week of Nordic libraries takes place annually, there are book clubs and so on. Children also have websites where they can find information on the latest books, share their impressions and creative endeavours with their peers; the most active readers may win prizes. Public organisations are actively cooperating with the national broadcasting service, which regularly runs reading promotion campaigns on TV.

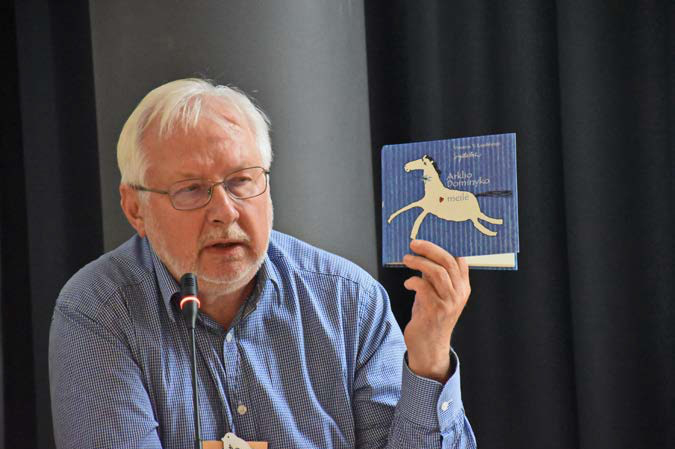

It’s good that you asked about book fairs. Every February Vilnius hosts an international book fair, which is very popular. It is not only a place to buy books. Young readers have a dedicated space where they can draw, create books and meet with writers and illustrators. Foreign authors also visit the fair every year.

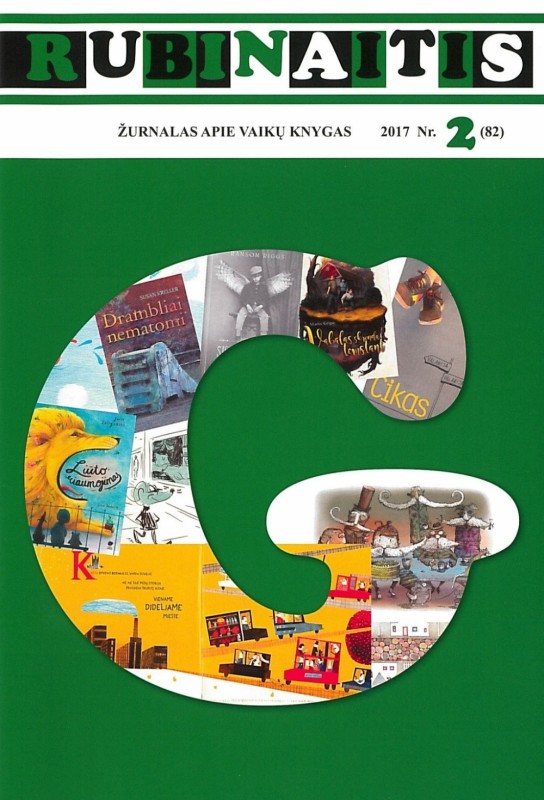

Rubinaitis, a quarterly Bookbird equivalent, is a handy resource for teachers, librarians and parents who want to know more about good literature for children and young readers. As far as I know, it is the only publication of this kind in the post-Sovietbloc.

The success of IBBY Lithuania hinges on the fact that we have fought our way to recognition and are now supported by the Lithuania government. It is also very important that we work hand in hand with the National Library of Lithuania.

I’ve just mentioned Rubinaitis, which we are really proud about. We are also proud about 100 Books for Children and Lithuania, our project that marks the centenary of independence of our country. We composed a list of 500 books and asked adults readers from all walks of life to vote. The resulting list and a list comprised by experts then formed the ultimate list. We currently have a booklet called 100 Most Significant Lithuanian Books for Children. I am referring to this project because it helps to cast light on the specificities of Lithuanian children’s literature. It is truly amazing to see as many as 30 books of poetry in the top 100. Lithuania has very old and strong traditions of poetry for children and adult readers alike.

It is unfortunate, however, that this tradition is clearly declining. Second, all the Lithuanian folk literature books made it to the final list. Fairy tales feature very prominently and this signifies a long-running respect for our folk culture. I also have to note that poetry and literary fairy tales draw inspiration from our folk culture too.

I’d like to go back to translations now. We are very fortunate to have access to this great variety of children’s literature. It is easy to strike a conversation when travelling abroad as there is usually a book or several books that have been translated into Lithuanian. This does not, of course, mean that we don’t love or appreciate the work of our own authors. We love them and we are proud about them, in particular when they are published abroad. Kęstutis Kasparavičius and Lina Žutautė are just a few names that readily spring to mind. One special thing about Lithuania is that it has no shortage of great illustrators who chose to accompany their drawing with their own writing. It’s good you don’t have to translate illustration into other languages.