A Native Scholar’s Perspective on the Caldecott Medal

Dr Debbie Reese

On 25 January, near the end of the livestream of the 2021 Youth Media Awards, Kirby McCurtis, President of the Association for Library Service to Children said:

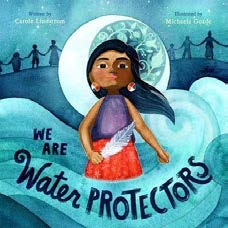

The winner of this year’s Randolph Caldecott Medal for outstanding illustration of a children’s book is ‘We Are Water Protectors’, illustrated by Michaela Goade, written by Carole Lindstrom, and published by Roaring Book Press, a division of Holtzbrinck Publishing Holdings.

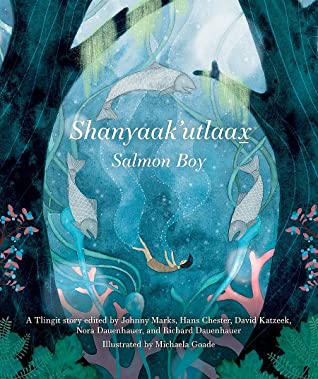

Across social media, there was a joyful chorus as Native people learned the news. In 2017 Goade did the illustrations for Shanyaak’utlaax: Salmon Boy, a traditional Tlingit story edited by Johnny Marks, Hans Chester, David Katzeek, Nora Dauenhauer and Richard Dauenhauer. That book won the American Indian Library Association’s Youth Literature Award in the Picture Book category in 2018.

With the Caldecott news, Native reporters for Native news media jumped on the story. The Central Council of Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska tweeted:

Congratulations to tribal citizen Michaela Goade for becoming the first Native American to win the Randolph Caldecott Medal.

In October of 2019 I saw a galley for We Are Water Protectors. Written by Carole Lindstrom (Turtle Mountain Chippewa) and illustrated by Michaela Goade (Tlingit, member of the Kiks.ådi Clan), I thought that Goade’s art was stunning. I was certain it would be a strong contender for the 2021 Caldecott Medal.

I was – and am – a voice in that chorus but I am also a scholar of children’s literature. I knew she was the first ever Native woman to win the award. And while I celebrated with Native people across what some tribal peoples call Turtle Island (the North American continent), I was also aware of a sense of injustice that – with this brief essay – I hope to describe.

Every non-Native writer, illustrator, editor and publisher that is living and working on the continent known as North America is on land that is, or once was, Indigenous land. Though people think we were primitive and that we no longer exist, the fact is our ancestors met invasions of homelands with resistance and then, diplomacy. They are the reason Native people are here, today. Their fight for our status as sovereign nations is why the Central Council of Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska used the words ‘tribal citizen’.

For thousands of years, Native people have created art. Museums around the world have items in them that were taken from us and today, leaders of Native Nations have been working hard to get those items returned. My point: we’ve been creating desirable art for a very long time. And yet, a Native artist has never won the Newbery.

Hopefully we agree it is not due to a lack of talent or artistic gifts. In the 1990s when I started working in children’s literature as a scholar, I heard many editors say that Native people did not submit stories or art to them. It felt like an ‘it isn’t my fault we don’t publish books written or illustrated by Native people’ defense rather than a proactive ‘what can we do to change that’.

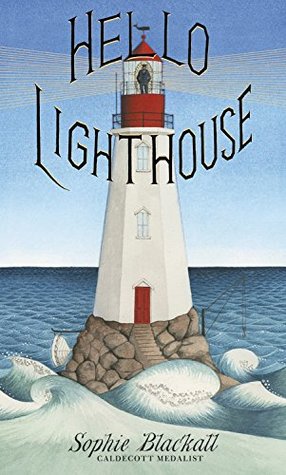

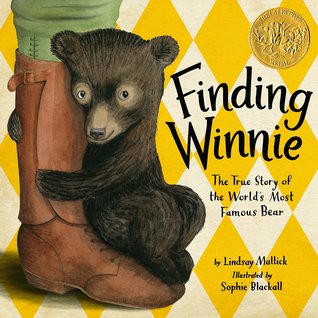

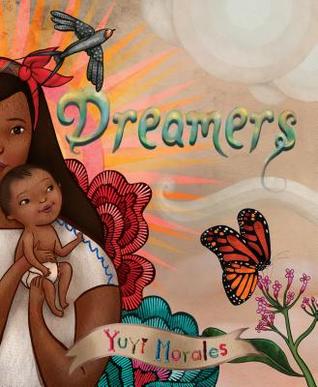

One thing that needs to change is the whiteness of children’s literature. In 2019, Sophie Blackall won the Caldecott for Hello Lighthouse. That was her second win. She won it in 2016 for Finding Winnie: The True Story of the World’s Most Famous Bear. Her work is fine but does it merit two wins within such a short period of time – a time when children’s literature is exponentially growing with respect to the diversity in who gets published? I don’t think it does. That was the same year that Yuyi Morales’s exquisite book, Dreamers, came out. Nobody will ever be able to persuade me that the Hello Lighthouse is superior to Dreamers. It isn’t.

