Braw Books for Bairns o Aw Ages

James Robertson

It is more than 20 years since two writers first began to discuss the possibility of setting up a Scots language imprint as part of a wider project to make Scots more audible, more visible and more accepted within the Scottish education system.

One of those writers was myself, the other was Matthew Fitt. Matthew had succeeded me as writer-in-residence at Brownsbank Cottage, the former home of the poet Hugh MacDiarmid, who had revitalised Scots as a literary language in the twentieth century. We shared a deep admiration for MacDiarmid’s work, and it was therefore appropriate that the first conversation we had about our own Scots project took place under the roof which had sheltered him for the last three decades of his life.

Whereas Matthew grew up in a Scots-speaking household in Dundee, I was born in Kent and my family only moved to Scotland when I was six. English was the language used in our house, but throughout my childhood I was always conscious of this other language going on round about me: to move house was to flit, the shopping was the messages, a light drizzle was smirr, snow was snaw, your father was your faither, your head your heid, your armpits your oxters, your toes your taes and your little finger your pinkie − and you might get a skelf in it rather than a splinter, or stave it, not jar or sprain it. There were countless words, phrases and pronunciations that distinguished the speech of people I heard in the street, on buses and in shops from my own language, and I found this both fascinating and puzzling. Years later, discovering MacDiarmid’s poetry cleared a route for me to begin to write in Scots myself. It was also key to my understanding that Scots was not just a spoken language but one with a long and rich literary history, and that the connection between the oral and the written had been severely weakened, especially in the education system.

So although we started from different places, Matthew and I both habitually used Scots in our fiction and our poetry, whether we were writing for adults or younger readers. We often worked in schools where many of the children were natural Scots speakers, but we were conscious that the provision of Scots language materials at this period (the late 1990s) was not only limited in terms of quantity and quality but was also completely haphazard. Whether Scots was read, written or studied in the classroom was entirely dependent on the enthusiasm or interest of individual teachers. As a result, most Scottish children were given only occasional access to Scots texts or – in many schools – none at all.

Furthermore, spoken use of Scots was usually systematically excluded from the classroom. Physical punishment for speaking Scots in school had ceased in the 1980s, but children were still routinely humiliated, derided or ‘corrected’ for speaking in their own tongue, and there was considerable institutional hostility to the language. Only each January, in the run-up to the annual Burns Night celebrations, were Scots texts accessed, usually for the purpose of recitation. The resources used were often well-used photocopies of single poems, by Robert Burns and others, which from their condition had little appeal to young people and from their content had little direct relevance to their lives. This led to the perverse situation that Scots, the language used to a great extent by many Scottish children in their daily lives, had no place in their formal education – except on or around the day celebrating the birth of the national bard, whose spoken and written language was Scots!

What is Scots? There has been a long and, frankly, at times quite tedious debate about this. To be absolutely clear, Scots is not Gaelic, which is an entirely distinct and separate Celtic language, whereas Scots belongs to the Germanic family of languages. Some linguists argue that it is a dialect of English, others that although it derives from the same Northumbrian Old English roots it retained or developed enough characteristics to be called a language in its own right.

If it is only a dialect, then it is certainly a remarkably strong one, since it has its own set of distinctive dialects (including for example Shetland, Doric, Glaswegian and Dundonian), a huge written and oral literature stretching back 700 years, and two multi-volume dictionaries to catalogue its vast vocabulary.

Whatever it is, it exists. A few years ago Polish academic Kasia Michalska produced a Scots–Polish Lexicon (2014). She did so after realising that many of her compatriots, arriving in Scotland under the impression that they were coming to an English-speaking country, struggled to understand not only the accents but also the vocabulary and syntax of many of the people among whom they were living and working.

