Exhibition Review: Alice: Curiouser and Curiouser

Exhibition Details

An ‘immersive and mind-bending journey down the rabbit hole’ The Sainsbury Gallery at the Victoria & Albert Museum, Cromwell Road, South Kensington, London SW72RL. Saturday 22 May 2021 – Friday 31 December 2021. https://www.vam.ac.uk/exhibitions/alice-curiouser-and-curiouser.

June Hopper Swain

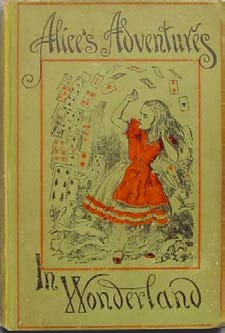

Designed by award-winning Tom Piper, this ambitious and well worth waiting for exhibition delayed by 14 months due to the Covid-19 pandemic lockdowns, celebrates 157 years since Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) by Lewis Carroll was published.

From his original handwritten Wonderland manuscript (1864) to stage costumes, digital projections and interactive displays, the Pop Culture of the 1960s and 1970s, the Surrealists and the Psychedelic artists to Alice branding, like the Victorian biscuit tins on display, the cultural impact of Alice and its sequel Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There (1871), both texts never being out of print, is fully explored and reveals the ways that it invites originality in many forms.

The immersive descent into the V&A’s below ground level Sainsbury Gallery represents the rabbit hole down which Alice tumbles after she falls asleep. At the bottom, visitors can learn about Alice’s inception in Victorian Oxford where Lewis Carroll, pseudonym of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (1832–1898) was a mathematics lecturer and ordained deacon in the Church of England. A photograph (1872) on display of the real Alice Liddell (1852–1934), a self-confident looking, firm-jawed 20 year old, was taken by the great Victorian photographer Julia Margaret Cameron (1815–1879). Dodgson, an accomplished amateur photographer took several pictures, as we see, of Alice as a child.

Playfulness is a key element in this exhibition that reflects Dodgson’s enjoyment in wordplay and games, and logic puzzles. Many of the characters in Wonderland are playing cards, while some of those in Looking-Glass are chess-set pieces, their moves, more or less, ‘following the laws of the game’ (1911: ix) and both are populated by characters, some anthropomorphic, intent on wrong-footing Alice with their puns and abrupt changes of subject. Dodgson enjoyed parodying the then well-known didactic poems and songs for children that, together with excerpts from the stories, as we hear, are fun read aloud. There are amusing hands-on devices too, such as the contraption that lengthens Alice’s neck (seen in Tenniel’s illustration, 1928: 15), when the handle is turned.

Dodgson first met Alice, aged four, in Oxford where her father was Dean of Christ’s Church, and this exhibition recalls that ‘golden afternoon’ some six years later on the river when Dodgson told Alice the story of her namesake’s adventures. On display is the handwritten manuscript, bound and presented to her by Dodgson called Alice’s Adventures Under Ground (1864), featuring his charming but rather naïve drawings. Dodgson’s poem ‘All in the Golden Afternoon’ first appeared as the preface to the extended story retitled Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) with Dodgson’s drawings replaced, with his consent, by those of illustrator and political cartoonist John Tenniel (1820–1914), all of which are on display together with processes used to print them.

This is both an entertaining and informative exhibition that places Dodgson’s stories within the context of the times in which they were written. We are reminded, for instance, of the ways the stories reflect technological advances while the evolutionary theories propounded by British-born geologist and naturalist Charles Darwin (1809–1882) in The Origin of Species (1859) was a particular influence. The first version of Wonderland was completed five years after Darwin’s publication, and we see the concept of change and the relativity of things in Alice’s frequent changes in size, while characters in both Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass make her question her very existence. In the latter, for instance, in which Alice learns to cope with ‘the effects of living backwards’ (1911: 95), there is the terrifying prospect of being snuffed out like a candle (1911: 81–82). The old certainties of religion and the physical world were being questioned, although, satisfyingly, Alice’s own self-belief – she is surely a proto feminist – always wins through.

Referencing the Darwinian theory of the ‘survival of the fittest’, and particularly poignant, is the skeleton on display of a dodo, an ungainly, flightless bird, extinct by the end of the seventeenth century, but happily immortalised in Wonderland as an anthropomorphised character in the chapter ‘A Caucus-Race and a Long Tale’ (1928: 30–42). In the same display case, we are reminded, via a model steam railway engine, of the development of railway travel in the Victorian era that meant that many people were becoming more mobile, including Alice who takes an eventful train journey in Looking-Glass (1911: 49–55).