If Dreamers had won the Caldecott in 2019, it would have been the first win by a not-white woman. It didn’t, and so here we are in 2021, celebrating Michaela Goade as the first not-white woman to win the medal. Are you surprised by that information? I was, initially. That day, The Horn Book tweeted that fact. A day later on their Calling Caldecott web page, Martha V. Parravano and Julie Danielson wrote

She is the first non-white woman, the first Indigenous woman, the first BIPOC woman to win – there are lots of ways to put it. All are true, and all are ground-breaking.

As you page through We Are Water Protectors, take time to study Goade’s illustrations of people. The book is Native, through and through. Carole Lindstrom wrote about Native people who are standing up to protect vital resources. We Are Water Protectors is about Native people saying no to oil companies that seek to dig trenches to lay pipelines – in some cases, disturbing sacred burial sites – and to install pipes that can burst and put drinking water at risk. This is a story of Native resistance in the present day, written and told by Native women.

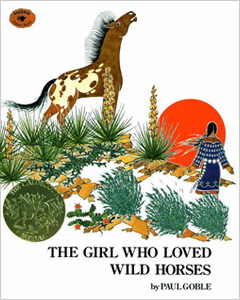

As you think about the books that have won the Caldecott in previous years, some of you might be thinking about Paul Goble’s The Girl Who Loved Wild Horses. It won in 1979. In an interview he stated his style was influenced by the ledger book. That particular art was created by Plains men incarcerated at Fort Marion in Saint Augustine, Florida, in the 1870s. I don’t know if, in 1979, anyone accused Goble of appropriating a Native art style, but we would not hesitate to say that, now. Some people think it is a traditional Native story, but it is his own creation. That sort of thing comes under more criticism now than in the past.

In a nutshell, a not-Native man (Paul Goble) appropriated a Native style of art and made up a story that he puts forth as being Native. Let’s juxtapose that with We Are Water Protectors. Two Native women (Lindstrom and Goade) created a story about Native resistance to exploitation. Quite a difference, isn’t it?

As you study the people in We Are Water Protectors, you’ll see Native people – young and old – in traditional clothing they’ve chosen to wear at gatherings, but you’ll also see many in everyday wear like jeans and sweaters and hoodies. On the final page you will see a range of appearance. Some Native people have dark skin; some have light skin. Physical appearance is not what makes someone Native (or not). It is citizenship in a tribal nation. There’s so much to know about us! I hope We Are Water Protectors intrigues you into learning who we are – for real. There’s been far too much Goble-like material created about us. It is long past time that people learn about us, from us.

Works cited

Blackall, Sophie (2018) Hello Lighthouse. New York: Little, Brown & Co.

Goble, Paul (1978) The Girl Who Loved Wild Horses. New York: Bradbury Press.

Lindstrom, Carole (illus. Michaela Goade) (2020) We Are Water Protectors. New York: Roaring Brook Press.

Marks, Johnny, Hans Chester, David Katzeek, Nora Dauenhauer and Richard Dauenhauer (eds) (illus. Michaela Goade_ (2017) Shanyaak’utlaax: Salmon Boy. Juneau, Alaska: Sealaska Heritage Institute. (Update of the 2004 edition published by Sealaska Heritage Institute.)

Mattick, Lindsay (illus. Sophie Blackall) (2015) Finding Winnie: The True Story of the World’s Most Famous Bear. New York: Little, Brown & Co.

Morales, Yuyi (2018) Dreamers. New York: Neal Porter Books.

Websites

Parravano, Martha V. and Julie Danielson (2021) Calling Caldecott: Momentous History Made!. 26 January 2021. https://www.hbook.com/?detailStory=momentous-history-made.

Facebook livecast of 2021 Youth Media Awards: https://www.facebook.com/watch/live/?v=119572856701439&ref=watch_permalink.

Paul Goble. (Obituary and April 20, 2014 interview) at Wisdom Tales: http://www.wisdomtalespress.com/authors_artists-childrens/Paul_Goble.shtml.

Central Council of Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska, Twitter: https://twitter.com/tlingithaida/status/1353900492183773184.

Tribally enrolled at Nambé Pueblo (a sovereign Native Nation in what is currently the United States), Dr Debbie Reese is the founder of American Indians in Children’s Literature. Her book chapters, journal, and magazine articles are taught in English, Education and Library Science courses in the United States and Canada.