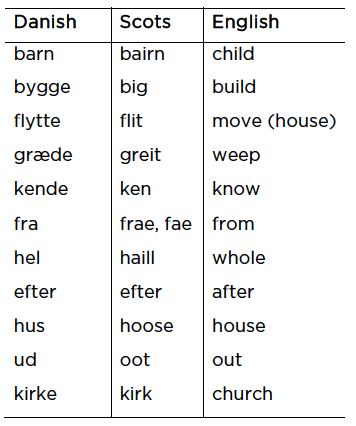

Language definition is not just a matter of linguistics, it has political and cultural dimensions too. Depending on one’s viewpoint, Scots is as close to English as Norwegian is to Danish, or as distinct from it as Catalan is from Spanish. It depends, often enough, on the strength or density of the Scots used by an individual or by the community in which they live. Like any other language, there are urban and rural varieties of Scots with different words, idioms and pronunciations. There are also many interesting connections with other European languages, as for example this table of selected Scots, Danish and English words shows:

Many Scots words come from other languages such as French (fash, to worry or make angry, from fâcher; sybie, spring onion, from ciboule), or Flemish (bucht, a sheep pen; doited, daft; and redd, to tidy up, all come from this source), imported from the continent along with people and traded goods. Gaelic, too, has given us many Scots words, such as ben, glen, loch and strath. All languages are fluid, at least until they die, and new Scots coinages keep cropping up. Most recently, for example, the long-running saga of Brexit has been aptly described as a clusterbourach.

That Scots is nowadays used in conjunction with English, and that many speakers switch from one to the other depending upon the circumstances or to whom they are speaking, is not in doubt. Nor is this surprising given the official status and strength of English in every walk of life, from education to newspapers and broadcasting. This means that not everybody refers to Scots as Scots: some people identify themselves as speakers of ‘Fife’ or ‘Hawick’, ‘slang’ or ‘bad English’. Yet when questions on Scots were asked, for the very first time, in the National Census in 2011, some 1.9 million people, or 38% of the population, said they could speak, read, write or understand Scots. This compares with about 87,000 people with similar skills in or knowledge of Gaelic. Self-identifying Scots speakers numbered 1.6 million, making Scots by some distance the second most spoken language in the whole of the UK after English.

Matthew Fitt and I believed that there was an educational need, a cultural hunger and an untapped market for books in Scots for children. Any new imprint, however, would have to compete with the many, colour-illustrated, attractively designed books in English already available to young Scottish readers. We therefore needed some serious investment to match these production values, and to establish a programme of school visits and teacher training to overturn scepticism and prejudice in the education system.

We were fortunate to have the support of Gavin Wallace, the Literature Director of the Scottish Arts Council (the predecessor of Creative Scotland). He advised us to go into partnership with an existing publisher who already had the necessary marketing, distribution and editorial expertise. We teamed up with Edinburgh-based Black & White Publishing and in 2001 successfully applied for a large National Lottery-funded grant to run a two-year programme of publishing and outreach work. In 2002 Itchy Coo published its first six titles.

The imprint logo (see top image), designed by one of our most popular illustrators, Karen Sutherland, shows a cheery black-and-white cow kicking its back legs up in the air. ‘Coo’ is an almost universally understood Scots word, but the term itchy-coo has another, subtler meaning. The online Dictionary of the Scots Language (https://dsl.ac.uk) defines it as ‘anything causing a tickling, specif. the prickly seeds of the dog-rose or the like put by children down one another’s backs’. We wanted our books to provoke just that kind of ticklish sensation, and not just among the youngest readers: our strapline was that we were making ‘braw books for bairns o aw ages’.

In those first two years we published 15 titles, some of which − such as Susan Rennie’s Animal ABC (2002) and A Wee Book o Fairy Tales (2003) by Matthew and myself − have been reprinted several times and have sold many thousands of copies. Perhaps more significantly, Itchy Coo demonstrated that there was a market for books in Scots, and that when Scots was introduced into the classroom pupils responded with recognition and enthusiasm. Since then, there has been something of a transformation, especially in primary schools, in official attitudes towards Scots. Recognising and engaging with the language that many children bring to school, rather than repressing it, encourages their linguistic curiosity and versatility, helps with inclusion and challenges the idea that their words or pronunciation have little value.

