A Therapeutic Ogre

Beth Webb

I was thrilled to be invited to talk about fairy stories as family therapy at IBBY UK/NCRCL MA’s ‘Happily Ever After’ conference in November 2017. But instead of giving a paper in the normal way, I turned my ideas into a brand-new fairy story – ‘The Ogre’s Wood’ – and told it.

‘Pure mischief,’ I replied. ‘This was a conference on the future of fairy tales; I’m a professional storyteller as well as a children’s author, so it seemed a logical thing to do. I think I was also daring myself to see if I could do it.’

But more seriously, it was also a way of testing several areas of my talk’s hypotheses:

- Storytelling helps us take one step away from reality to make sense of and manage the chaos of real life. (A synopsis of the story will be on the new IBBY UK website when the transfer has been completed from the old website.)

- But this is a perilous adventure; grown-ups and children need each other’s experiences and perspectives to find the way through their own ‘Ogre’s Wood’.

(a) Children need to read fairy stories with a trusted adult (nearby) to teach them essential life-skills: dragon taming and maze negotiation, etc., and also to reassure them and bring them back to reality when the stories get too scary. (b) Fairyland is rarely finished with grown-ups. Sadly, we often forget this. Reading with children takes grown-ups back to fairyland, where, if we keep our minds and hearts open, we may just find treasure maps for our tangled lives.

If I could make some of these ideas work as a told story, I’d demonstrate the strength of storytelling both as communication and a therapeutic tool. I also hoped to take my listening adults on a trip back to fairyland!

I based the thinking for ‘The Ogre’s Wood’ on the work of my friend Patricia Stewart, a clinical psychologist with many years of expertise in the field of child and family therapy (Patricia Stewart BA (Hons), MA (Child Psychology), C.Psychol., AFBPsS, HCPC Registered Clinical Psychologist, EMDR Therapist). She uses both traditional and bespoke made-up stories to help her clients make sense of what is happening to them.

Some very traditional storytellers may be shocked at the thought of adjusting ancient stories to the needs and interests of the listeners, but both Patricia and I believe this is a vital part of the process. After all, stories are mirrors of humanity’s thoughts and experiences. As our culture and circumstances change, so must our tales.

Of course, it’s important to treasure a dramatic recording of an immortal tale, but stories are like babies. They have to grow up. They long to travel. They will come home different, maybe with a foreign partner who needs to be loved, into our family narrative. In return, our changed child and their sweetheart will enrich us with their new stories.

We change. The world changes. Stories change. Even archetypes change.

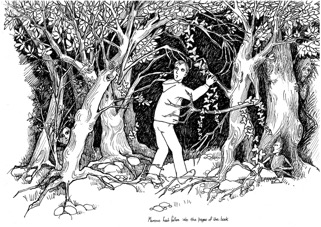

In ‘The Ogre’s Wood’ the main character identifies as ‘the Witch’ and the listener is uncertain whether she’s planning to cook and eat her young visitor (Marcus), or to save his life. I tried to keep this uncertainly dangling as long as possible, while the Witch examines her own narrative. Deep inside, she’s scared she’ll accidentally put Marcus, not the roast, into her nice hot oven (i.e. damage him) because that’s what witches and step-mothers do. This is because she’s allowed ossified archetypes, fear and doubt to determine her life. She has allowed the Ogre’s Wood to grow right up to her cottage walls. There’s no escape unless she can learn that stories provide the tools to take creative ownership of her present and her future.

When Marcus gets lost in the Ogre’s Wood, the Witch knows only that she can save him, but dare she? Fairyland’s shadows still terrify her.

In the end, the Witch discovers that the love and trust she and Marcus share is magic enough to see them through all the mistakes to come. With this mere ‘twig’ of a magic wand, she cannot only dispel the shadows from her own childhood, but also help Marcus through his.

Similarly, Marcus helps the Witch name and use the shadowy figure lurking by the hollow oak in her nightmares. Once this is achieved, she and Marcus take ownership of the Ogre’s Wood together, and the prospect of becoming Marcus’ step-mum becomes a joy, not a terror.

