Black Beauty

Jane Badger

We all know Black Beauty, or at least we think we do. There are constant re-imaginings, from the 1970s television series The Adventures of Black Beauty to Disney casting Black Beauty as an American mare in the 2020 film version.

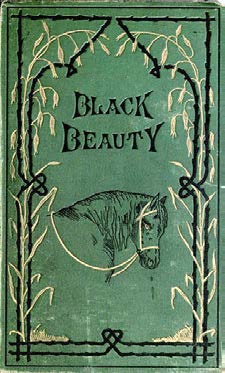

The vast majority of us will have read Black Beauty as a children’s book. My first copy was bought for me by my grandparents, who knew I loved horses. I read it, lying on my stomach on their sitting room floor, sobbing at Ginger’s fate, even though the world it depicted was one far away from mine.

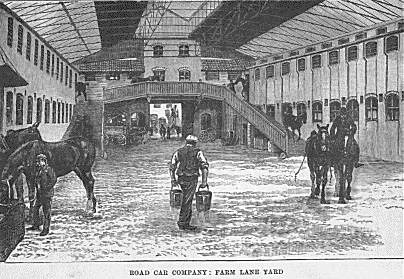

When Anna Sewell wrote Black Beauty in 1877, the horse was everything. W.J. Gordon, in The Horse World of Victorian London (1893), estimated the London horse population as 300,000. It was absolutely normal for everyone in the Victorian era to see horses all the time, everywhere. Society would have ground to a halt without the horse. Today, our world is one of the car; the horse something we never see if we live in a town. But Black Beauty is still part of our cultural life, still part of every collection of classic children’s literature.

From W.J. Gordon The Horse World of Victorian London (1893), Chapter 1. Public domain.

It is a story told by the horse himself. Black Beauty has an idyllic foalhood, and his working life starts well at Birtwick Park. But once he and the other horses are sold, their long deterioration begins, and Anna Sewell shows her readers the panoply of ways in which a horse can suffer, from the horrors of Captain as a horse of war to the miseries of cab horses in city streets. The experience of a horse having its head strapped up with a bearing rein is so vividly described that even today, when bearing reins are not generally used in the leisure horse world, everyone still knows what they are.

The book created a revolution in the way the horse was treated. In 1886, Alfred Saunders in Our Horses, wrote that ‘Bearing-reins are less used every year. Miss Sewell’s Black Beauty and the energetic appeals and well told facts of Mr. and Mrs. Flower on this subject have done wonders.’ The RSPCA added its endorsement to the 1894 reprint of Black Beauty.

Black Beauty’s influence spread well beyond Britain. Her book (shamelessly pirated by George T. Angell: neither Anna Sewell nor her family saw one penny of its mighty sales in America) was distributed free to drivers and stablemen in the United States. Angell wrote:

Under Divine Providence, the sending of this book, Black Beauty, into every American home may be . . . an important step in the progress not only of the American, but the World’s humanity and civilization.

Anna Sewell put herself into the head of the horse and wrote directly about how they experienced life in the Victorian horse world. In doing so, she created a minor revolution in the world of equine literature. At first sight, her book fitted neatly into an already existing vein of didactic children’s literature concerned with animals. The Memoirs of Dick the Little Poney, published in 1800, make it quite clear why the book was written, when Dick says:

. . . and if my strictures tend to procure more uniform favour to my kind . . . I shall not regret that I have written, nor shall my history be read without improvement.

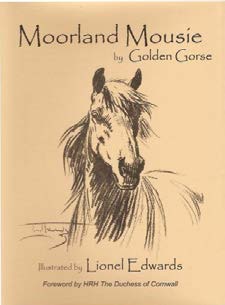

But Black Beauty took off and had a resonance with its reading public that Dick and its fellows never achieved. It became the model for children’s equine literature for a good 50 years after it was published. Title after title appeared in which the horse or pony told its own story: Trusty, Our New Forest Pony (1905), The Don and the Dancer (1907), Moorland Mousie (1929), and many others until, with the disappearance of the working horse, stories focusing on the child rather than the pony took over in the 1930s.