Also on display are some very individual takes on Wonderland that may challenge those who see Tenniel’s illustrations as definitive. They do, however, provide us with fresh, exciting perspectives. There is Spanish-born Surrealist (1904–1989) Salvador Dali’s hauntingly beautiful imagery with its disconnected and spacious landscapes vibrantly coloured as in A Mad Tea Party (1969), and there is Welsh author and illustrator (b. 1936) Ralph Steadman’s original scratchy pen-and-ink drawings, like the depiction of a manic, pot-bellied, bowler hatted White Rabbit (1967). An eye-catching psychedelic poster (1967) by American abstract artist Joseph McHugh (b. 1939), featuring in capital letters the quote WE’RE ALL MAD (1911: 93), shows the Cheshire Cat, here represented by a photograph of an impressive black, long-haired puss, not a bit anthropomorphic in appearance, wearing an enigmatic smile rather than a grin, unlike Tenniel’s maniacal feline (1928: 92), and with a disconcerting stare from eyes that have blood red pupils. This, against a jazzy, eye-dazzling background, suggests the giddiness that the cat’s appearing and disappearing habit has on Alice (1928: 95).

Alice has been filmed several times during the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. On display is American artist, animator and designer Mary Blair’s original artwork and storyboards for Walt Disney’s 1951 animated film Alice in Wonderland, that is also screened at the exhibition, and there is a British 1903 silent version of Alice using a cast of actors and camera trickery, a curiosity not without charm, partly restored and held by the British Film Institute (BFI). Also featured is American Tim Burton’s 2010 reimagining, with actors and visual effects, of the story with Alice, now a 19 year old, reunited with some of the Wonderland and Looking-Glass characters, and, among other costumes displayed, is cast member Johnny Depp’s splendid Mad Hatter outfit designed by Oscar winner Colleen Atwood (b. 1948).

The use of digital interactive projections transport the visitor to some of the settings of Alice’s various encounters. Perhaps the most ingenious and graphically satisfying is the interpretation of The Pool of Tears in Wonderland (1928: 15–29) with the words of the text, representing Alice’s tears, falling from the pages into a ‘pool’. Elsewhere, distorting mirrors and a floor made up of receding black and white squares, ‘just like a large chess-board’ (1911: 38), combine to create a dazzling, disorientating effect to cleverly suggest something of Alice’s own feelings in Looking-Glass (1911: 95). It was for this story that Tenniel created Alice’s ‘iconic and much imitated look’ of the stripy stockings and the ‘Alice’ hairband.

From the Victorian era onwards, Alice in Wonderland has been staged many times, one of several production posters on display advertising a dramatised version as ‘a musical dream play’ (1886) at The Prince of Wales Theatre, London, while in the twenty-first century we see the innovative ways that dance, including ballet, has adapted Dodgson’s story. From fashion design and photography, that echo the exhibition’s phantasmagorical theme, to a film about ALICE (A Large Ion Collider Experiment) at CERN, the European Organisation for Nuclear Research, describing the function of the underground laboratory, sometimes called a ‘rabbit hole’, for exploring the physics of matter, all demonstrate the phenomenal influence that Alice continues to have. This innovative exhibition will surely inspire children and grown-ups alike to reread, or perhaps read for the first time, Dodgson’s stories that are a fundamental part of our British literary heritage and far beyond.

A lavishly illustrated hardback book: Alice: Curiouser and Curiouser, published by the V&A, is available at £35.

Acknowledgements

Black-and-white illustrations by John Tenniel for Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Charles Dodgson/Lewis Carroll (1865). These images are in the public domain.

Works cited

Carroll, L. (illus. Lewis Carroll) (1864) Alice’s Adventures Underground. Oxford: bound original handwritten manuscript (held by The British Library, London).

–– (illus. John Tenniel) (1865, 1928) Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. London: MacMillan.

–– (illus. John Tenniel) (1871, 1911) Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There. London: MacMillan.

–– (illus. Ralph Steadman) (1967) Alice in Wonderland. London: Frank Dobson.

–– (illus. with a woodcut and etchings by Salvador Dali) (1969) Alice in Wonderland. Limited Edition. New York: Maecenas Press.

Darwin, C. (1859) On the Origin of Species by means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life. London: John Murray.

Sladen. S. and K. Bailey (eds) (illus. John Tenniel and others) (2020) Alice: Curious and Curiouser. London: Victoria and Albert Museum.

Websites

The first film adaptation of Alice in Wonderland (1903) produced and directed in Britain by Percy Stow and Cecil Hepworth, uploaded by the BFI 2016: https://www.openculture.com/2016/03/the-earliest-film-adaptation-of-alice-in-wonderland-from-1903.html.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Tenniel Illustrations for Alice inWonderland, by Sir John Tenniel: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/114/114-h/114-h.htm.