In this way, traditional story archetypes (all witches are evil, all shadows are to be feared) become useful starting points – but the listener needs to examine these, questioning their aims and motivations, then to look for, or even demand, change. This is a two-way process: the listener must learn to become a story-maker, manipulating the tale, but they must also allow the characters to live, acting out new stories so they can try out the fresh ideas; see what works, what doesn’t – and why. This process becomes a safe dummy run for reality.

If a storyteller (rather than a book) is involved, they must give up all ownership of the tale, allowing the listener to become a story-maker. They can then recreate the story as they need it to be, whether it’s assigning new roles to the characters, or acting out an updated version of the tale. This allows the story-maker to put names and faces to their dreams and nightmares, but in difficult situations, it’s very important to work with a trained counsellor or therapist. (You can find a good therapist at https://www.psychotherapy.org.uk/find-a-therapist/, https://www.counselling-directory.org.uk and https://www1.bps.org.uk/bpslegacy/dcp.)

So far, I’ve applied my comments to adults. Obviously, everything applies equally to children. As a storyteller, I’m horrified that people assume stories are for kiddies. As I’ve said before, adults are never finished with fairy tales, and fairy tales have rarely finished with us. Throughout our lives, archetypes still ferret away in our subconscious, trying to make sense out of the grief and chaos. The adult addiction to books and films like ‘The Game of Thrones’, ‘Lord of the Rings’, and even ‘James Bond’, as well as fantasy computer games and cosplay, all point to this. Adults without stories find the world a difficult and lonely place.

Quick questions:

- Which fantasy character do you identify with?

- Now ask yourself why. Write it down and think about.

- What does that say about you?

OK, this approach doesn’t work for everyone; some people just don’t ‘get’ stories, thank goodness we’re all different. However, this approach to coping can be a lifesaver. But be warned, whether told or read, the story-tale world of the imagination can become dangerously real, a place where it’s perfectly possible to become lost and face real danger – as happened to Marcus. This is why children need a loving adult nearby to read their eyes and body language, keeping them in a safe place, reminding the child, ‘Don’t worry, it’s only a story. We’ll all come safely home at the end – even if ‘home’ isn’t where you thought it was, and it’s a nurturing wolf, not a granny who’ll care for you.’

If you make time to read with a child, you’ll also improve their literacy skills and give you both happy memories.

Let’s look at how stories work. Essentially, a strong metaphor that is told and explored (whether written, drawn, told or danced, it doesn’t matter, it’s all storytelling) becomes a way of experiencing difficult things vicariously.

A child reads ‘Red Riding Hood’ and can then discuss with their grown-ups how to deal with strangers who want to know where they’re going and what they’re doing. This works as a sort of dress rehearsal in the mind, so when that young person does meet someone who’s asking too many questions, or offering unwanted attention, they’ve already rehearsed what to do and say. They aren’t thrown off balance. They cope much better with keeping themselves safe.

Again, the metaphor is essential here. A direct story about a hairy man approaching a girl in a red hoodie at the bus stop on the way to Grandma’s, could be terrifying for a sensitive child. Similarly, children are often given pets to help them learn how to care – and more importantly, how to cope with life and death – although it doesn’t always work. A friend of mine gave a hamster to her children with exactly this in mind. While this lady was away on business, the hamster died. The kind friend who’d been looking after her children, phoned my friend to tell her about the hamster’s demise. ‘Don’t worry,’ she said cheerfully, ‘I’ve got an identical replacement, the children will never know Hammy snuffed it.’

Revisiting the tales from an adult perspective enables us to take on different personas within the tale. The character we’d have identified with as a child, or even five years ago, may be very different from the name you wrote down in response to my first question above.

As adults, we need to allow that process to help us understand ourselves, whatever our age. For adults to read, or even better create, stories with children, as Marcus and the Witch did, enables us to find our prince/ss in shining armour, to kiss the frog we’ve ignored and feared for years, or to take ownership of the spooky wood outside the front gate of our minds. The child’s perspective may help us see things in a way we’d forgotten.