Black Beauty, almost alone, has survived, while its imitators have fallen by the wayside. Amongst all those other pony autobiographies, there is none, apart from Moorland Mousie, that is still in print.

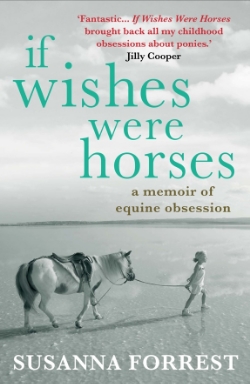

Susanna Forrest, in If Wishes Were Horses (2012), learned about the cruelties visited on horses as a child listening to Black Beauty on cassette tapes, narrated by Angela Rippon, bought by her parents to keep her quiet on long car journeys. ‘Into my ears,’ she wrote,

poured sufferings more vivid than any fairy tale . . . Horses, I learned, could not save themselves from abusive humans, but must be rescued from these horrors by other, more compassionate humans. I needed to be better than Jakes and the grand lady at Earlshall, and to be the one that saved Ginger and Beauty over and over again.

Although I have read a great many pony autobiographies, none takes hold of me in the way that Black Beauty continues to. I know the plot backwards, but still I turn the pages, still I am immersed in every disaster, in every triumph. I read it differently now, because I am 50 years older than when I wept for Ginger on the sitting room floor. Now I can see how wide its reach is, from the top to the bottom of society, and I can see how age is no bar to behaving badly, or well.

What I felt, and feel, an immediate sympathy for, is the horse. I feel for his powerlessness, see his pride in his job done well, and learn with him as he travels through life. Put like that, the book ought to be a didactic disaster, but it is not. Anna Sewell manages to cloak a horse in humanity, while never losing sight of the fact he is a horse, and he suffers, and experiences, what horses do. Anna Sewell succeeded in getting inside the head of a horse in a way that is recognisable to those who know horses, and of instant appeal to those who have never met a horse in their lives. It resonates still with both adults and children.

All its readers for over 150 years have learned what the lady who must surely be speaking for Anna Sewell herself, says as she steps forward to advise the carter to loosen off the bearing rein:

. . . we have no right to distress any of God’s creatures without a very good reason; we call them dumb animals, and so they are, for they cannot tell us how they feel, but they do not suffer less because they have no words.

Works cited

Anon (1800) The Memoirs of Dick the Little Poney. London: Whittingham & Arliss, Juvenile Library.

Avis, Ashley (2020) Film based on Black Beauty by Anna Sewell. Directed by Ashley Avis. Produced by Jeremy Bolt and Robert Kulzer. Distributed by Disney.

Buckland, Mary E. (1905) Trusty, Our New Forest Pony. London; Edinburgh: R.B. Johnson.

Forrest, Susanna (2012) If Wishes Were Horses : A Memoir of Equine Obsession. London: Atlantic.

Golden Gorse (illus. Lionel Edwards) (1929) Moorland Mousie. London: Country Life.

Gordon, W.J. (1893) The Horse World of Victorian London. London: The Religious Tract Society.

Saunders, Alfred (1886) Our Horses or the Best Muscles Controlled by the Best Brains. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington.

Scrimgeour, Maud (1907) The Don and the Dancer. London: Thomas Nelson.

Sewell, Anna (1877) Black Beauty. London: Jarrold and Sons.

Willis, Ted, Richard Carpenter and David Butler (1972–1974) The Adventures of Black Beauty. TV Series. Directed by Charles Crichton, Peter Duffell and John Reardon. Executive Producer: Paul Knight. Producer: Sydney Cole.

Jane Badger is the author of Heroines on Horseback: The Pony Book in Children’s Literature, and writes on women and the horse. She is the founder of Jane Badger Books, which brings classic children’s equine fiction back into print.