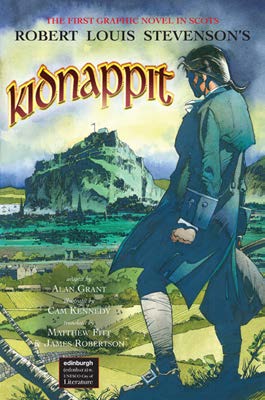

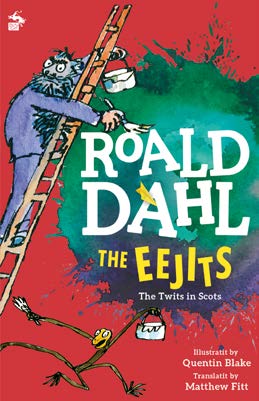

Meanwhile, beyond the school gates there was a growing demand for more books in Scots. In the 17 years of Itchy Coo’s existence we have produced more than 70 titles, including the first ever Braille book in Scots, the first ever graphic novel entirely in Scots (Kidnappit (2007), a version of Robert Louis Stevenson’s classic adventure story), a much loved series of board books and a range of books in translation. The first of these was Matthew Fitt’s The Eejits (2006), translated from Roald Dahl’s The Twits (2008). This was a huge success and has been one of our best sellers.

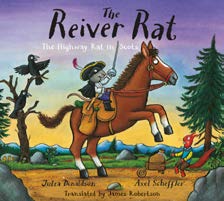

We have gone on to publish another five Dahl titles, most recently Anne Donovan’s version of Matilda (2019). Another favourite source has been the work of Julia Donaldson, who initially suggested to me that I try to translate The Gruffalo into Scots. After a couple of false starts I managed to produce a text that I felt did justice to the original, and The Gruffalo in Scots appeared in 2012. Along with The Gruffalo’s Wean (2013), The Reiver Rat (2015), Room on the Broom in Scots (2014) and others, it has sold tens of thousands of copies. We have published Diary of a Wimpy Wean (2018), Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stane (2017), Winnie-the-Pooh (2010), translations of books by David Walliams, Alexander McCall Smith, and three Asterix titles. The appetite of younger readers for reading in Scots does not seem to be diminishing. Other publishers have entered the Scots market, which was one of our objectives when we set out all those years ago – to make the publishing of books in Scots both possible and normal.

This is not to underestimate the challenges that Scots faces in a globalised world where the power and reach of English is so enormous. We have learned much from comparing and contrasting the situation of Scots with that of other ‘minority’, ‘lesser-used’ or ‘regional’ languages like Basque, Frisian and Catalan. Although Scots is recognised as a language by both the Scottish and UK governments, it does not yet have the full legal rights enjoyed by Gaelic, and its close, often intertwined relationship with English means that there will continue to be debate over its status. Nonetheless, the outlook for Scots as a published and written language is far healthier than was the case a generation ago, and so long as people continue to want to read it and write in it, and most importantly continue to speak it in all its varieties, then the shelves of our bookshops and libraries will go on being brightened by books in Scots.

Works cited

[All books published Edinburgh: Itchy Coo.]

Dahl, Roald (illus. Quentin Blake) (trans. Mathew Fitt) (2008) The Eejits: The Twits in Scots.

Dahl, Roald and Anne Donovan (illus. Quentin Blake) (2019) Matilda in Scots.

Donaldson, Julia (illus. Alex Scheffler) (trans. James Robertson) (2012) The Gruffalo in Scots.

Donaldson, Julia (illus. Alex Scheffler) (trans. James Robertson) (2013) The Gruffalo’s Wean.

Donaldson, Julia (illus. Alex Scheffler) (trans. James Robertson) (2015) The Reiver Rat: The Highway Rat in Scots.

Donaldson, Julia (illus. Alex Scheffler) (trans. James Robertson) (2014) Room on the Broom in Scots.

Kinney, Jeff (2018) Diary o a Wimpy Wean: Diary of a Wimpy Kid in Scots.

Milne, A.A. (illus. E.H. Shepard) (trans. James Robertson) (2010) The Hoose at Pooh’s Neuk.

Rennie, Susan (illus. Karen Anne Sutherland) (2002) Animal ABC.

Robertson, James (illus. Karen Anne Sutherland) (2008) Katie’s Coo: Scots Rhymes for Wee Folk.

Rowling, J.K. (trans. Matthew Fitt) (2017) Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stane (Scots language edition).

Stevenson, Robert Louis (illus. Cam Kennedy) (trans. James Robertson and Mathew Fitt) (2007) Kidnappit (The first graphic novel in Scots).

Ann Lazim is the Literature and Library Development Manager at the Centre for Literacy in Primary Education, London, www.clpe.org.uk, which holds a large collection of traditional tales retold for children. She is a member of the IBBY UK committee, a previous Chair and was co-director of the 2012 IBBY International Congress.