Do try story making with your children or grandchildren. It may prove to be a way to talk about things that both of you have found unsayable for a long time. You don’t have to be brilliant at creative writing, you need only to love stories – and the young person you’re talking to. (And personally, I’d prefer to say all that in a good story rather than deliver an academic paper – if I can possibly get away with it.)

Addendum

This addendum is by Patricia Stewart whose vast experience with children, young people and their families gave me the ideas and the psychological theory for ‘The Ogre’s Wood’. She says: ‘My inspiration for narrative therapy comes from traditional stories, but I am deeply grateful to quite a few writers from a wide variety of backgrounds for their thoughts and insights in how to actually use the stories.’

A people are as healthy and confident as the stories they tell themselves. Sick storytellers can make nations sick. Without stories we would go mad. Life would lose its moorings or orientation … Stories can conquer fear, you know. They can make the heart larger. (A Way of Being Free by Ben Okri)

The earliest storytellers were magi, seers, bards, griots, shamans. They were, it would seem, as old as time, and as terrifying to gaze upon as the mysteries with which they wrestled. They wrestled with mysteries and transformed them into myths which coded the world and helped the community to live through one more darkness, with eyes wide open and hearts set alight. (A Way of Being Free by Ben Okri)

Like the shaman, the storyteller is a walker between the worlds … someone who communes with dragons … able to pass freely from this world into non-ordinary reality and to help us experience those other realms for ourselves. (The Shaman and the Storyteller by Michael Berman)

From the ancient stories of the Prophets, to the parables of the New Testament, from the Nordic tales to medieval romance and modern TV soaps, humans and their children have used stories and storytelling to make sense of their worlds.

We think and speak in metaphor, we tell tales and bear witness to our lives. The person without a story, who has lost their autobiography, is someone who has fundamentally lost their identity and meaning. There is less than a breath between the ‘Once upon a time there was’ to the therapist asking ‘tell me what happened’, and then the tales unfold; loss and hope, dreams and betrayals, grief and courage, all there.

The therapist can consciously access these dreamtimes, these tales and archetypes to co-construct new possibilities of hope and survival, and a possibility that they can together find the lights in the darkness.

Rather than psychotherapy texts , I set my students to read JohnConnelly’s The Book of Lost Things, a fantasy novel that takes a fresh look at traditional fairy tales, following a child’s journey into adulthood. But perhaps the all-round human need for stories is best summed up by Philip Pullman: ‘After nourishment, shelter and companionship, stories are the thing we need most in the world.’ (From an interview for Scholastic Kids Club athttps://clubs-kids.scholastic.co.uk/clubs_content/7922.)

References

A Book of Lost Things: John Connelly (Hodder 2007).

Out of the Wreckage: George Monbiot (Verso 2017).

Coming Home to Story:Geoff Mead (Jessica Kingsley2013). Originally published 2011 Vala Publications.

A Way of Being Free: Ben Okri (Head of Zeus 2014).

The Shaman and the Storyteller: Michael Berman (Superscript 2005).

Poetry and Story Therapy: Geri Giebel Chavis (Jessica Kingley 2011).

For help with the story-making process, have a look at my ‘Advice to Writers’ pages: https://www.bethwebb.co.uk/advice-for-writers. If you or your child is in therapy, it’s worth discussing story making with the therapist and getting some guidance.

Further references

The Psychology of Storytelling: https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/habits-not-hacks/201411/the-psychology-storytelling.

The Art and Science of Storytelling Therapy: http://storytellingtherapy.com/. The purpose of this website is to inform and educate the reader about storytelling therapy; a powerful, fun and exciting method of psychotherapy.

Everybody has a Story: The Role of Storytelling in Therapy: blog.oup.com/2014/01/therapeutic-storytellingby Johanna Slivinske. When was the last time you told or heard a good story? Was it happy, sad, or funny? Was it meaningful? What message did the story convey?

Books that cross the divide

What to Do when you Worry too Much: Dawn Huebner (Magination Press 2005).

The Boy and the Cloth of Dreams: Jenny Koralek (Walker Books 1995).